Recent spills, beach closures, sick surfers and dead sea mammals have afflicted our local beaches in recent weeks. In fact, the entire Imperial Beach coastline was closed over the Veterans Day weekend. This raises the question of how beach-goers can monitor the water quality situation ahead of a trip to the beach.

As we reported earlier, the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) is the official body that works in cooperation with Mexico to sanitize sewage on the border. As we know, sometimes there are spills that pollute our waters. The IBWC states that it strives to know when those spills are and to alert others to avoid negative public health consequences. However, as we became aware early this month, the IBWC data gathering and reporting processes do not always work, so dead sea mammals and sick swimmers and surfers appeared to alert us.

So, if we can’t always rely upon IBWC to tell us when a spill has happened so that we know not to enter our beaches, who can we rely upon? How else do we learn about the water quality before we put on our bathing suits?

Currently, according to a June 6 statement by City Manager, Blair King, there are several entities that test the waters in and around Coronado including the cities of Coronado and San Diego, the County of San Diego Department of Environmental Health (DEH), the San Diego Unified Port District, and the Regional Water Quality Control Board. These agencies test different locations (sometimes the same locations, in fact) at different times and different frequencies. Few, if any, of these efforts seems to be very coordinated. But, the locations tested include North Beach on a weekly basis, Avenida Del Sol, Tidelands and Glorietta Bay as well as three locations along Silver Strand (by DEH). The tests are done generally each week (with some variation depending on season).

One primary issue for beach-goers is that getting the results of a water quality test takes time. Under most circumstances, it takes 48-96 hours to get results back. So, if a test is done on a Thursday at noon, say, the results will usually come back between Saturday or Sunday at noon. In other words, any beach-goers on Saturday might likely have already been in the water and exposed to pollutants before they would know.

48-hour Test Result Return Scenario

However, if the pollutants are concentrated enough, preliminary results can come back in 18 hours. So, a swimmer’s accidental exposure period would be narrowed to a day, in a time of concentrated pollution. That is, of course, if the contaminants entered the water at exactly the same time as the test was done. Since that is unlikely, a beach-goer’s possibility of exposure is almost always going to be longer than one day. The point is, it’s not very useful to get the results of water quality tests two days later for those who have had contact with the water in the meantime.

In addition to regular testing, the City of Coronado and other entities test after rainfall or any other event that they deem to have possibly changed the water quality (for instance, after a strong smell or actual sewage is seen in the water by surfers). One issue here is that even if citizens report sewage and/or smells, the testing entities might choose not to test if they do not also find the same evidence of a spill.

One solution to the problem of delayed results is to test more frequently. This will lessen the gaps in our knowledge, but it wouldn’t solve the problem of a delay. So, it is not a great fix to the problem.

A better solution would be a quicker test – one that would allow for same day results. In fact, a quicker test, known as qPCR, has been developed and tested. And, in fact, according to local activist and owner of Ark Environmental Solutions, Lance Rodgers, one has been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), but it is unreliable in salt water. According to Rodgers, “[quicker tests] have been tried by the county and run alongside existing tests to see how reliable they are [that is, do they consistently provide accurate information]. None have, as yet, been deemed to be reliable enough by the EPA. And so, none have been EPA approved.”

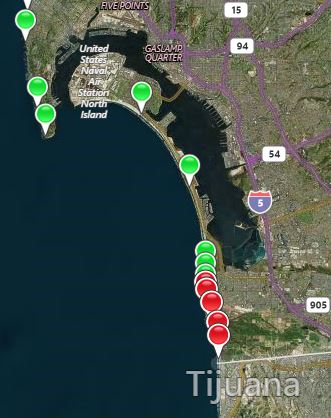

A second critical issue is that of disseminating the information. Where does a beach-goer get the information on the water quality tests? You can check ahead of time on the San Diego County beach water quality website www.sdbeachinfo.com. That website shows a map of the San Diego County beaches and marks each with a red (closed), green (open), or yellow (advisory) dot. If a beach-goer wants more detailed data on the date of tests and a breakdown of results, it is not provided there. But, it does appear to be the best way for beach-goers to check the status of beaches ahead of time.

A third issue is that the tests that are done on water quality test for a fairly narrow set of contaminants. The tests are Fecal Indicator Bacteria (FIB) tests that look specifically for enterococcus, total coliform and fecal coliform. These tests detect and estimate the level of fecal contamination in the water which can indicate a health risk. These are helpful, but they do not test for other threats that we often face in our waters, such as chemical agents, heavy metals, and other toxic chemicals.

Finally, while there are issues with the water testing which leave us with gaps in our knowledge about water quality, there is a total dearth of testing or, at least, reporting of the sand or sediment quality. Of course, when contaminated water comes into contact with sand or soil, it leaves contaminants. According to DEH, the sand would be clear of contaminants as quickly as the water is clear of them. But, we don’t have tests to demonstrate that.

So, more extensive tests, faster results, and better dissemination of information might all help the beach goer to know whether the water is safe to get into. But, they do not address the main issue – solving the problem to start with. The Coronado Times will take that issue up next.