The issue of cross-border pollution along the Tijuana River is one that has a variety of constituencies, with a variety of interests, and a multiplicity of approaches to solving what is undeniably a crisis. As earlier reported, the cities of Imperial Beach, Chula Vista, National City, as well as the Port and County of San Diego, have come at the seemingly never-ending crisis with an aggressive approach – they have threatened to sue the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC). In contrast, the City of Coronado, while supporting the suit with a monetary offer, has chosen to take the more diplomatic approach of lobbying.

Chris Harris, Secretary of Local 1613 of the National Border Patrol Council recognizes the disparity of interests with a welcoming approach: “It’s a big tent. There’s room for everyone. Everyone who cares about the environment one way or another. It’s a big tent. Join the party and let’s get this fixed once and for all.” And, he will do whatever it takes to make sure that everyone who will listen will know about the problem. He has spoken with countless media outlets, environmental activists, and politicians. And, he doesn’t just talk; he takes these people on a tour of the border region so that they can see directly the pollution that is visible in and around the Tijuana River.

Photos and video by Lucia Martin

Harris’ interest in the environmental disaster on the border comes from his own desire to keep the border agents safe. Harris, like others we have interviewed, says, “It’s been happening forever. But, it’s been getting worse over the last year.” It is only during this time that Harris, along with support from his local office, began tracking the number of border agents who were affected by the pollution.

Harris says that from about April to September of 2017, he saw 83 documented cases of rashes, chemical, and illnesses from contact with the pollutants: “I had a huge rash and had to go to the hospital and take two types of prescriptions, topical and oral … we finally pushed our guys, with help from local management … telling the guys ‘look, if you’re contaminated, if you have chemical burns, or rashes, or you’ve been ill, report it.”

It was not easy to get the agents to report ill effects. For many, being put in harm’s way and possibly getting injured is just part of the job. In fact, we met one of the agents, as Harris was taking us along the river, who had just been in a scuffle with someone crossing illegally. That agent had cuts and abrasions on his knees and arm. Harris insisted that the agent report the injury. The agent sort of laughed off the idea. But Harris told him to take care of it. After all, who knew how much worse it could get given that the agent was working in an area polluted by raw sewage, plastics, industrial waste and potentially other toxins?

Another constraint to reporting injuries and illnesses can come from bureaucracy itself. Harris says, “We were getting a downturn in reporting because guys were getting turned down by the Department of Labor, so they said, ‘Why bother reporting it?’ And, again we’re pushing them to document it. Absolutely,” he says, pointing to the clearly polluted river, “you went into that, you come out of it and you have a rash on your feet or chemical burns, report it.”

The number of agents affected is a large share of those actually working in the field within the San Diego sector. Harris estimates that about one-third of those who are actively involved in his station, in the field, have been harmed: “It’s not right … We’re willing to accept the normal risks that are inherent in law enforcement … that’s part of the job. Being shot at, I’ve been shot at three times, being assaulted, being robbed – I got hit in the head with a rock [and endured four years of serious medical issues]. We try to mitigate that. We wear vests, we try to do our best to not be assaulted. We don’t like it, but we accept it. But, what we’re no longer willing to accept … is working in a toxic waste dump. It’s not part of the job. That’s nobody’s job unless you’re paid to work in a toxic waste dump … and you’re wearing biohazard gear.”

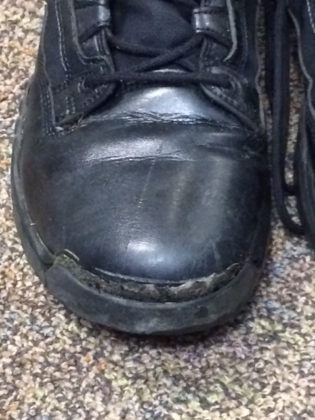

Harris tells about agents whose boots began to melt from the toxic pollution, and about agents who get skin reactions and chemical burns from going into the effluent of the Tijuana River and various canyons along the river. He turns to the history of the Vietnam veterans who were dying of cancer to illustrate his greatest fear. “My fear is, there are so few guys impacted that statistically I couldn’t say that this is from this. But, how do I know that my guy retires and at 63 he dies, how do I know that’s not from an accumulation of different things that he’s ingested over the years and the toxic metals. DDT is not banned down there. We know there’s DDT in the water … DDT, solvents, heavy metals. And we ingest these in different ways.”

Harris takes us on a tour of the border to show us some of the places where there is flow, but there should be none. He shows us areas where border agents are obligated to walk into the effluent and muck where they have to check bars over drainage tunnels to make sure they haven’t been compromised. At one spot, he tells of a time when “One of our guys saw footprints down there and had to go down to see if the bars were cut … When he finished his shift and showered, his boots had already started to dissolve. E-coli will make you sick, but it won’t dissolve your boots.” And, he shows us a spot which would seem to be a case study in the harm to the environment of using plastics.

Harris tells us that the daily flow is new since January. “I have a contention that the IBWC and the EPA have not tested for chemicals because they don’t want to know. That stuff is going into a collector which is going to a sewage treatment plant. That is not a chemical reclamation plant. That plant is permitted by the EPA [to treat sewage]. The discharge goes three miles out in to the ocean. The sediment, treated sludge, goes back to Mexico through those gates. My hypothetical is that if the U.S. government knew for a fact that there were those chemicals in here, my theory is they would have to pull the permit on that plant. They don’t want to know.”

But, Harris wants everyone to know. Harris hopes that getting the word out and getting policy-makers involved will lead to a solution to the problem. He says that Trump has tweeted about the issue and he believes “he’s directed things to be done.” At the same time, he knows he needs to keep people focused on this issue. The best answer, Harris believes, is to link Mexican commitment to the problem to the NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) negotiations that are currently taking place.

In a meeting that took place last fall in Washington, D.C., between the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, U.S. legislators and Mexican officials, Congressman Darryl Issa was quoted as saying that Mexico needed to take responsibility for upholding the environmental provisions of NAFTA: “We must not just have an agreement, but a plan of action.”

However, a recent public statement by the U.S. Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, at the conclusion of the Sixth Round of NAFTA renegotiations did not mention cross-border pollution issues. And Lighthizer’s overall assessment did not seem all that positive for those looking for a quick solution: “This round was a step forward, but we are progressing very slowly.”

On the other side of the aisle, Senator Dianne Feinstein recently made a specific request for $20 million to be put into the 2019 budget for the U.S. Mexico Border Water Infrastructure Program, at the urging of the Border Patrol Union. This might come more quickly and could perhaps mitigate the issues the Border Patrol is facing. Twenty million dollars will not be enough to resolve the crisis. But, it might be a place to start.