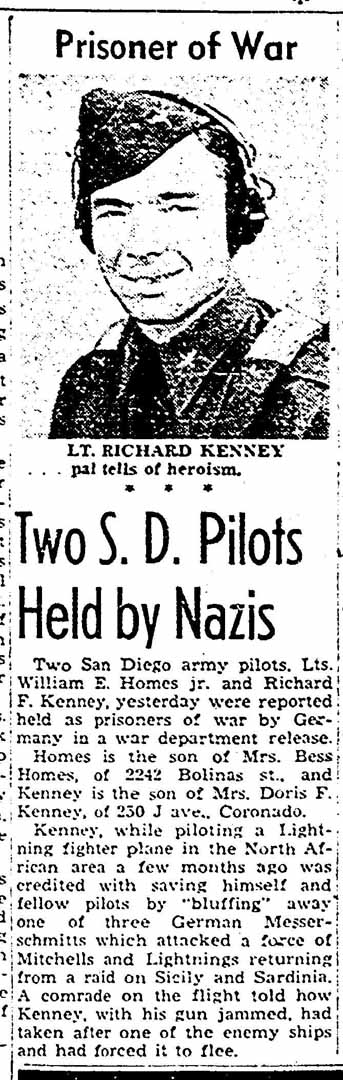

HE FLEW P-38S OVER NORTH AFRICA

AND SURVIVED STALAG LUFT III AS A POW

Cabbage stew, Red Cross parcels, severe punishment and drafty bunkhouses became an accepted way of life for Dick Kenney during World War II, but not before the young pilot took his toll on the enemy.

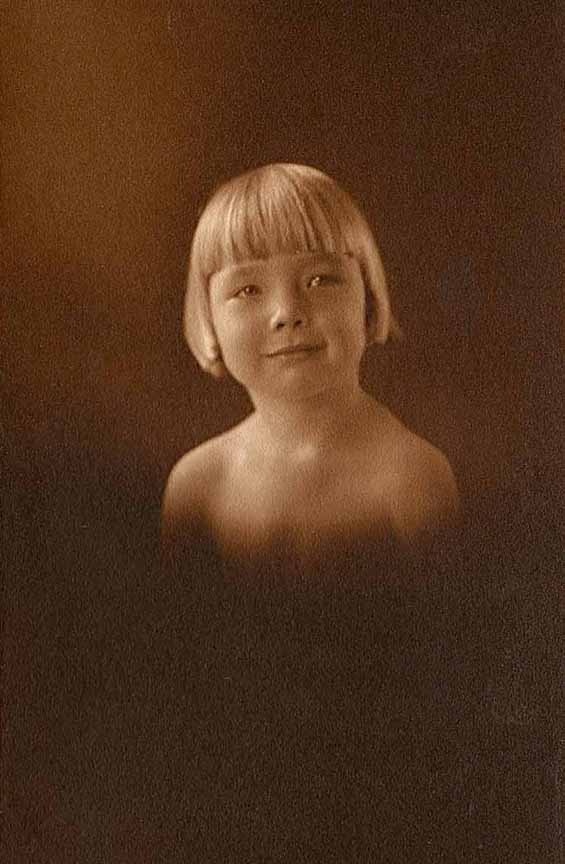

Richard F. Kenney was born March 2, 1920, in Santa Cruz, California as one of five children to Lt. Patrick John and Doris Kenney.

A typical baby portrait of the 1920s, Dick Kenney would later hide this photo under stacks of other things, just so his friends wouldn’t see it and tease him about it.

His father died when he was young and Kenney was raised by his mother in Coronado, California where he gained a reputation for being a big kid who liked to work and play with equal passion.

He excelled as a junior sailor throughout the late 1930s, winning numerous regattas at the Coronado Yacht Club in Star boats, Great Lakes scows, and the Sunbirds of the Rainbow Fleet. He graduated from Coronado High School, class of 1938. He was the last surviving member of that class.

Until two years ago, Dick Kenney and his high school friend Ralph Mitchell would have lunch together at the Brigantine and share old stories. Ralph died, and it is believed Dick Kenney was the last survivor from Coronado High School’s Class of ’38.

Kenney obtained his pilots license in 1940 at the Clyde Corley Flying School at Lindbergh Field. In September 1941, after a brief stint on four-stacker destroyers, he went into the Aviation Cadets at Cal Aero in Chino, California. He completed flying school in 1942 and was commissioned second lieutenant before being assigned to a P-38 squadron stationed at Hamilton Field just north of San Francisco.

Soon after that Dick Kenney deployed with the 82nd Fighter Group out of Los Angeles and then flew with the 95th Fighter Squadron in Ireland and North Africa.

As a kid growing up in Coronado, Dick Kenney got into his fair share of mischief. He would often tell stories of derailing the trolley with blasting caps purchased at the Coronado Drug Store; of pelting police officers with rotten tomatoes; and of exercising horses for the polo players at the Coronado Polo Grounds.

Kenney was on the troop ship Queen Mary in 1942 en route to Europe when he got this first taste of the war. During evasive maneuvers to avoid Nazi U-Boat attacks, the converted cruise liner hit one of its military escort cruisers, slicing it in half and killing more than 300 men.

“We watched helplessly as wreckage floated past our portholes,” he would recall years later. The reality of war had hit home rapidly for the young pilot eager to fight for his country.

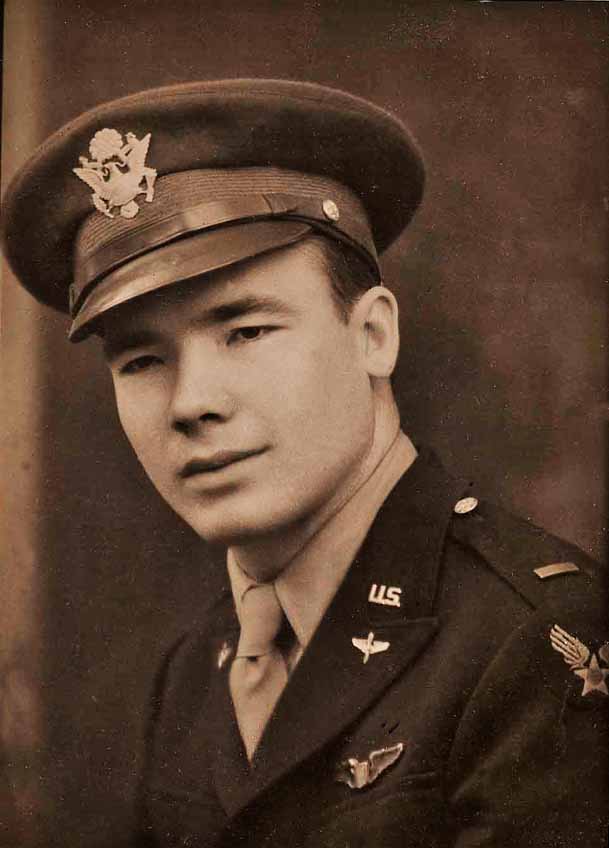

This shot of Dick Kenney was taken just before his final flight – a mission where he voluntarily placed himself in the last slot, knowing ground fire would probably take him out. It did, and he spent the remainder of the war in notorious Stalag Luft III. Years later he would say that he just couldn’t put the other, younger, more inexperienced P-38 pilots in that slot. He was of the opinion, like so many other young sailors, soldiers and pilots, that he was invulnerable in any situation.

Kenney’s airplane was the P-38 Lightning, one of the most significant aircraft of World War II and a veritable killing machine. On April 28, 1943 while flying his P-38, Kenney bombed an Axis merchant ship and shot down a Messerschmitt ME 109, resulting in his receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross.

An official description of his actions read like a Clark Gable movie script: “Undaunted by a solid wall of flak and machine gun fire thrown above the ship, [Kenney] attacked broadside, planted his bomb squarely amidships, and passed a few feet over the ship. The merchant vessel was left at a complete standstill belching black smoke and steam after the explosion.”

The P-38 Lightning. The Germans nicknamed it “The Forked Tailed Devil.” It had a number of roles in both the Pacific and Atlantic Theaters – dive bombing, skip bombing, ground attack, aerial combat, night fighting and photo reconnaissance. Drop tanks under the wings gave them incredible range, and they could go toe-to-toe with anything the Germans or Japanese could put in the air.

Kenney came in low and fast (200 mph) and made a direct hit on the largest ship. His plane was directly over the ship when his bomb exploded, and the resulting shock wave flipped his P-38 upside down. Disregarding his own safety, he kept his eyes on the ship long enough to watch his wingman’s bomb explode on the doomed ship’s deck.

Suddenly, the radio squawked. It was one of our bombers flying overhead, warning Kenney of a group of Messerschmitts dropping in on his plane in search of easy prey. Kenney righted his aircraft only to find himself in a head-on run with one of the Messerschmitts, guns blazing. Kenney won that duel as the Messerschmitt flamed and then crashed into the sea.

On another mission Kenney attacked a flight of six Italian transport aircraft (SM-82). He took out the rear transport, and then the next. As he took a bead on the third transport, a Messerschmitt assigned to cover the transports dropped out of the ceiling and opened fire on Kenney’s P-38.

Kenney wheeled his plane around and shot down his attacker. That, including the two SM-82s, gave him a total of four confirmed kills. It was a big day as pilots go.

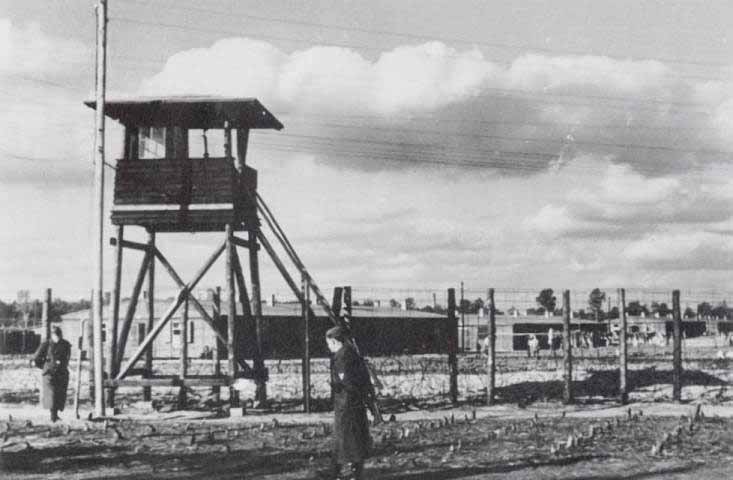

Stalag Luft III was home for allied pilots, and their guards were German Luftwaffe. Conditions were not pleasant, but the Germans treated their prisoners far better than the Japanese did their prisoners. At Stalag Luft III there was an undercurrent of esprit de corps as both prisoners and guards shared a love for flying.

Later, while escorting a flight of B-25 bombers over Sardinia, Kenney and his wingman were under attack by several Messerschmitts. Kenney’s wingman took down one of the German planes but the air was a mixed up portrait of planes and hot lead. Kenney’s guns jammed and his wingman had to switch gas tanks so they decided to hit the deck for home at about 400 miles an hour. The Messerschmitts had the altitude in their favor, however, and weren’t ready to give up the fight.

“They were dropping down on us fast, and their bullets were exloding at maximum range just outside my canopy,” recalled Kenney. “We couldn’t outrun them so I signaled my wingman to turn back into them. He shot at one and missed, shot at another and it went down. The second plane ran for it and I had the third one in my sights but my guns were jammed.”

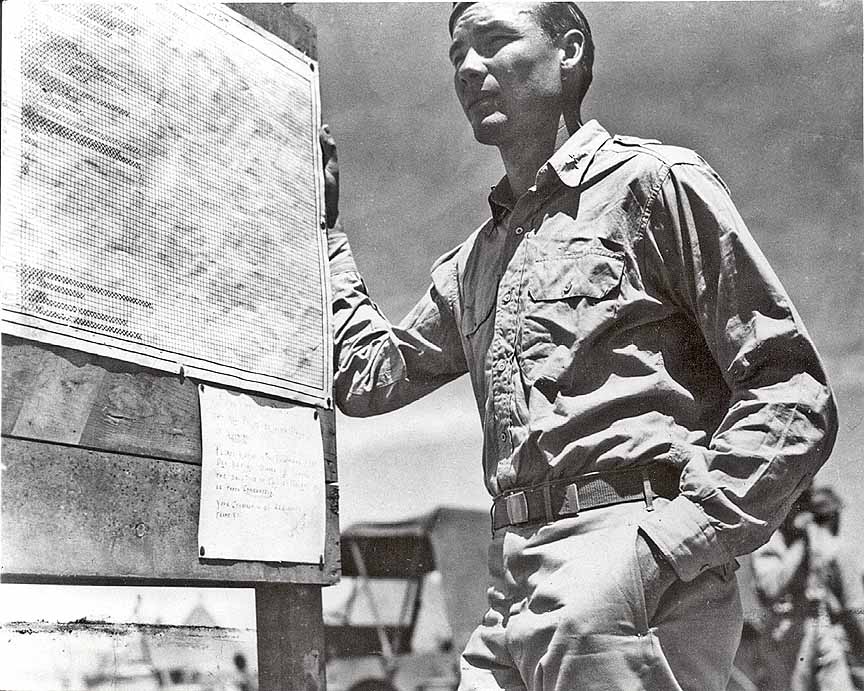

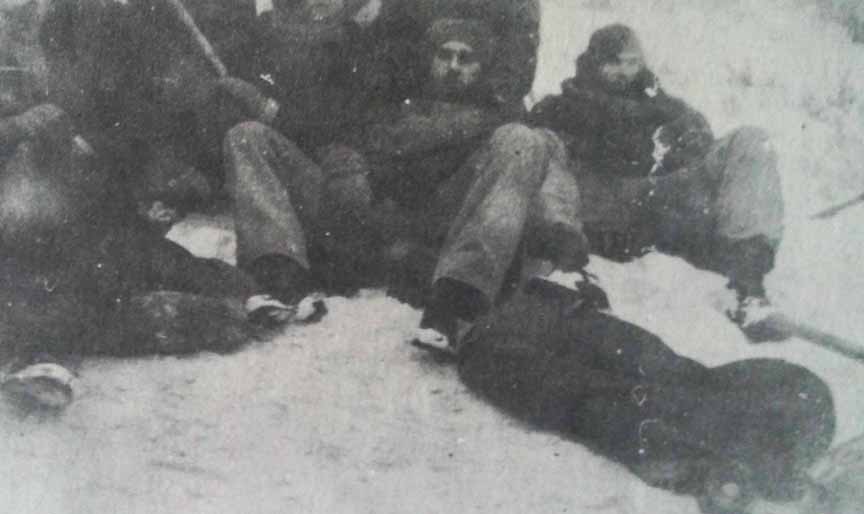

The German death march of 1945, in the worse storm in 50 years to hit Europe. Colonel Kenney would recall years later that prisoners and guards ahead of them would toss everything they had – food, guns, etc. – along the side of the road. If prisoners tried to pick them up, they were shot.

Kenney’s jammed guns preventing him from scoring a fifth kill that would have given him ace status, however, and despite having no firepower of his own, Kenney saved his wingman by boldly bluffing the third enemy plane out of the air.

That action resulted in a United Press International story that hit newspapers back home. The headline read, “Coronado Flier Bluffs Enemy.” Richard Kenney complained about that fifth elusive kill until his dying day. He received his first Purple Heart from wounds received in action while flying out of North Africa, in June of 1943.

This rare shot of prisoners resting during the death march of 1945 shows Dick Kenney, far right facing the camera. Many died during this march. Dick got frostbite so badly that he thought he would lose his toes and feet. 68 years later a man read his story in the San Diego newspaper and called Kenney up. “I think you qualify for a second Purple Heart for injuries sustained in that march,” he said. The Colonel would have nothing to do with it and snapped back, “I already have a Purple Heart.” Friends of Kenney, however, pursued the project and, 68 years after the march, he proudly held that second Purple Heart in his hands.

Two months after bluffing the German pilot out of the sky, Kenney was sent on another mission to fly in low and strafe a radar tower in Sicily in preparation for a B-25 bombing run. As acting operations officer he intentionally put himself in the final slot, knowing that his pilots were young and inexperienced, and whoever flew that tail position would take a lot of heat from the ground guns.

“There was never any other option,” he recalled years later. “I knew the ground fire would be dialed in by the time our final plane made its pass. There was no way I was going to put someone else in that position.”

Dick Kenney’s dog tags from Stalag Luft III.

That decision took Dick Kenney out of the war for the duration. His left engine was hit by surface-to-air ack-ack fire, engulfing the plane and pilot in fire. Unable to reach the water, Kenney crashed on a Sicilian farm with severe burns over much of his body.

He was captured and taken to Palermo where he received some treatment for his wounds. Kenney was interrogated, had a gun put to his temple, and was thrown into solitary confinement before being incarcerated in a POW camp as the “guest” of Adolf Hitler.

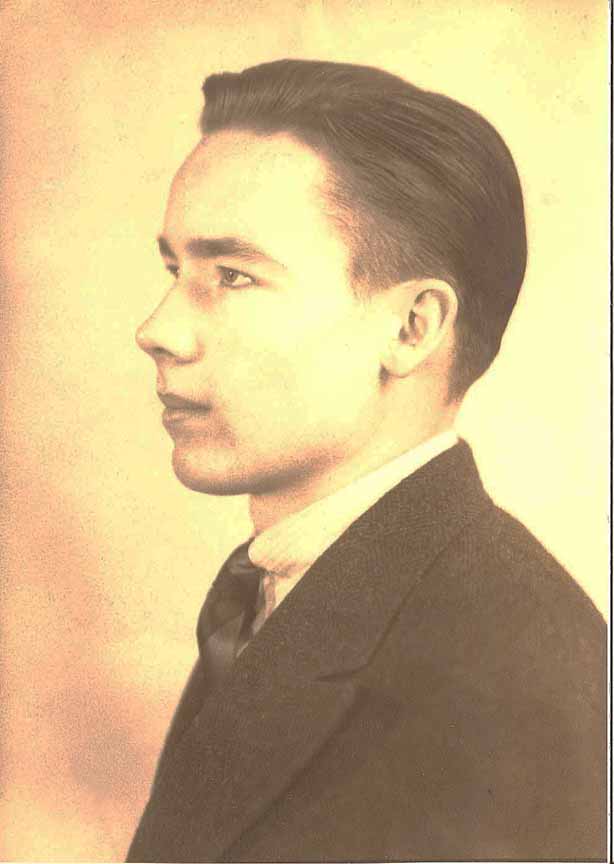

This portrait of Dick Kenney was taken in 1949.

One of the camps he was to call home for two years was Stalag Luft III, 90 miles southeast of Berlin in what is now Poland. Stalag Luft III was inspiration for the movie “The Great Escape,” throwing a light on Kenney’s misfortune that gave it (and him) celebrity status in the years to come. While he was not one of the prisoners trying to escape, he worked night and day to help make that escape possible, oftentimes carrying dirt from the tunnels in his pant legs to be spread outside when the Germans weren’t looking; or he would stand night watch as the diggers burrowed underground towards their intended escape.

In January of 1945, as the Russian troops closed in on Stalag Luft III, Hitler ordered all 11,000 POWs to be moved to prevent their capture. He intended to use them as gambits as his war crumbled around him. That death march was 60 miles, through the worst snow storm to hit Europe in 50 years. Dick Kenney was one of those men who marched through snow and ice, in sub-zero weather. As a result of injuries sustained in that march he received a second Purple Heart. Ironically, that second Purple Heart didn’t arrive until 68 years later, when his story surfaced in an article in the San Diego Union-Tribune.

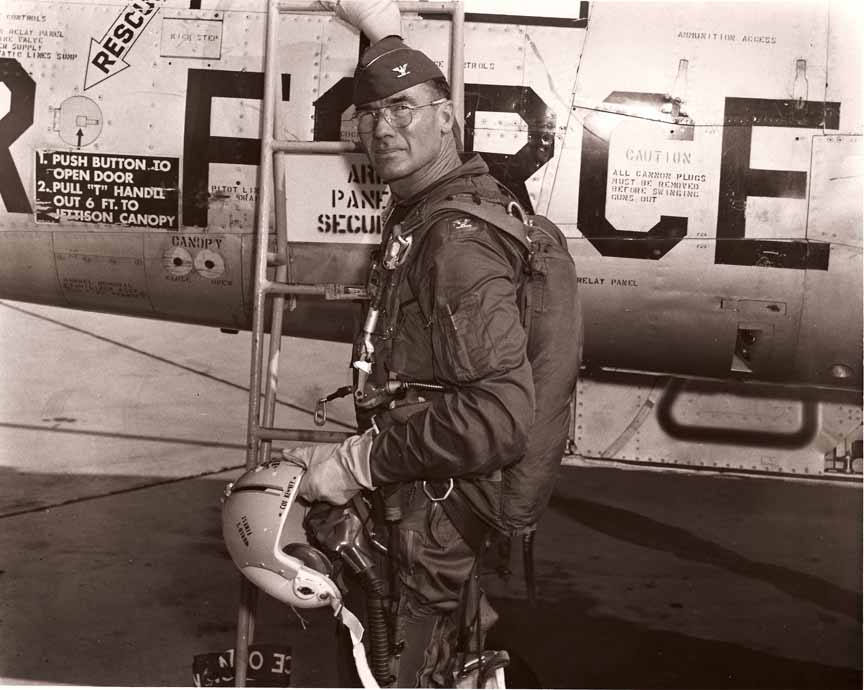

Dick Kenney flew in the Korean War, as squadron commander of a Saber jet outfit. He was crucial in instructing Navy fliers in the transition from prop to jet propulsion, and in particular regarding carrier landings. He also helped with the transition from propellors to jets with the Mexican Air Force as an emissary of the United States Air Force.

Dick Kenney went on to serve as an officer in the Army Air Corps (later the Air Force) for 27 years, logging 6,000 flight hours that covered two wars. “Flying was my life,” he often said proudly.

He became carrier qualified (unusual for an Air Force flier), and spent a year as a Navy flight instructor where he played a role in helping the Navy make the transition from propeller to jet aircraft.

Now a full Colonel, Dick Kenney is seen here climbing out of the cockpit of his F-100 Super Sabre. He had just completed 6,000 hours in the air.

He then went on to serve as emissary of the United States assigned to assist the Mexican Air Force in their transition into jets. He was presented with Mexican Wings and made an honorary member of their air force.

Colonel Kenney trained combat crews in aerial gunnery, bombing and strafing out of Nellis Air Force Base in mid-1953. In search of that elusive fifth kill to qualify him as an ace, Kenney signed up to fly in the Korean War, as squadron commander of a Saber jet outfit. The war, however, was all but ended, and so had his chances to achieve the title of “flying ace.”

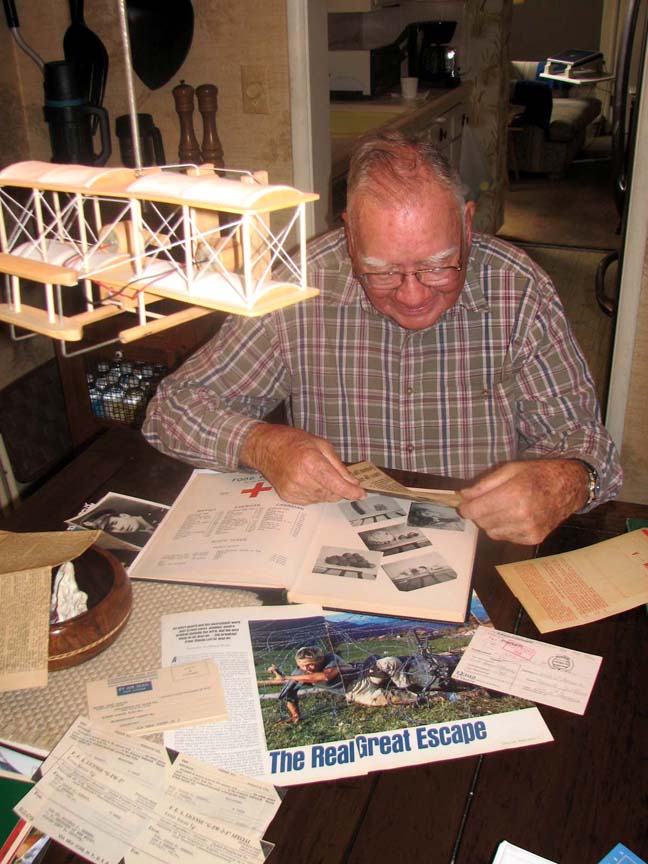

In his den, Colonel Dick Kenney is seen here inspecting some of his war memorabilia. Photo by Joe Ditler.

After the Korean War Kenney was assigned to the Pentagon and flew F-86s with the DC National Guard at Andrews Field, Maryland, Upon completion of this tour he was assigned to fly F-100s out of Foster Air Force Base in Victoria County, Texas until the base was closed in 1958.

“I loved that assignment,” recalled Kenney. “I worked for my former commanding officer in Korea and at Nellis, and the base was in the heart of some of the greatest hunting and fishing in Texas. As commander of a squadron it was good duty.”

Colonel Kenney being interviewed by KPBS TV show host, Noah Tafolla on a story about the shipwreck Monte Carlo. Dick and his brother were on this same site, January 1, 1937 when the floating gambling casino Monte Carlo crashed on Coronado Beach. Kenney recovered handfuls of silver dollars that day, many of which he later donated to the Coronado Historical Association. They are standing on the remains of the Monte Carlo. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Later on he was stationed at Misawa, in a remote portion of Japan. His squadron stood nuclear alert in Northern Japan where he helped them transfer from obsolete, straight winged F-84s to the Super Sabre F-100s.

Kenney returned for his second tour at the Pentagon and to flying F-100s with the DC National Guard. He was then assigned as advisor to the Sioux City National Guard where he was promoted to full Colonel. His final military assignment was at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina as deputy commander of operations for the 354th TAC Fighter Wing flying the familiar F-100 with a NATO commitment.

Colonel Dick Kenney giving a reporter the tour of his Wall of Glory, as he kiddingly referred to it as. Photo by Joe Ditler.

After retiring from the military Kenney co-owned the Nordic Ski Center in Squaw Valley, California. He was a member of the North Tahoe Search and Rescue Team, president of the Lake Tahoe Ski Club, an official for the United States Ski Association, as well as a Technical Delegate of the International Skying Federation. The ISF and the United States Ski Association honored Kenney in 1985 for his work and contributions to the sport.

Kenney was active in the ski industry until 1983 when he moved back to Coronado where he lived out the remainder of his life. Colonel Richard Kenney enjoyed his final years in Coronado, riding his bicycle and working on his 36-foot Grand Banks trawler that he would use to escape from the July Fourth crowds on Coronado.

Dick Kenney lived long enough to see almost all of his friends pass before him. He had, in his words, lived too long. “I expected to be pushing up poppies in World War II,” he often said. Here he is seen on the way to a Coronado Yacht Club function. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Kenney received a flurry of publicity late in life when he purchased and donated the 1923 Hotel del Coronado laundry truck to the Coronado Historical Association and Museum. During this time another small chapter from his youth surfaced and received attention in the print and television media.

Kenney and his brother were on Coronado Beach New Year’s Day, 1937, when the floating gambling casino Monte Carlo wrecked in the surf. They were among the many people who retrieved treasures from the abandoned ship. In Kenney’s case it was pocketfuls of silver dollars.

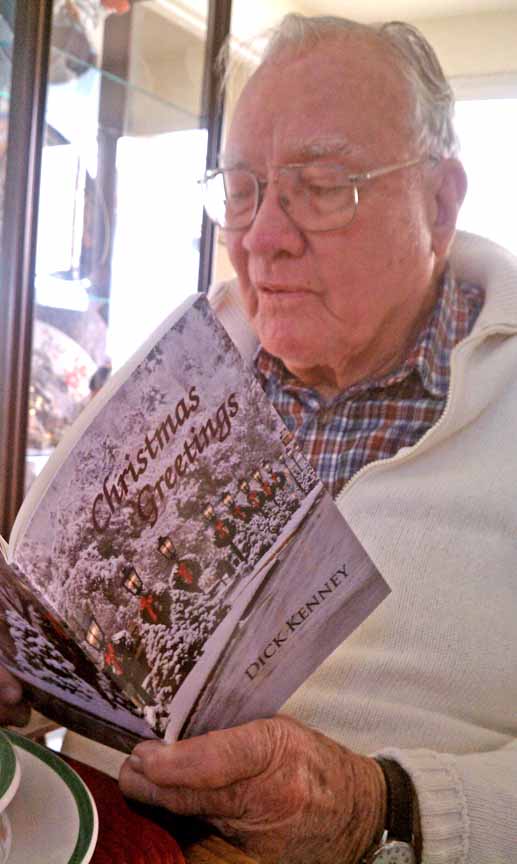

Dick Kenney wrote poetry all his life. Two years ago he published a book of his Christmas poems, which he would sometimes share with friends during the Christmas holidays. Seeing this sensitive side of such a great warrior was always a pleasant experience. Photo by Joe Ditler.

At his request, there will be no funeral services, however, friends have submitted his name for consideration on the Coronado Avenue of Heroes. Colonel Richard Kenney will be buried in the family plot at Fort Rosecrans. Donations in his memory are encouraged to the Coronado Yacht Club Junior Sailing Program. “That’s where I started, and that’s where I’d like it all to finish,” he said.

The media loved Dick Kenney. After World War II he seemed to be forgotten. But, in his 90s, he was featured in the San Diego Union-Tribune twice, on two TV news stations, the subject of two KPBS specials, and written about in local newspapers numerous times. Here he is seen walking to Shipwreck Beach with his close friend Dot Harms, three years ago, for an interview with KPBS reporter Ken Kramer about Kenney’s first hand recollections of the day the gambling casino Monte Carlo wrecked on Coronado’s beach. Photo by Joe Ditler.

Colonel Dick Kenney is survived by his his niece, Dorita Mickelsen of Coronado. The Colonel passed peacefully in his sleep the morning of December 11, at his Coronado home. He was 94, and had outlived them all.

Note: To view the TV 10 interview with Colonel Dick Kenney upon receiving his second Purple Heart (68 years late), visit the following link: