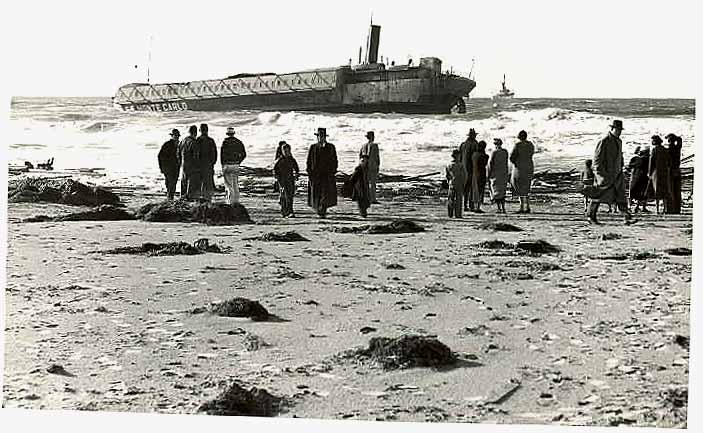

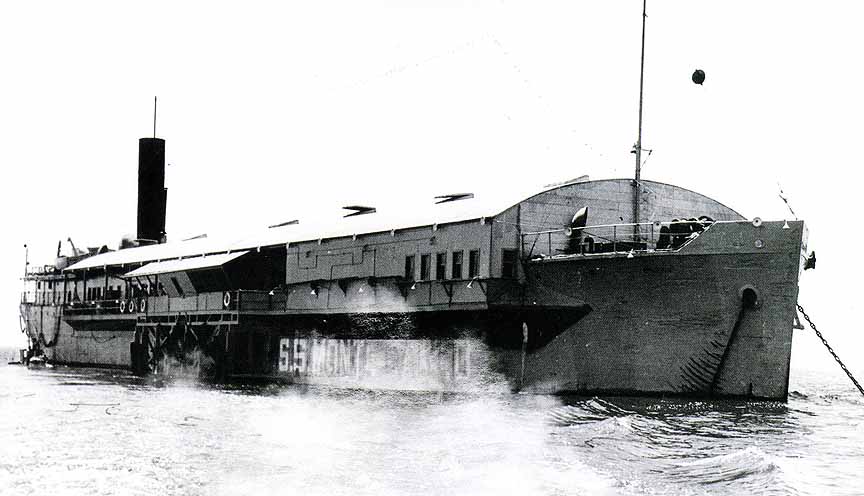

In her prime, the S.S. Monte Carlo was the largest of a fleet of ships making up Gambling Ship Row that dotted the map between San Diego, Long Beach and Santa Monica. Photo courtesy Ernest Marquez.

MYSTERY OF SHIPWRECK MONTE CARLO

CONTINUES TO UNFOLD

By Joe Ditler

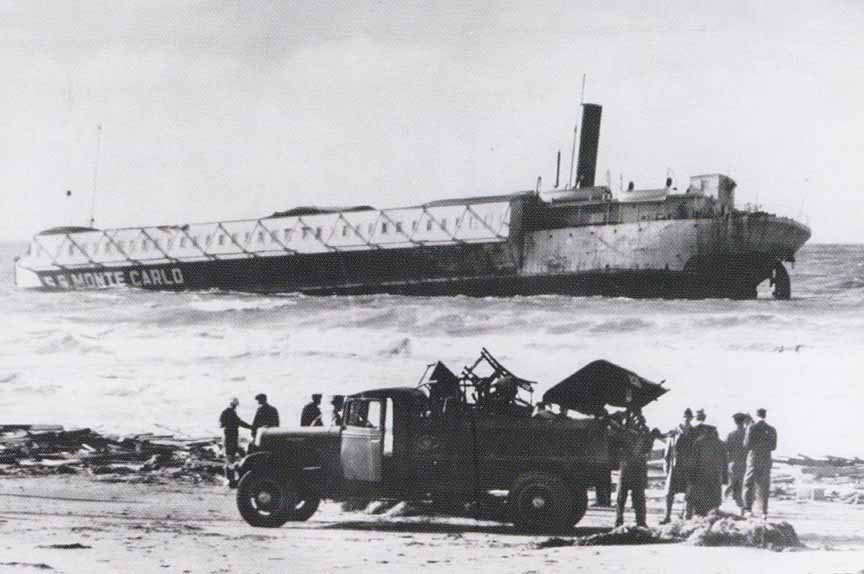

This photo was taken by a photographer from the San Diego Union. It is early on the morning of January 1, 1937. The Coast Guard cutter, Itasca, can be seen steaming away after successfully removing the two caretakers from the doomed, floating gambling casino as residents from Tent City wait for the sea to toss up more rewards. Photo courtesy Coronado Public Library.

CORONADO – While the rest of the world was partying New Year’s Eve, 1936, a heavily laden gambling ship tore at her moorings three miles offshore, victim of a vicious winter storm. On board were all the accouterments to party booze, gambling machines, mirrored ceiling but the only signs of life were two caretakers. And it was all they could do to just hunker down and ride out the storm.

Early on January 1, 1937, the 300-foot “sin ship” the floating gambling casino Monte Carlo broke the massive mooring chains that had secured her to the ocean bottom. First the bow chain parted, then the stern. Helplessly, she was at the fate of wind and tide.

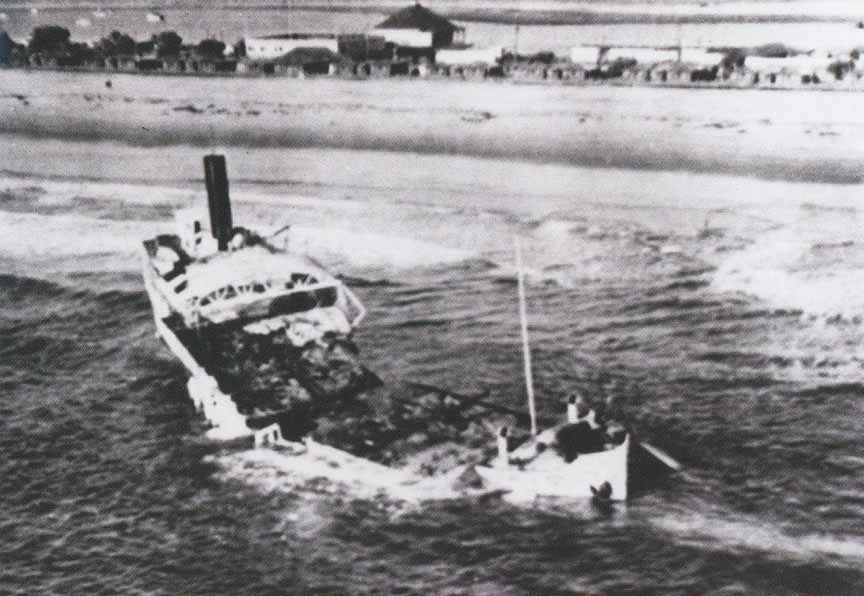

Monte Carlo lay on her side, as she was launched on her side. With each passing storm more of her would wash up on the beach until eventually only her cement superstructure could be seen. Atop Point Loma the only structure is the lone Cabrillo Lighthouse. Photo courtesy Coronado Public Library.

Through the dark and stormy night Monte Carlo sailed on, eventually running hard aground on Coronado’s Tent City Beach at the break of day. This harrowing shipwreck tale has become one of Coronado’s greatest legends, and a mystery that has defied time. Today, many Coronado residents know nothing of the story. Visitors walk the beach describing the wreckage as everything from a Japanese submarine to a pirate ship. In 2005 a local writer/historian named the beach, “Shipwreck Beach,” and now, all these years later, the wreck continues to give up its secrets one at a time.

In 1936 every preacher in the land had been praying for Monte Carlo’s demise. When the end came, every one of them took credit for it. What the law couldn’t do, God and Mother Nature did.

That day, and in subsequent years, ownership of the Monte Carlo remained unknown. Hence, everything of value not already absconded with by people on the beach, was collected by city officials. The hull was left to rot in our surf line, where it remains today. No one stepped forward to claim ownership, or to take responsibility for removing the old hulk.

This aerial of the shipwreck shows the bow already starting to separate. Tent City can be seen in the background. Tents by now (1937) had already been replaced with wooden rental homes, and Tent City’s popularity had begun to seriously decline. It would be gone in another two years. Photo courtesy Ernest Marquez.

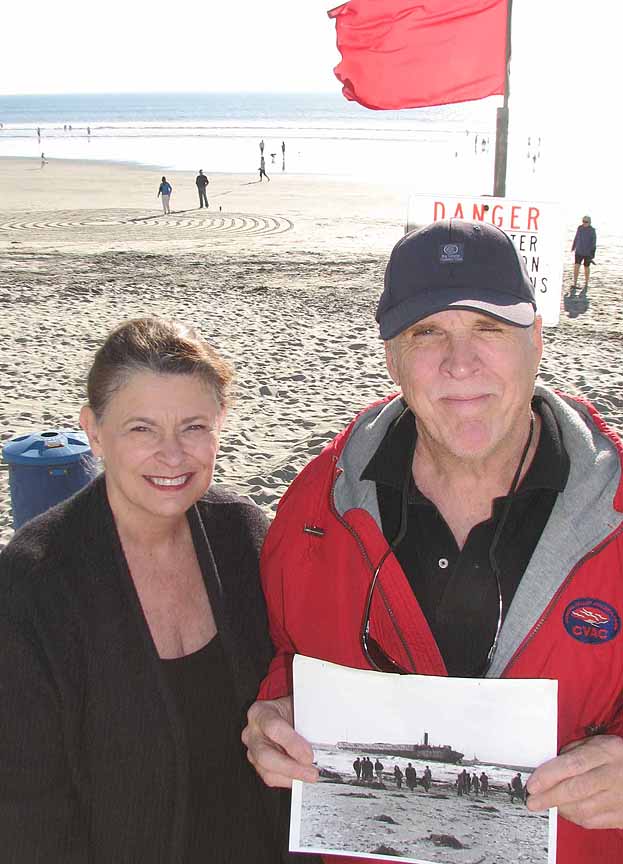

On New Year’s Day this year, on the 77th anniversary of that shipwreck, the owner’s grandson arrived on the beach to see the remains of Monte Carlo, a ship that was, apparently, a well-known “mystery” in his family too.

Stephen Turner and his wife Pam drove down from Newport Beach to see the wreck. Unfortunately, not enough winter storms had done their job, and the wreck remained obscured under tons of sand. Some years much of the ship’s outline can be seen it’s dark and foreboding holds filled with water, and rusty rebar protruding up from the broken spine of the hull.

Had Turner waited until this week, he would have seen his grandfather’s ship, or, at least, what’s left of it. The outline of Monte Carlo – the stern and amidships sections – are now visible at low tide. The bow broke apart in 1937 and has settled into the sand.

Pam and Steven Turner. He is the grandson of the Monte Carlo’s owner, at the site of the famous shipwreck, 77 years after the historic wreck. Photo by Joe Ditler.

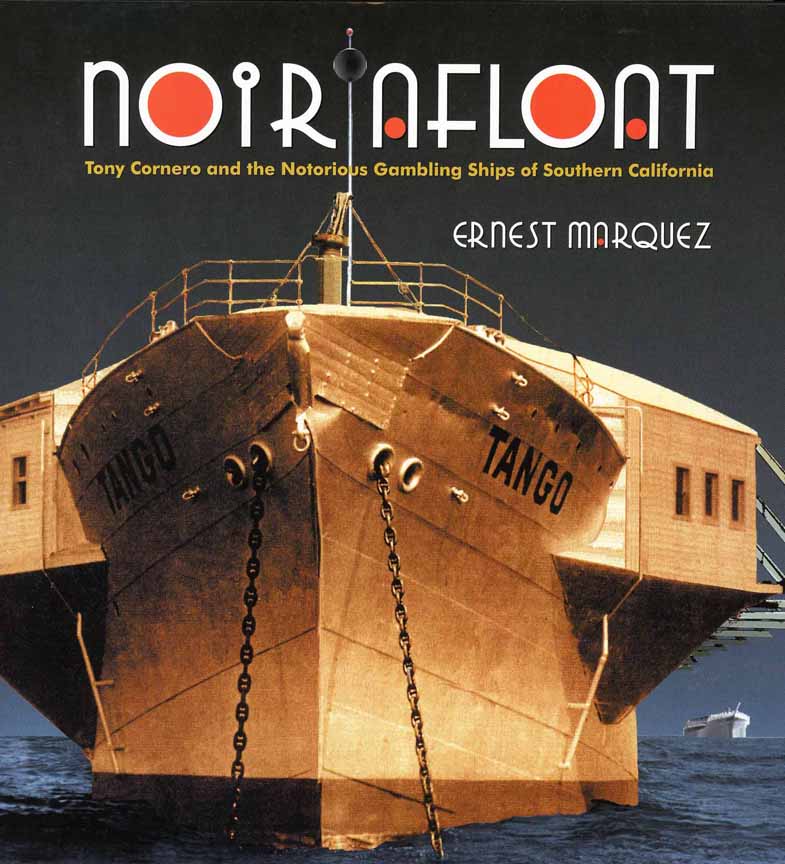

Turner has long had an interest in his family history, but what really kicked this into high gear was reading the 2011 book by Santa Monica historian, Ernest Marquez. The book is called, “Noir Afloat.” It chronicles the era of the gambling ships along the Pacific Coast and contains an entire chapter on Monte Carlo.

From 1927-1939 as many as ten gambling ships dotted the coast between San Diego and Long Beach ships named the Lux, the Rex, the Johanna Smith, the Rose Isle and the Monte Carlo.

They were reconfigured working ships, designed strictly for the purpose of gambling, prostitution and drinking. Past ship lives included former military vessels, five-masted barkentines, lumber schooners and even a former Alaska Packer ship, the four-masted Star of Scotland (San Diego’s tallship, the Star of India, was a former Alaska Packer ship).

This coffee table book, by Santa Monica historian Ernest Marquez, is a must have for anyone interested in the shipwreck Monte Carlo and that era of our history. There is an entire chapter dedicated to the Monte Carlo.

Everything written to date about the Monte Carlo and that infamous shipwreck of 1937 has come from local newspaper articles at the time of the wreck, and a handful of interviews with people who had either visited the casino in International waters, or were on the beach when she met her fate.

I’ve been fortunate to interview many; Katherine Carlin about what it was like on board the Monte Carlo; from Bud Bernhard sharing tales of swimming to the wreck and retrieving hundreds of silver dollars; Bruce Muirhead’s remembrances of having to truck gambling paraphernalia from the beach for the City of Coronado, but keeping enough wood to build his pigeon coops.

There was Dick Kenney’s tale of woe as he and his brother drove their Model A on to the beach in the excitement of that New Year’s morning only to have their car fall victim to soft sand and an incoming tide; and perhaps the best one, Ralph Mitchell’s attempt to claim the ship under the Rule of Admiralty Law (as it pertains to abandoned ships) after she hit the beach, only to be yelled off the ship by the caretakers.

Colonel Dick Kenney, who was on the scene the morning S.S. Monte Carlo became a permanent part of Coronado’s landscape, retrieved these silver Morgans from a dealer’s table he found in the surf line. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Now, thanks to the work of author Ernest Marquez, the bigger picture is seen. It’s a tale of opportunistic, small time gangsters eager to make a buck. While the entire operation is traced to gangster, bootlegger and gambler Tony Cornero, the presence of Al Capone in Coronado at that time raises speculation that he either had a stake in the gambling ships, or wanted to.

To lure customers offshore, Cornero offered free water taxi rides, a free drink, and even free dinner just to put guests in the mood to gamble. Orchestras played music while guests dined and gambled. Rooms were available as well. Few people came back without trying their luck. No one made money, except the owners of the ships and the syndicate that ruled them.

The Monte Carlo was built in 1921 at Wilmington, North Carolina, as a government-sponsored experiment in ship construction. She was built of concrete. She served two years in the U.S. Quartermaster Corps as Tanker No. 1. Then, in 1923 she was acquired by the Associated Oil Company of San Francisco and renamed the McKittrick. That work found her operating along the Pacific Coast for nearly a decade.

In 1932 she was sold, filled with cement to reduce motion on board, and converted into a gambling ship and named Monte Carlo. At 300 feet she was the largest gambling ship in the fleet. In her prime she hosted 2,000 visitors on weekends, and 15,000 a week. This is estimated to have paid off syndicate owners to the tune of nearly $3 million a year from the floating casinos. This, keep in mind, all took place at the end of Prohibition and smack dab in the middle of the Great Depression.

The spacious interior of Monte Carlo offered up dinning, drinking, gambling, prostitution and rooms to take your business private. In her prime, Monte Carlo hosted 15,000 people a week and the fleet of gambling ships brought in upwards of $3 million a year. Photo courtesy Ernest Marquez.

Her grand opening took place May 7, 1932, in anticipation of the 32 Los Angeles Olympic Games, and the hope they would attract tens of thousands of people to Gambling Ship Row. She was moored three miles offshore of Long Beach, with two other gambling ships of the fleet.

Billed as “the world’s greatest pleasure ship,” Monte Carlo was owned by Ed V. Turner and Marvin Schouweiler. It was Ed Turner’s grandson, Stephen Edward Turner, who found his way to Coronado January 1st in search of family history. He, it seems, learned more about his family from Marquez’ book than his family had ever known. And now we learn from both the book and from the Turner family some of the intricacies of this story that have eluded Coronadans for 77 years.

That fateful day in 1937, a small group of men stood off to the side as a feeding frenzy of pillaging took place by Coronado residents and guests of Tent City and the Hotel Del. They asked a young man, Bud Bernhard, to swim out and climb aboard. They offered him $20 if he would survey the damage on board and report back to them.

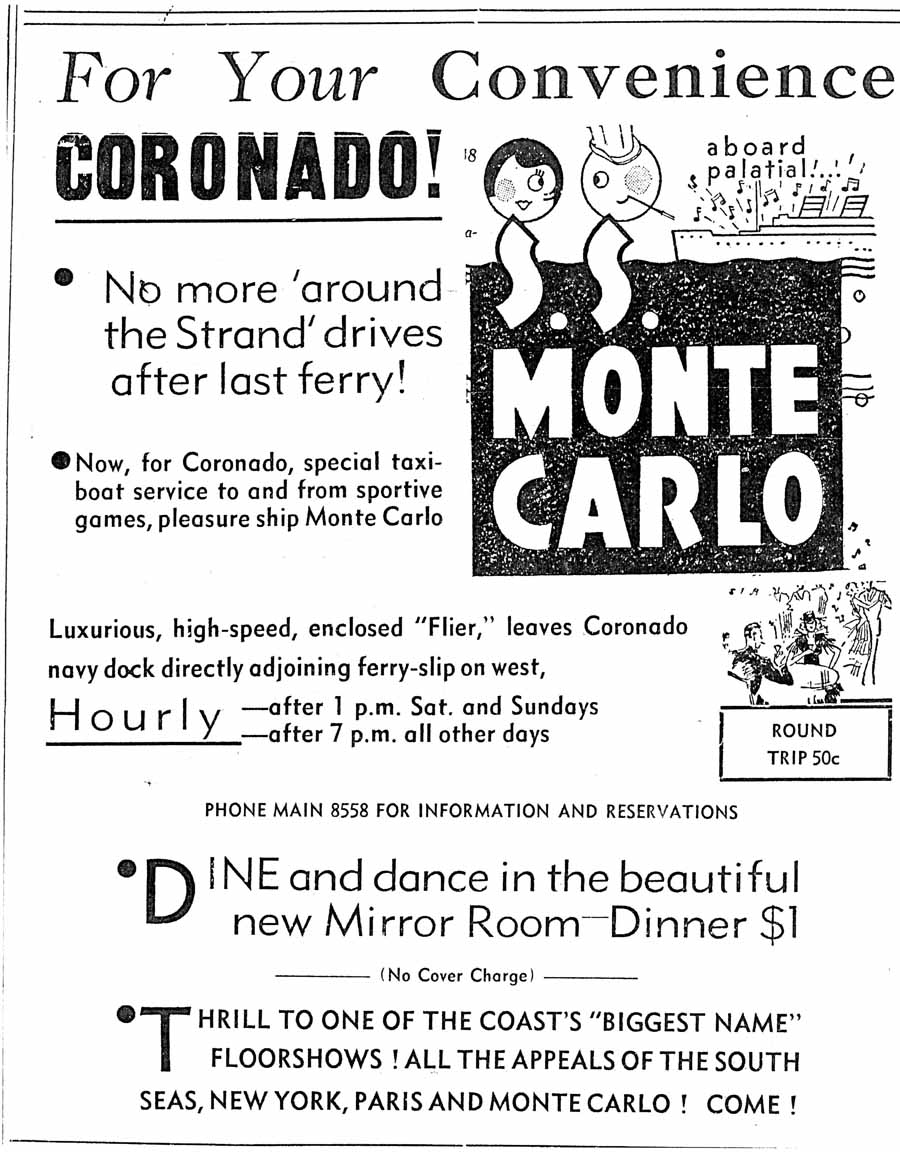

Even though Monte Carlo had a short career in San Diego, this ad was a familiar sight in the Coronado newspaper.

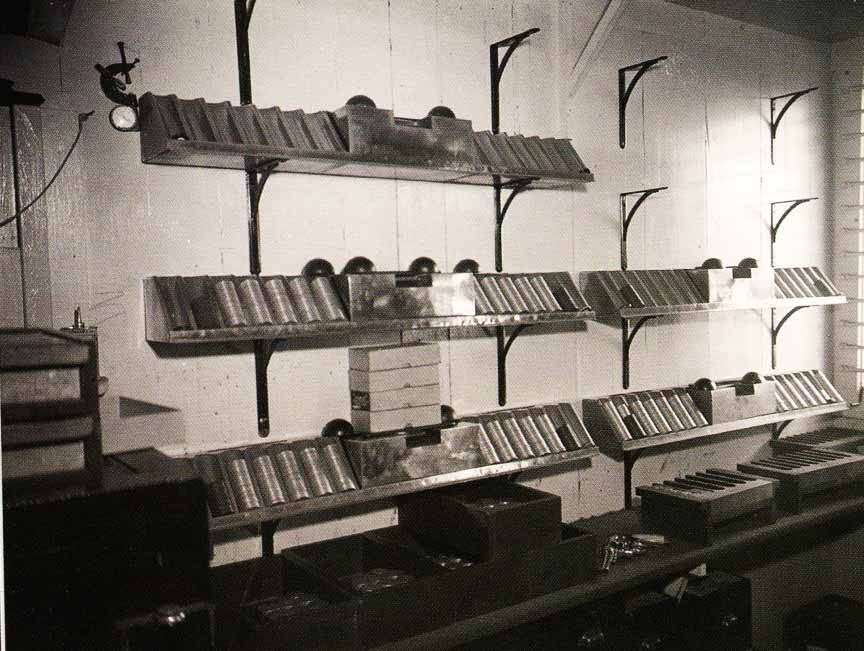

Bud saw destruction turned over gambling machines, booze bottles floating in seawater, and the sort of mess you would expect in the wake of a great flood, a hurricane or a shipwreck. But he also saw piles of silver dollars.

He grabbed a whisky bottle and made his way down the anchor chain and back to the beach where he reported to the men that it was a complete disaster, and nothing of value survived, except that whisky bottle. Bud would describe, years later, that the men represented the ship’s owners and that after his report they quickly left the beach, never to be heard from again.

Bud continued to raid the wrecked ship for weeks, filling his pockets with silver dollars. I have one of the silver dollars Bud retrieved, and it’s a proud possession.

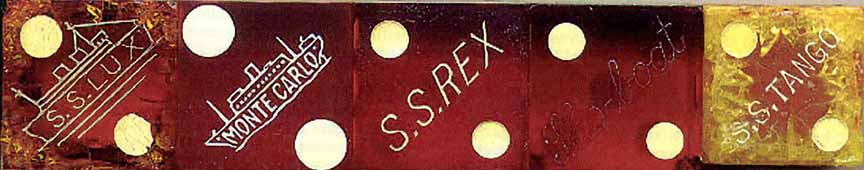

While few remain from the gambling ship days, we have a pretty good picture of what took place on board. Games of chance on Monte Carlo included craps tables, blackjack tables, roulette tables and wheels, chuck-a-luck and Chinese lottery, poker games and slot machines. Gambling on fights and horse (and dog) racing took place through new wireless devices on board. Dice were either weighted or edged to increase the house odds, and were etched with the name of the ship.

Above and below, Bruce Muirhead (white hat) can be seen collecting anything and everything of perceived value on orders of the City of Coronado. He would later tell how he hauled it to the Coronado Fire Station where it was locked up for “safe keeping.” Some of the wood Bruce used to make pigeon coops. He also recovered a bar stool that he donated to a local museum.

Photos courtesy Ernest Marquez.

Monte Carlo became part of San Diego’s landscape in 1936. She was towed here from Long Beach and anchored three miles offshore. For eight months she operated between Coronado and the Coronado Islands with slightly less success than she had seen in Long Beach, despite rumored visits from such Hollywood luminaries as Clark Gable and Mae West.

The San Diego District Attorney was helpless to stop what went on aboard Monte Carlo as she was moored in international waters. However, he could levy extreme taxes and permit requirements on the water taxis that carried people out to the ship, and he did. On November 1, after hosting a gala party on board, Monte Carlo closed for the winter.

On December 30 a storm began to punish the region. By the next night, 15-foot open-ocean swells battered the old ship and swept over her decks. The two caretakers on board John Miller and Art Gillespie tied down what they could and then found a place to brace themselves until the storm passed, firing flares into the air to attract help.

By daylight the ship was fast approaching Coronado beach. She hit hard. A Coast Guard cutter got close enough to launch a skiff, and the two caretakers precariously jumped from a Jacob’s ladder into the tiny skiff, timing their move so the rescue boat was on top of the swell.

Above, Jack Ditler (the author’s son), taken ten years ago. He’s exploring what must have appeared quite frightening to him at the time – the remains of the shipwreck Monte Carlo, suddenly visible after months of being covered by sand. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Above, rusted iron rebar periodically shoots up from the cement ship like a vicious Venus Flytrap looking for its meal. Many a swimmer and surfer has been wounded by the rebar. Each year, on the lowest tide of the year, the City of Coronado cuts it away with torches. They estimate they have cut tons of this metal from the shipwreck and it’s a never-ending process. Photo by Joe Ditler.

In 1974 Coronado saw the last of this enormous rudder post and steering gear. It was eventually cut away and hauled off by city workers. Today the most visible portion of the wreck is the lower deck, with square access portals and a lot of rust. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Before long the upper deck had washed onto the beach, which was soon littered with roulette wheels, gambling tables and bottles of booze. Perhaps the greatest treasure to be found on the beach that day was the lumber piles of first growth, long leaf Oregon fir used to build the new upper deck dining room with mirrored ceilings. Residents hauled it away as quickly as possible, and a few house additions in Coronado benefited from it a real prize during the Depression.

“We know my grandfather owned the ship,” said Turner, 65, a retired Real Estate developer, “but we don’t know whether he owned Monte Carlo at the time she was in San Diego.”

Turner’s father was president of Pacific Towboat and Salvage Co., based in Long Beach. That company, he said, was created from a fleet of water taxis the family inherited after Monte Carlo’s demise, as the gambling ship era drew to a close.

This photo shows racks of silver dollars inside the S.S. Monte Carlo before the shipwreck. How many racks like this, or how much silver remains, no one knows. Notice the handgun on the lower shelf. Photo courtesy Ernest Marquez.

“We know my grandfather was entrepreneurial. He had experience in the ranching business and owned slaughterhouses. We know he owned a bottle shop, but we don’t know if he was in the rum running business or to what extent his involvements were with the syndicate.”

One of the stories Turner shared was his grandfather’s tale of how the Monte Carlo’s gambling deck had wood-planked floors. Coins would frequently fall on the floor, and disappear through cracks in the planking. Searching in the ship’s bilge, employees would routinely explore for gold and silver coins, which they would pocket. Turner’s grandfather discovered the mischief and had the gambling floor covered with linoleum.

Turner’s family has an old roulette wheel and a pair of dice engraved with the ship’s name Monte Carlo. This is what perked their interest in researching more family history. They put the roulette wheel on eBay to see what, if any, reaction they would get.

Each ship had its own dice. They were weighted, and edges dulled, to increase the odds that the House would win, and not the gamblers. Photo courtesy Joe Ditler.

Before long a gentleman who had SCUBA dived all the shipwrecks and casinos along our coast contacted them. He had a bound book of newspaper articles about each of the ships. Another man owned the equipment that was used to make the dice for the floating casinos. And all of this led them to author and historian Ernest Marquez. The Turners decided to keep the roulette wheel, and now they are on a quest to find answers to many questions about their family history, which is what brought them to Coronado.

“I wanted to see what was left of the Monte Carlo,” said Turner. “My wife and I chose the lowest tide of the year, which coincidentally was the 77th anniversary of the wreck. Unfortunately, sand obscured the wreck. But we were thrilled to walk on that stretch of sand that now bears the name Shipwreck Beach,’ and with the help of old photos and local historians, we were able to imagine what that day must have been like. Now we’re moving forward to fill in the rest of the pieces of our family history.”

One comment from the l