More delays have arisen in addressing the Tijuana sewage crisis.

On the US side of the border, overflow from wastewater treatment infrastructure marks a violation of the Clean Water Act, and the agency that operates it had until Aug. 15 to bring it into compliance.

“We’re not going to make the deadline,” said Maria-Elena Giner, commissioner for the International Boundary and Water Commission, which manages the plant. “But we do have a plan. There have been a lot of unforeseen challenges and things breaking down at our plant that were unexpected.”

Giner spoke the day before her deadline, giving an update on the ongoing projects to curb the 25 millions of gallons of sewage that flows into the ocean each day at a meeting of the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board.

The board was not happy.

“At the time, I had to talk myself into that generous timeline (of an Aug. 15 deadline),” said Celeste Cantú, the board’s chair. “I know it’s not lost on you, and I know how deeply you feel and how committed you are to being successful, but we find it really disheartening and outrageous, frankly.”

Cantú, as well as the rest of board, did not blame Giner. Instead, they praised her throughout the six-hour meeting, saying she was working to correct the mistakes of former commissioners.

But – the IBWC is still violating the Clean Water Act at a near-constant rate. Giner predicts a one-month delay in reaching compliance with the commission’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit.

Months ago, the IBWC was on track to meet its compliance deadline. In June, its levels were below the permit’s stipulations. What happened? Sediment, Giner said. This summer, an influx of sediment from Mexico has clogged the already struggling wastewater treatment infrastructure on the US side of the border.

At one point, so much sludge accumulated in the primary sedimentation tanks of the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant that tomatoes started to grow in them.

The Mexican government does not know where the unusually heavy flow of sediment is coming from, but it is working with the U.S. government to determine the scale and the source.

“We are not over the hump of finding the solution, because we are in the process of demonstrating the problem (to Mexico),” Giner said.

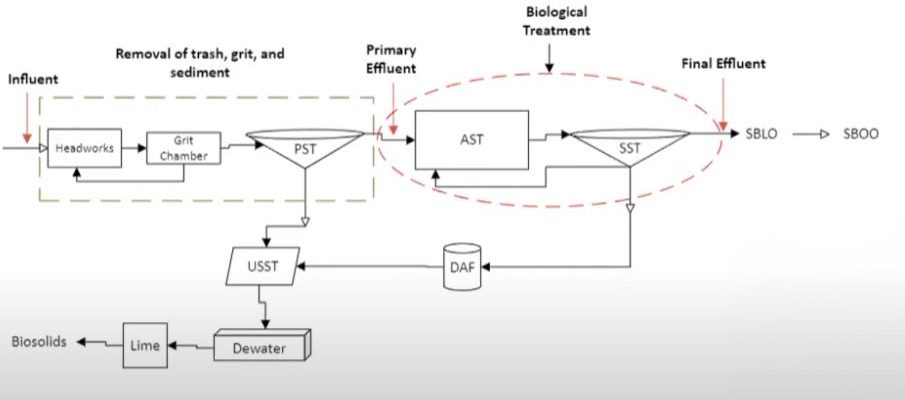

The sediment is clogging the front end of the treatment plant, said Dr. Gilbert Anaya, chief of the IBWC’s environmental services division. The plant works in stages: In a functional plant, solid material is filtered from influent waste before liquid waste is sent for biological treatment.

“We cleaned the influent channel, it filled up, and right away, it got filled with sediment,” Anaya said.

The sediment stalled progress the IBWC made toward reaching permit compliance. On June 7, the agency turned on a primary sedimentation tank. It jammed on June 10, and is now offline.

Then, on July 3, another tank was repaired and turned on. A chain snapped on July 16, likely due to the sediment, Giner said.

Currently, only one of of the five tanks is operable at the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant. Three should be running at all times, with the other two acting as redundancies in case of damage.

In a revised schedule, the IBWC predicts that one will begin to work again by Aug. 16, and two more in September. At that point, the IBWC should be back in compliance with its NPDES permit. The final tank is expected to be repaired in October.

The manifold problems with sewage infrastructure on both sides of the border interact with each other. One theory is that, as Mexico works to fix its own wastewater infrastructure problems, it inadvertently began to flood the SBIWTP with sediment. The South Bay plant receives wastewater from Mexico for processing.

Similarly, repairing the tanks again will push back the timeline for repairs to junction box one as a whole. It was previously slated for completion in February 2025, but is now delayed, with no projected completion date. Meanwhile, Mexico still needs to determine where the sediment is coming from and stop it.

Many local activists and politicians waited through the six-hour meeting to speak during public comment, including Imperial Beach Mayor Paloma Aguirre and Laura Wilkinson Sinton, who co-founded Stop the Sewage and is running for Coronado City Council.

“We ask you to use your authority, because even if someone is found guilty and pardoned, they are still made guilty by that act,” Wilkinson Sinton said. “I ask that you take the strongest fine you can possibly put (on the IBWC), and even though you can’t collect the fines, and even though they will be pardoned, it will send the message that you represent us as the people of california and the people of San Diego who are so drastically impacted by this. It will send that message you are on our side.”