One summer Saturday on Coronado Beach, a group of teens walk past a small, yellow sign: “Keep out,” it reads. “Sewage contaminated water.”

They laugh, skim boards in hand.

“Oh no,” I hear one of them joke. “I’m so scared.”

The beach is peppered with people in the water – not as many as you might expect on a hot day at summer’s end, but plenty. The teens, if they grew up here, would have seen these signs their whole lives, rendering them meaningless.

My two-year-old shows me a shell he found.

“Oh no,” he echoes the older kids. “There’s poop in the water!”

“Yep,” I tell him, “But they’re trying to clean it up.”

Still.

How did it get this bad?

Sewage has been spilling into the coastal waters of San Diego for decades, with bureaucratic entanglement and limited funding stagnating relief.

As years passed, and with limited budgets for maintenance, more infrastructure crumbled, and the problem got progressively worse. Last year, the Tijuana River Valley faced an exceptionally wet winter, more crumbling infrastructure, and then a tropical storm, making matters worse. This year, Imperial Beach surpassed a staggering 600 consecutive days closed.

In 2020, a large federal funding package was allocated, and then stalled as the presidency switched hands, until it was ultimately awarded for the 2023 fiscal year. In January, it seemed that most of the repairs needed were funded.

But then, in an unforeseen blow, officials discovered that the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant needs $150 million in deferred maintenance costs, draining much of the available mitigation funding. The treatment plant’s expansion was initially estimated at $300 million, but in May 2023, after a feasibility study, it sits at approximately $600 million without anaerobic digesters.

As mitigation efforts trudged forward, an unprecedented fervor of grassroots efforts and political rallying erupted earlier this year, pressuring the Biden administration to allocate more funding – and more money is coming, the president says.

Meanwhile, 35 million gallons of sewage spill into coastal waters daily, and beach closures remain ubiquitous.

What’s the status of mitigation efforts?

About 40 percent of wastewater treatment assets are in need of repair, Maria-Elena Giner, commissioner for the US International Boundary and Water Commission, said at the October meeting of the California Coastal Commission.

But, she anticipates “incremental improvements” to the situation as initial repairs are completed by the end of November.

With limited funding, the IBWC decided that the most important project was rehabilitating and expanding the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant, which receives and processes excess wastewater flow. It was built in 1997, expanded in 2011, and it has exceeded its permitted flow most months since July 2022.

Between 2010 and 2020, only about $4 million was budgeted for the plant’s maintenance. It is in need of between $100 and $150 million in “urgent rehabilitation,” Giner said, and Tropical Storm Hilary exacerbated problems at an already vulnerable plant.

“It’s not looking good and it’s only gotten worse,” Giner said at an Oct. 31 public information meeting hosted by the Environmental Protection Agency. Its bar screens are clogged with trash and sediment, only three of six influent pumps are operational due to excessive wear and tear, its grit chambers and primary sedimentation tanks are overloaded. That means there is no solid removal, and solids carryover into secondary treatment.

The IBWC is working to bring the plant into compliance within 9 to 12 months, Giner said. The agency will solicit bids for design in late 2023, with construction projected to begin in early 2024.

However, Giner said the plant will improve incrementally starting in November as it begins receiving and replacing damaged pumps. The plant needs to replace 20 pumps, and about half have been ordered.

“Why does it take so long? Because unfortunately, you can’t just go to Walmart and buy a pump,” Giner said. They need to be identified and then specially manufactured.

Once the plant is in compliance, it will be expanded, with construction projected for 2025. Currently, it can process 25 million gallons per day, and that capacity will increase to 50 MGD, with a peaking factor that can treat temporary flows of up to 75 MGD.

The goal, Giner said, is to reduce untreated wastewater flows to the Pacific Ocean by 90% during dry weather, for a projected cost of $600 million.

What’s Mexico’s role in solving the problem?

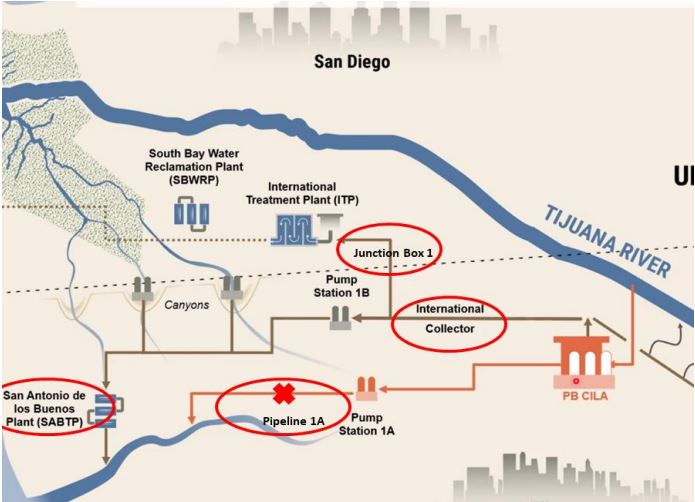

Another reason the SBIWTP is under stress is the rupture of a 42-inch pipeline in Matadero Canyon in July 2022, causing a loss of 25 MGD of wastewater treatment capacity. As a result, flows are diverted to both the Tijuana River as transboundary flows and to the SBIWTP.

Mexico is currently repairing the pipeline, with completion projected by the end of November. However, that pipeline carries untreated wastewater to the San Antonio de los Buenos Wastewater Treatment Plant, which is currently inoperable. So, that wastewater will still spill into the ocean.

“It’s not ideal that we’re sending raw sewage to the coast of San Antonio de los Buenos,” said Doug Liden, an environmental engineer for the EPA’s border liaison office, “But the alternative is that it’s going into the Tijuana River. The only thing worse than having wastewater enter the coast six miles south of the beach is it entering here.”

The idea, Liden said, is that the sewage will have more time to dissipate before hitting San Diego waters – and eventually, Mexico’s treatment plant should become operable again. The project repairing the SAB is going out to bid this fall.

Under Minute 328, a US-Mexico agreement signed in 2022 that outlines a joint effort to solve the sewage crisis, Mexico pledged $144 million over five years in rehabilitation efforts.

In the first year since the treaty amendment was signed, Mexico has secured approximately $45 million of funding. In addition to replacing the wastewater line to SAB and rehabilitating the plant itself, Mexico has started construction on the International Collector, another weak point in sewage infrastructure.

Other projects include Pump Station 1, whose construction will go to bid in early 2024, and the repair of a ruptured pipeline PB1A at Smugglers Gulch, which will be completed by the end of the month. Mexico’s pumping plant projects included PB CILA, which is completed, and Laureles I, whose construction contract is currently under procurement.

“Mexico is delivering on its commitment,” Liden said.

What’s the timeline for repairs?

It’s complicated. Although both the US and Mexico have given timelines for some projects, as outlined above, the US has not secured the requisite funding to solve all of its infrastructure problems.

The government is taking a phased approach to projects so that immediate repairs can begin as additional funding is solicited.

“Hopefully by the end of next year, there’s going to be a lot of construction going on in parallel with design, ordering of equipment, and phasing it out,” Giner said. “We want to ensure we’re having an impact on our beaches and our water quality sooner rather than later.”

However, even the $600 million estimate for repairs to and expansion of the SBIWTP does not include anaerobic digesters. Officials say they are working on a backup plan for procuring them, potentially via the North America Development Bank and private parties.

With limited funding, officials say, it’s about maximizing impact, but complete mitigation remains years – and millions of dollars of funding – away.

Will winter storms exacerbate the problem?

Historically, wet weather has increased beach closures. This is not only because storms strain treatment infrastructure, but also, because rain pushes trash and sewage from storm drains into the canyons and, eventually, through the Tijuana River Valley and into coastal waters.

At last month’s Coastal Commission meeting, a longtime surfer described during public comment surfing in Imperial Beach and hitting trash – including, once, a dead dog.

Because of this, even when repairs are made to wastewater treatment plants, trash will remain a problem. At a meeting of the IBWC’s Citizen’s Forum, trash booms were proposed to prevent solid debris from entering the ocean.

Over the last three decades, Tijuana’s population has skyrocketed, causing rapid urbanization that strains the city’s sewage infrastructure, the California Water Board reports. In addition, an estimated 40% of new construction in Tijuana is built without permits. Often, unpermitted dwellings will drain sewage into storm drains.

Ensuring homes in Tijuana are connected to sewage lines is a priority, Liden said.

“We are holding ourselves accountable,” Giner said. “We agree that it’s unacceptable that you do not have access to your beaches, it is unacceptable that you cannot use the public amenities of the estuary, and it’s unacceptable, the health impacts associated with that.”