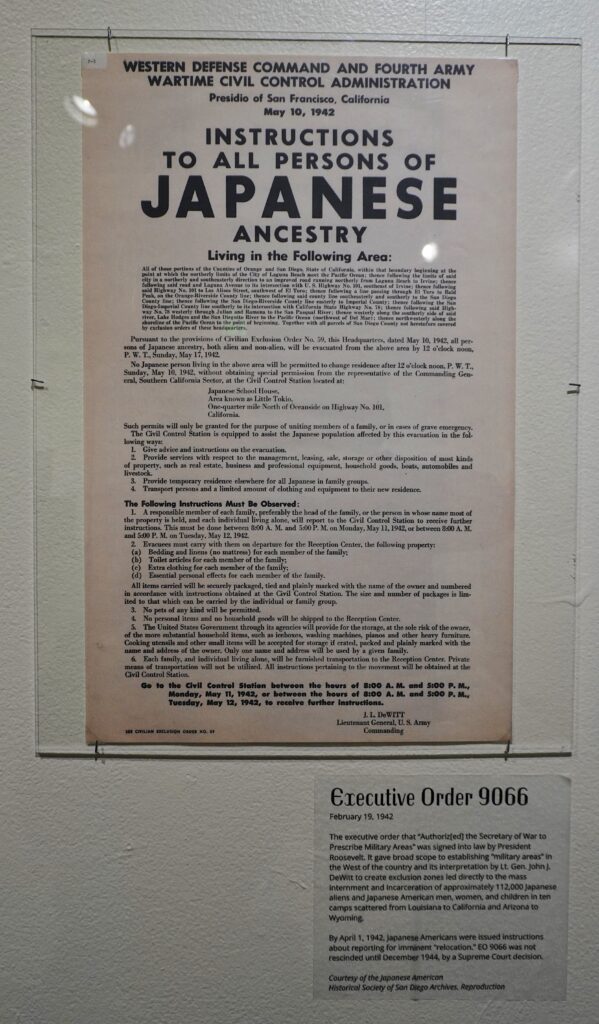

February 19 marked the 80th anniversary of Executive order 9066 which allowed for the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. In honor of the many Japanese-Americans who suffered locally and across the country, the Coronado Historical Association is currently hosting its ‘Uprooted: The Story of Japanese Americans in Coronado’ exhibit.

Vickie Stone, the Curator of Collections at the museum, has compiled a variety of photos, videos, interviews, documents and other artifacts that help to tell the story of some Japanese-Americans during the war.

The first room of the exhibit at the historical association is in great contrast to the rest of the story told in the museum. Entering the first room, one is greeted by eye-catching kimonos and koinobori, or koi kites. Other traditional items like tea sets and lanterns are kept behind glass cases for a look into traditional Japanese culture.

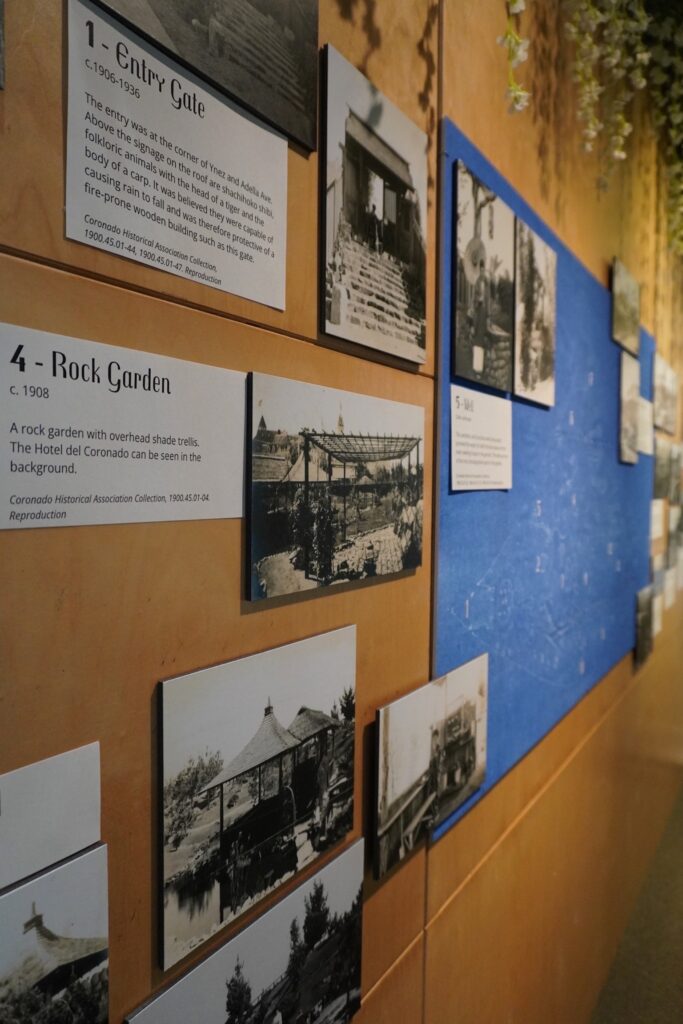

The highlight of the room is a blueprint floor plan for the original Coronado Tea garden, a popular tourist attraction which opened in 1901 and closed in 1936. Each numbered room on the floor plan corresponds to a small description, put together with the help of a local Japanese gardener Kaz Abe, who helped with identifying the features on the map.

Another person that helped with the exhibit is Japanese American Setsuo Iwashita. Iwashita was instrumental in providing first hand accounts of his family’s personal story of incarceration during WWII and then growing up in Coronado and later graduating from Coronado High School.

After leaving the first room of the exhibit, a curious museum-goer will find themselves face to face with some of the United States’ less impressive history. When the war began, anti-Asian laws were put into place in California, including caps on immigration, exclusion from citizenship and laws against interracial marriage. The exhibit features photos of both the laws enforced at the time and the people whom the laws were enforced against.

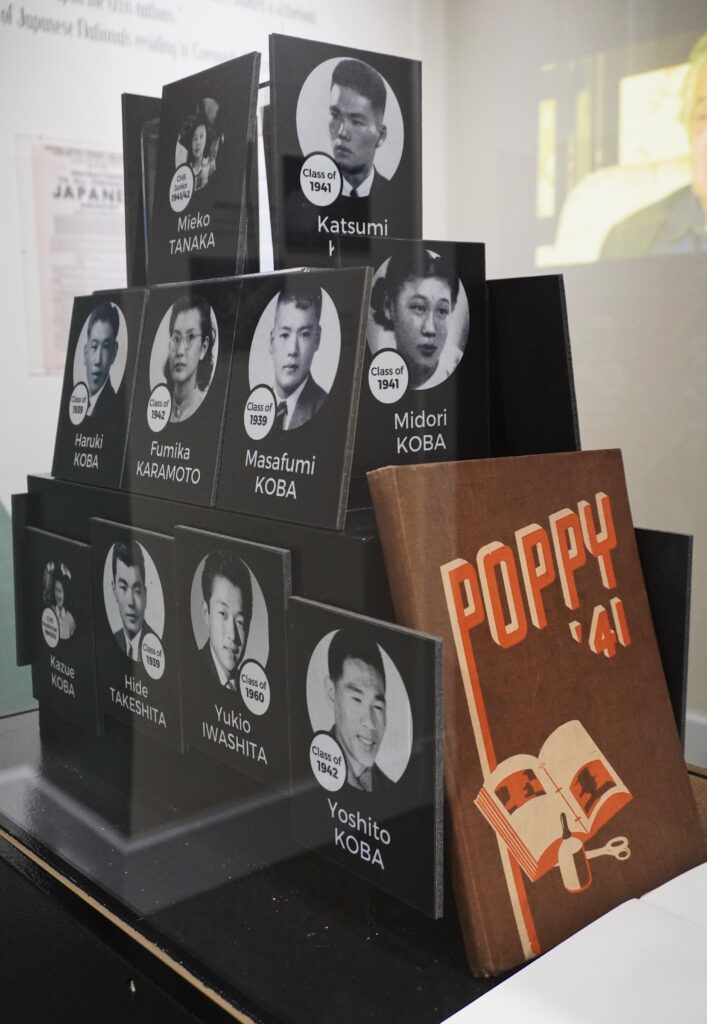

One of the most interesting and shocking parts of the exhibit is a collection of yearbook photos from a Coronado High School yearbook. Many graduates in the year leading up to and during the war were Japanese immigrants. These students, who were a part of the Coronado community, were soon scrutinized and treated as lesser-than because of where they came from.

“I think a lot of people are really surprised that people in their own community were taken away from their homes,” Stone said.

Despite the actions taken against Japanese-Americans, many still chose to serve their country. Around 14 individuals from Coronado enlisted in the segregated unit 442 of the United States Army. Unit 442 went on to be one of the most decorated Army units during the war.

“I think people really didn’t know that their own community members were serving their country in that way,” Stone said. “It’s a hidden history that we’re bringing to light.”

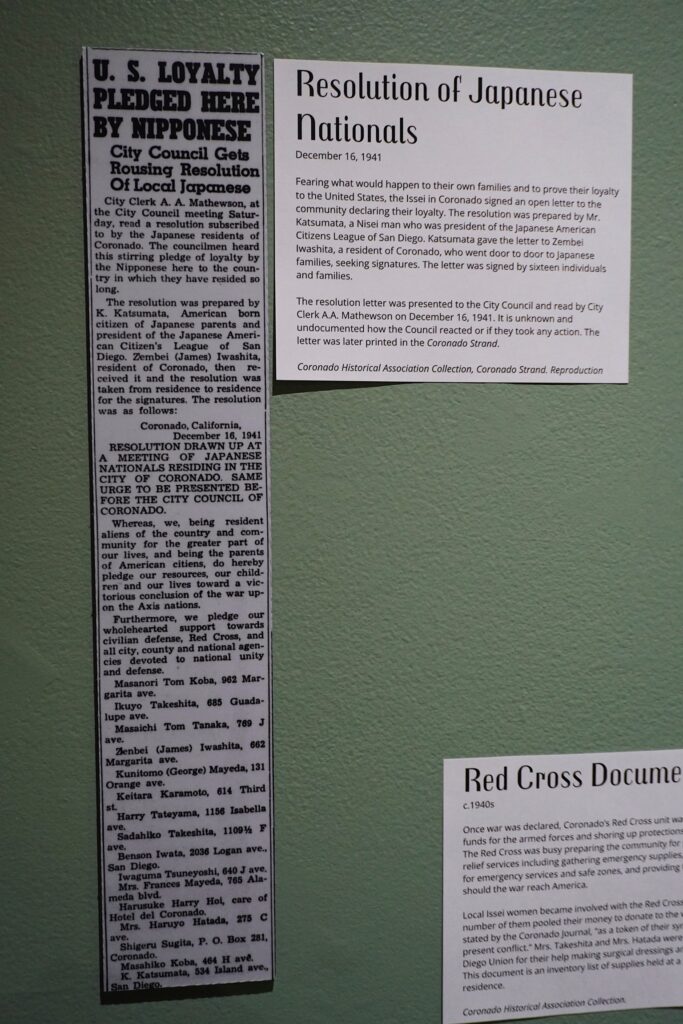

Other local Japanese-Americans promised to dedicate their lives to the US in a letter addressed to the Coronado City Council.

“We…do hereby pledge our resources, our children, and our lives toward a victorious conclusion of the war upon the axis nations,” reads a quote on a wall of the exhibit, taken from the Resolution of Japanese Nationals Residing in Coronado.

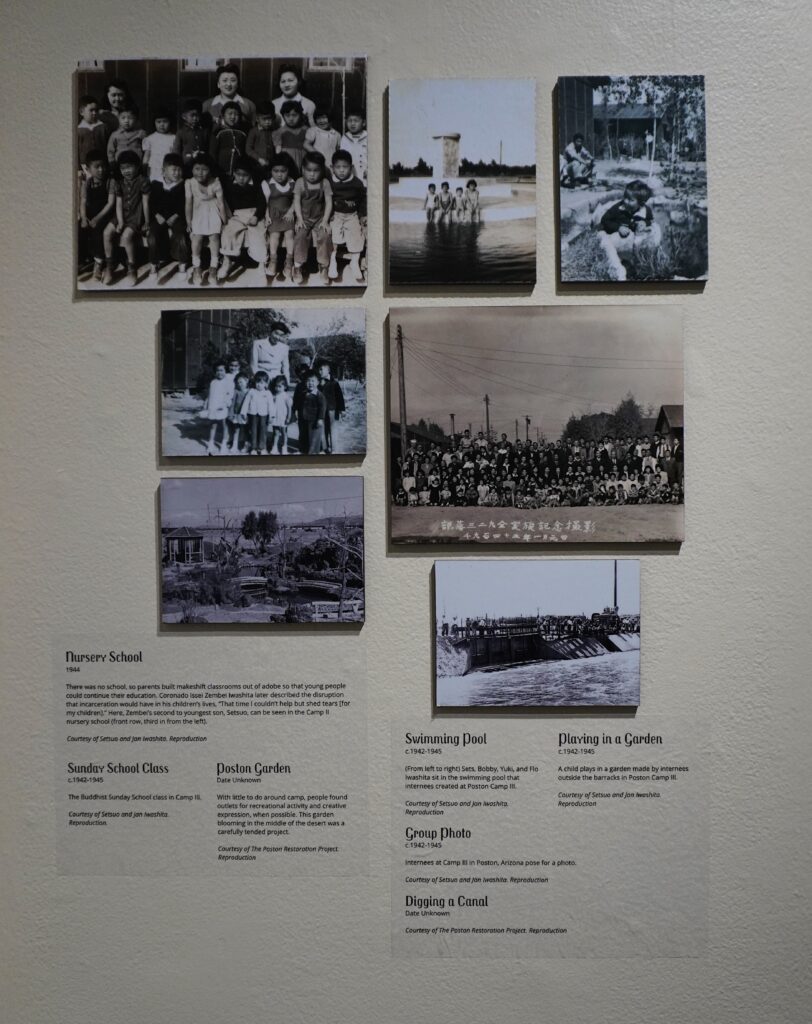

There are multiple walls in the exhibit dedicated to showcasing life in the internment camps, specifically Poston, Arizona where many Coronado locals were sent. Living conditions were subpar and Japanese-Americans were forced to live in small, un-insulated huts in the middle of the Arizona desert.

After the war, Stone said that two families returned to Coronado, although they did not return to the life they once knew, as their property had been given away and they now owned very little.

The final room of the exhibit focuses on Unit 442 and its many achievements, as well as the Redress movement which called out the government for its wrongdoings and demanded justice for Japanese-Americans. Unfortunately, many of the reparations did not make their way through government approval until many of the survivors of the internment camps had already passed away.

Visitors to the museum can also take advantage of QR codes in the final room, which link to the emotional testimonies of some such survivors.

“It’s our job as historians to tell full stories in all their messiness,” Stone said. “History is really multifaceted and it’s a lot more nuanced than just good guys and bad guys. I think it’s important that we take a look at those nuances and we take a look at the dark sides of history to really make sure we’re not repeating those kinds of things going forward. I really hope that people come and learn a lot in this exhibit and I hope they celebrate the people who lived, and still live, here in Coronado, and just celebrate history.”

Coronado Historical Association Uprooted Exhibit