Written By , Voice of San Diego, August 2, 2022

Republished per content sharing policy

Federal officials crossed the border Tuesday morning to assess the damage from the latest sewage disaster on the Baja side.

The good news is that Tijuana isn’t currently pumping sewage to a broken wastewater treatment plant called Punta Bandera that effectively spills it, untreated, straight into the Pacific Ocean.

The bad news is, that’s because at least one of a critical set of pipes that gets it there is completely busted in half. The other is precariously perched atop a crumbling cliff face.

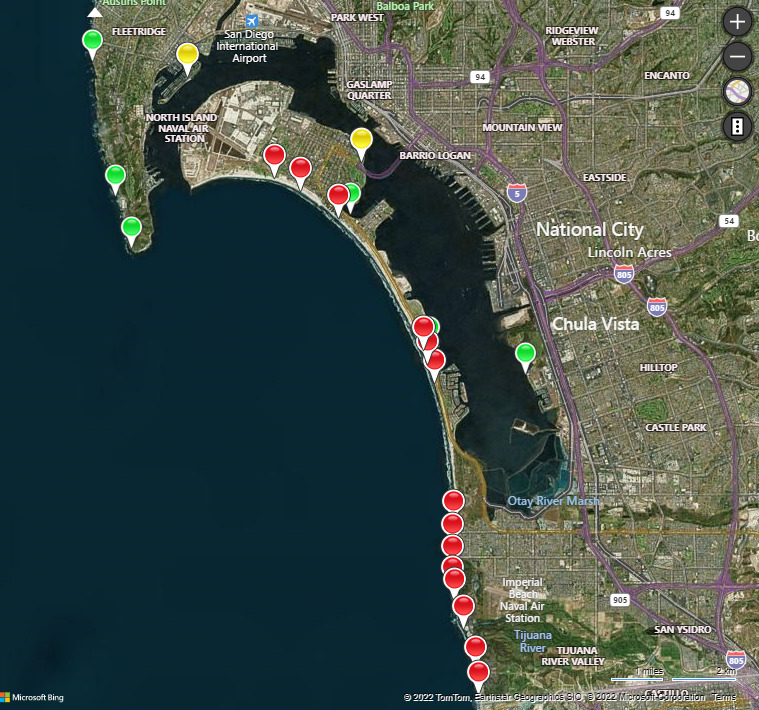

That means a lot of the sewage that would otherwise be flushed into the sea about six miles south of the border is making its way into the Tijuana River. The river’s mouth empties into the ocean just below the city of Imperial Beach, and the coast is currently experiencing particularly strong swells from a hurricane in Baja — all conditions ripe for ushering that sewage up the coast and spurring beach closures in Southern California.

Officials from Baja’s State Public Services Commission, or CESPT, said this all began Saturday when the agency was repairing one of those pipes. Something went wrong after those repairs, causing too much pressure in the pipe, which then blew an air venting device at the point where the pipe drops into Matadero Canyon.

Geysers of sewage spilled from that blown device, which began eroding the cliff face, exposing a neighboring pipe that eventually snapped in half. CESPT had to shut off pumps that send sewage west through those pipes in order to fix it and ensure they didn’t lose both to the canyon.

As of Tuesday morning, Matadero Canyon was mostly dry because the pumps piping sewage there were turned off and no longer leaking. But the spill left behind huge clefts along the canyon walls. A severed pipe hung awkwardly from the cliff face and the other looked brazenly exposed, jutting out from the dirt atop a small, poured concrete base.

On the other side of the border, there was standing sewage water outside Smugglers Gulch, the U.S. side of Matadero Canyon. It’s hard to see the Tijuana River itself, but it’s glistening outline could be spotted from the ocean and through the river estuary near a U.S. military aircraft landing base.

Because Tijuana isn’t sending sewage to its own plant due to this break, that means the International Wastewater Treatment plant will have to, at times, take on twice the flow it was built to treat. And, that more contaminated river water continued its path toward the sea.

“This is exactly why we want to expand the International Wastewater Treatment plant,” said Doug Liden, an environmental engineer with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “The whole point of our projects is to get rid of these (pipe)lines because it just doesn’t ever make sense to pump this wastewater uphill, all the way to the coast, especially when it’s not getting treated anyway.”

The EPA is spearheading a $300 million suite of projects to reduce cross-border sewage spills from Tijuana into San Diego. First on the docket is expanding the international treatment plant to treat sewage that would otherwise go to Punta Bandera, and hopefully retire these frequently failing pipelines for good.

The latest spill provided a unique look at how the International Boundary and Water Commission, or IBWC, works. It’s a little-known federal agency that straddles both nations but handles water and sanitation issues, legal agreements, negotiations and interprets treaties. Mexico’s counterpart is called Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, in Spanish, or CILA. Each side has its own commissioner, lead engineers and foreign affairs officers.

When Morgan Rogers, the current operations manager of the IBWC’s treatment plant on the U.S. side, heard about the latest spill, he arranged to meet his Mexican counterparts at the scene atop Matadero Canyon. CILA officials took Rogers, Liden and a representative from the California State Water Resources Board, Keith Yaeger, into the canyon to view the damage.

Trucks were already busy scooping fallen canyon debris and filling in erosion around the pipelines. A backhoe dug out huge pieces of sewage pipe buried in the canyon’s floor as workers looked for a place to reconnect the broken pipeline.

Mexican officials on scene estimated it would take at least a week to fix one pipe and get sewage partially flowing again. They asked Rogers to borrow a pump and a vacuum from IBWC to complete some of that work and exchanged ideas for how best to approach the remaining repairs.

Together, these two pipes can pump about 75 million gallons of sewage per day towards the broken plant on the Mexican side. On Tuesday those pipes should have been carrying about 20 million gallons per day, federal officials estimate. But without them functioning, IBWC estimated about half of that would make its untreated way into the Tijuana River and eventually the ocean, and the U.S.-side plant is picking up and treating the rest.

For context, a San Diegan consumes about 140 gallons of water per day. So, if that effectively became sewage, the Tijuana River is taking on as much sewage as about 71,000 San Diegans create. This spill is also larger than the region experienced during a mysterious spill in January, later attributed to a different problem with a pipe on the Tijuana side.

Despite the impending sewage flow, Imperial Beach was fairly busy Tuesday afternoon with beachgoers boogie boarding and surfing in the water. New blue signs from the County of San Diego warned residents the water may contain sewage and cause illness. But Nicole Perry brought her kids to the beach and everyone swam anyway. It’s a cheap activity for her children to get out some energy while school is out, she said.

“You have to pick what risks you take,” Perry said. “We’ve been living through COVID and social distancing. Where the heck are we going to go to get a little bit of breathing room?”

She said locals know not to go in when they can see the water is brown and dirty-looking. It’s usually so in the wintertime and much smellier, Perry said, pointing out that the shore waters looked clear with hues of blue and green.

Despite failed water quality tests, a known and official report of a sewage spill from Tijuana and southern swells from a hurricane further south in Baja, the beaches weren’t officially closed.

Gig Conaugton, a spokesperson for the county, said the county and lifeguard staff have not observed the spill reaching the ocean- meaning discolored water or odors.

“When the spill reaches the ocean, that is when beach action to close the beach water contact is taken,” Conaughton wrote, adding the county is closely monitoring the flow of sewage in the Tijuana River valley.

VOSD Update: Soon after this post published, the county announced Imperial Beach was closed to water contact.

Written By MacKenzie Elmer

Written By MacKenzie Elmer

MacKenzie is a reporter for Voice of San Diego. She writes about the environment and natural resources.