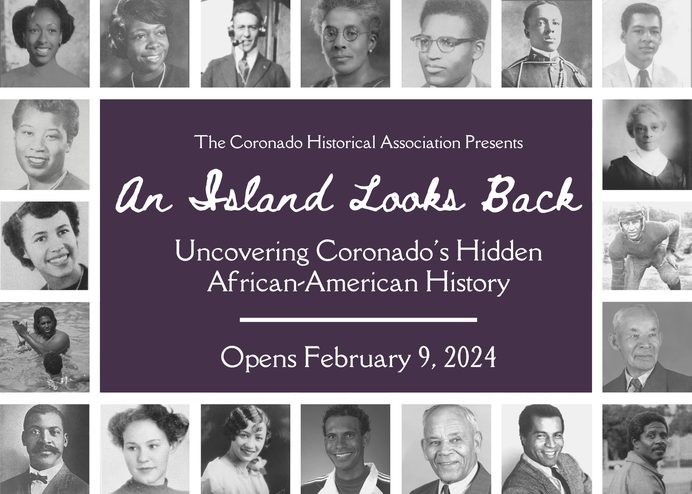

It’s not easy telling stories that have been erased from history. Just ask Kevin Ashley, a local historian who’s curating his first exhibit, “An Island Looks Back: Uncovering Coronado’s Hidden African-American History” opening at the Coronado Historical Association on February 9.

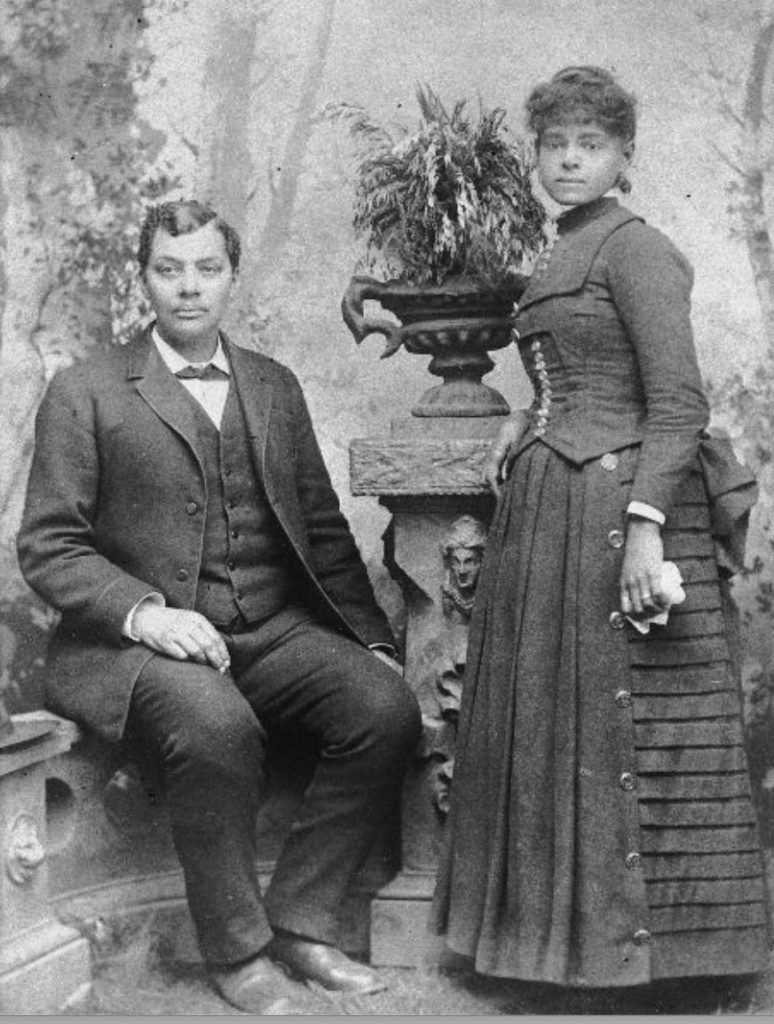

“Between the 1880s and the 1920s, Coronado had a thriving Black community, with a population that was [proportionally] triple the size of the African American population in the state of California,” said Ashley. “They were homeowners, civic leaders, ran local businesses, went to local schools and were stars on the football field in the 1910s. Many were military veterans, including three Civil War veterans and four Buffalo Soldiers.”

But no one knows about them.

Their pictures don’t line the walls of city buildings. Their achievements are unknown. But the exhibit at the Coronado Historical Association is changing all that. Finally, Coronado residents can learn about the triumphs and challenges that faced local Black Americans from the late 1800s all the way to present day, according to Ashley.

“The pictures in the exhibits will speak for themselves,” said Ashley. “People will find plenty of examples of difficult and traumatic history and equally incredible stories and inspiration and hope.”

Among historical documents, visitors will find everything from early pictures of Coronado’s integrated schools to photographs of early life in Coronado. The exhibit features photos and documentation of Black families growing up in the Federal Housing Project on the bay in the 1950s, and recent photos of Coronado High School grads and athletes by local photographer Kel Casey.

Piecing Together the Exhibit

Ashley says the exhibit is a cumulation of eight months of work in the “rabbit hole,” unearthing old photos and documents from newspapers and other museums. But when he was first asked to curate an exhibit on Coronado’s Black history by Christine Stokes and Vickie Stone from the Coronado Historical Association, he hesitated. They wanted to apply for a city grant for the project, but only if Ashley signed on.

Ashley wasn’t sure if the timing was right, or if the public was ready for such an exhibit. But Stokes and Stone said, “trust us, they’re ready.”

Ashley agreed to do the exhibit on one condition: that the exhibit was an “unflinching look back.” They agreed.

“They said, ‘that’s what we do as historians, we have to tell the whole story,’” recalls Ashley. “It isn’t about assigning blame; it’s about sharing history.”

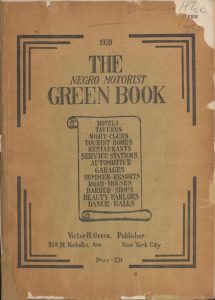

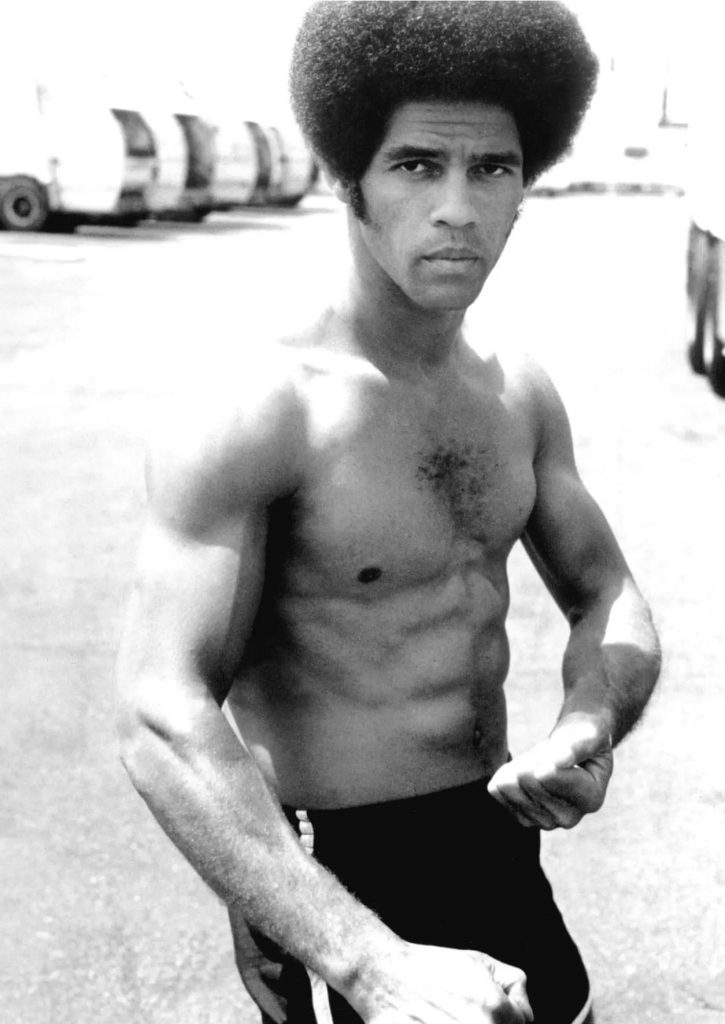

In his research, Ashley dug up some surprising new information. He found out, for example, that a Coronado home was listed in the “Green Book,” which was a travel guide listing businesses that didn’t discriminate against Black travelers. He also found photos and information about actor Jim Kelly, who was perhaps the first Black action film star and ran a tennis training club in Coronado. Ashley also discovered that the beach where the Coronado Cays is today was once called “Anderson Beach,” named after a successful Black businessman, and was the site of many Black community gatherings and celebrations.

He learned about the Black families that grew up on bay in the Federal Housing Project in the 1950s and 1960s, and how fondly they remember Coronado.

“They tell me it was a great place to be a kid, and they say they didn’t experience overt racism while living here,” said Ashley. “They say the kids in Coronado embraced them.”

He learned that three of the last 13 homecoming queens of Coronado High School were Black, yet only 1% of the student population is. In 1956, he learned that the “most popular” award went to a Black student.

“That has to tell you something,” he said.

But he also found many unsavory examples of racism in the past, as well as references to challenges that Black residents experience today.

“Black Americans today still have incidents which have happened in Coronado, so it’s not like we are living in this color-blind society that people talk about and wish for.”

He said it was important to the exhibit’s advisory committee—which is made up of Black residents and former residents, descendants of Coronado’s first Black families, including CHS graduates spanning from the 1950s to today—that the full history be shared.

“Their stories will be told,” said Ashley. “As hard as it is, people need to know.”

What Happened to Coronado’s Thriving Black Community?

Finally, Ashley learned more than a lot about “redlining” and discriminatory real estate practices which prevented Black Americans from renting and owning property in Coronado. He said the use of racially restrictive covenants and deeds was both “widespread” and “striking.”

This practice helps explain why, in the 1920s, things started to change for Coronado’s Black community. Ashley was surprised to learn that while the Black population of San Diego grew to 5-6% of the population from the 1920s to the 1960s, in Coronado, it shrank down to almost nothing.

These changes were facilitated, in part, by the National Association of Real Estate Brokers which released a Code of Ethics in 1924. Article 34 of the Code of Ethics says that a realtor must never “introduce into a neighborhood a character or property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to the property values of the neighborhood.”

“So now you have Coronado realtors and real estate associations basically making sure that African Americans who lived in the old neighborhoods felt, on some level, unwelcome, while at the same time, not letting any new ones in,” said Ashley. “Basically, realtors became the agents of segregation in the United States for at least 40 years.”

Even with the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968, Ashley says it took another 20 years after that for the first African American family to succeed in buying a house in Coronado.

“I was only able to confirm one house in Coronado being sold to an African American in 60 years,” said Ashley. “That’s going to be one of the more uncomfortable things that’s shared in the exhibit, he said.

In 2020, the National Association of Realtors issued a formal apology for their discriminatory practices.

Working from a History, Erased

Ashley says that while there were many stories about the Black experience in Coronado, finding photographs and information for the exhibit was a challenge, as very little of Black American culture was preserved.

“If you want to understand how bad the situation is, you go down to the original Black community in the Gaslamp, and it’s gone,” said Ashley. “There’s almost nothing. And if you walk over to Imperial Avenue, which was the Black Wall Street in San Diego, same thing…it’s gone.”

But Ashley was able to find photographs and news articles by researching online, including published stories from the California Eagle which is a Black newspaper out of Los Angeles. They also borrowed items from the San Diego History Center and other museums.

It begs the question: why was Coronado’s Black past erased? Ashley says it’s a common theme across the country.

“Black history has been erased everywhere,” he said. “Whether consciously erased, or subconsciously, that’s for other people to decide. But it’s not unique to Coronado.”

He says for one reason or another, the subject of the Black history is like “kryptonite” for a large portion of America.

“It’s so hard for some people to accept that for decades, African Americans were denied equality in this country,” said Ashley. “No one wants to tell hard stories and hard history. Some people feel guilty, other people feel angry, and it’s just easier not to go there.”

The Mark of a Healthy Community

Ashley says he’s a little nervous about the exhibit opening, as he’s come to know these historical figures like friends and wants to do their stories justice.

“It’s a bit nerve-wracking because I’ve lived with these people in my head for the last three years and I’ve really come to love and respect and cherish them,” he said.

But with the blessing of his advisory team and his family, as well as the hard work of the CHA staff, Ashley hopes the exhibit will be a healthy exercise in awareness and truth-telling.

“Every community in America, in every city in America, owes it to the residents past and present to honor as full as possible the history they can tell,” said Ashley. “It’s clearly a healthy community that’s willing to come out and tell the full story of what the experience is of its residents.”

The exhibit opens Friday, Feb. 9, 2024 and runs through May. The Coronado Historical Association is located at 1100 Orange Avenue.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on Feb. 8 to remove some historical examples of racism that might be triggering, but will be found in the exhibit.

RELATED: