If there’s one thing every Coronado resident has in common, it’s a strong sense of community.

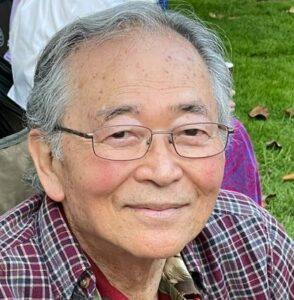

This shared sense of community, that seems to touch every corner of the island, is why many Coronadans will likely be shocked to hear Setsuo Iwashita’s story.

Sets Iwashita was born at the old Coronado Hospital on Orange Avenue in 1940, and by April of 1942, when he was just 14 months old, he was living in a prison camp made for Japanese-Americans at the height of World War II. He and his family were sent to prison without even a court hearing.

Sets Iwashita was born at the old Coronado Hospital on Orange Avenue in 1940, and by April of 1942, when he was just 14 months old, he was living in a prison camp made for Japanese-Americans at the height of World War II. He and his family were sent to prison without even a court hearing.

Sets and his family of six, his parents Zembei and Tamiko (who was pregnant), older sister Florence, older brother Bobby, and Sets were forced onto trains headed to a location not disclosed to them. The family was only able to take the things they could carry in their arms, and for the Iwashita family that meant formula, diapers and clothing for their children — including Sets’ younger brother who was born on their first stop at the Santa Anita Race Track, Los Angeles, in a horse stall where they lived for four months until the next leg of their journey.

Those sent to the camps were shocked when they were only given two weeks to dispose of all their possessions, many selling a house full of furniture and belongings for less than $100. Sets also said his family’s bank accounts were taken from them, leaving them with no money, as were other valuable items like cameras, radios, and guns that they were then required to turn in to the police station. He wonders what ever happened to their 1937 Plymouth.

The Iwashitas were taken from Santa Anita, along with 18,000 other prisoners from the West Coast, by train to Poston, AZ Internment Camp. They were housed in tar papered barracks that were 100 feet long by 20 feet wide, and split into fourths so four families could live in each section. The section each family lived in was only 25 feet by 20 feet with one light bulb. There was no insulation from the desert heat or the freezing winter temperatures late at night and nothing to keep the bugs out. The barracks had no running water, so no bathrooms or kitchens; each person had to walk to the latrines and mess hall buildings. There were no dividers on any of the bath or toilet stalls, and many women would go to the bathrooms in the middle of the night to use the facilities because of their embarrassment. Residents of the camps built their own school buildings out of adobe for their kids.

Much of Iwashita’s childhood experience is highlighted in the Coronado Historical Association’s exhibit, Uprooted.

Outside of the prison camps, Sets said, there was another kind of attack on Japanese-Americans.

William Randolph Hearst is a name familiar to most Americans, especially those living in California. Hearst’s Castle is touted as a tourist destination, with lavish architecture sprawled across acres of land.

But there’s a side of Hearst that isn’t shared on the guided tours. Hearst published many ugly and untruthful anti-Japanese stories in his papers which only fueled the racist fire burning in the heart of America. The papers called them spies and animals, and these sentiments were widely distributed across the west and beyond.

When the Iwashitas and other Japanese-Americans were in camp, some of them chose to return to Japan because these law-abiding citizens had been treated so poorly by the country they lived in for years. Of the 15 or 16 Japanese-American families who once lived in Coronado, only three returned.

The trouble for those who did decide to return to Japan, Sets said, is that there was little left of the island country. The U.S. had bombed the entire nation, and two cities were hit by atomic bombs leaving the country useless.

“There was nothing left in Japan, they didn’t have much of a choice,” Sets said of the decision many faced on whether or not to return to Japan.

And whether or not Japanese-Americans chose to stay or leave, it wasn’t as if they had any money or property left to their name.

One of the most surprising things Iwashita shared was his mother Tamiko’s story. She was born in the United States, February 1914, while her father attended Stanford University. Her family moved back to Japan when she was five years old along with two younger sisters. She grew up waited on by three servants in Japan and when she was 18 her parents had arranged her marriage to Zembei Iwashita who was from the same prefecture (county) as Tamiko. Zembei had been living in Chula Vista since he was 16 years old with an uncle and aunt on their farm. Zembei returned to Japan to marry in 1933, both came back to San Diego and farmed before moving to Coronado.

At the end of the war when the internees were released, the Iwashita family still found ways to aid other Japanese-Americans in similar positions. They helped families find housing, even as they themselves were living in shacks and garages on friend’s farms with no indoor plumbing nor kitchen. Sets said his father always put others first.

The Iwashitas were finally able to move back to Coronado sometime in 1946 by the generous offer of work from E.F. Hutton, a well-known stock broker. Mr. Hutton’s Isabella Avenue estate (previously owned by the great Enrico Caruso, one of the top tenors of the world) boasted a three car carriage house with a one bedroom apartment above it where the Iwashita family of six could live. Zembei became Hutton’s gardener as the only jobs given to Japanese-Americans were as gardeners or farmers, regardless of their education.

But the discrimination didn’t stop at jobs and housing. Sets attended school in Coronado but could only read Japanese in the early years of grade school. In high school he was many times accused of cheating on tests even though he was sitting in front of the teacher’s desk. It was not until years later that he realized why he had been accused; it was a result of the teacher’s discrimination.

This kind of treatment continued, even when he would travel with his wife Jan. He recalled a story of a time the two of them went to a meal together at a diner. He said, because he was a Japanese man, that they were completely ignored by any servers in the restaurant and eventually chose to leave.

Despite many instances of blatant discrimination, Sets has always been loyal to the United States. He was commissioned a Lieutenant into the US Army, and even after being imprisoned as a child by the only country he knew, he felt it was his duty as a good citizen to fight for America and all the freedoms it affords us and others.

Jan shared that it wasn’t until the last decade or so that Sets had begun to open up to her about his experience in the prison camps. It wasn’t something anyone in his family ever spoke openly about, because of the shame they felt surrounding their situation. Sets, however, is slowly changing that narrative. He said he has begun to share more with his two children and three grandchildren, as well as with the Coronado Historical Association to ensure that his story is not forgotten.

For those that have taken the time to listen to, or read, Iwashita’s story, he hopes they will walk away with, “We’re not the kind of people that the imprudent William Randolph Hearst made us out to be in his 28 major newspapers and 18 magazines he owned.”

Although political tensions are currently running high, he does not believe that anything like the prison camps will happen again. The amount of easily accessible news and the way information is disseminated today is so different compared to WWII and would prevent any repeat of history.

Sets is a proud U.S. citizen, one who believes it was only right for him, and others, to risk their lives for their country, despite how he was treated. He said he believes in acting in such a way that would not bring shame to his family or country.

Watch a recorded interview with Setsuo Iwashita, courtesy of the Coronado Historical Association:

If video doesn’t play, click here.

RELATED:

CHA’s “Uprooted” Exhibit — Taking a Look at a Dark Side of History So We Don’t Repeat It