Imperial Beach has been closed every day of 2023 due to sewage-contaminated water.

Imperial Beach has been closed every day of 2023 due to sewage-contaminated water.

Silver Strand Beach has been closed since February. And the Coronado shoreline joined the list of closures on May 5 and has been intermittently closed throughout the year.

The Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. International Boundary & Water Commission on Tuesday, May 9 hosted a public meeting to discuss the progress of projects planned to abate the problem. More than 140 people attended.

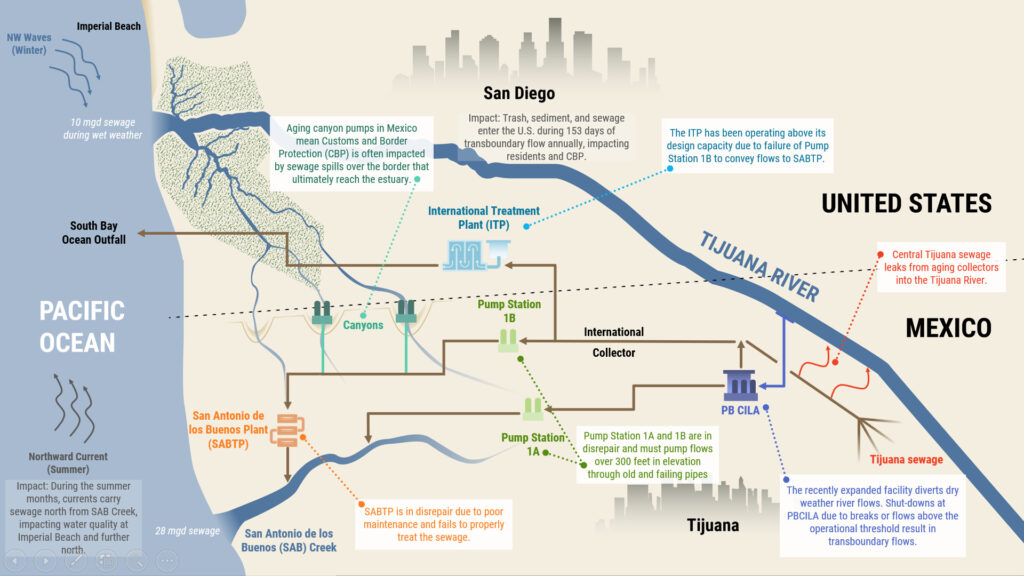

The closures arise as billions of gallons of sewage leak across the U.S.-Mexico border and into coastal waters. It’s a longstanding problem that was exacerbated by an unusually wet winter, but the Biden administration approved $300 million in this year’s budget to mitigate it. Mexico has slated an additional $144 million for the cause.

Although representatives at Wednesday’s meeting were unable to give a definitive date of beach reopenings, they did provide timelines for these projects.

The first, rehabilitation of the International Collector, will be completed by the end of May using $1 million in EPA funds and a $1 million match from Mexico.

“By rehabbing this pipeline, we will be reducing the risk of up to 7 million gallons of wastewater flow per day,” said Monica Moran, an environmental engineer for the EPA. “The International Collector is the largest wastewater pipeline in Tijuana.”

Much of the federal funding will be appropriated to the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant, eliminating the risk of 60 million gallons of sewage per day during rainstorms. Construction is projected to begin by the end of the year, and will take one to two years, according to IWBC documents.

Finally, the San Antonio de los Buenos Wastewater Treatment Plant, which lies about six miles south of the US-Mexico border and discharges sewage into the surf zone, will be mediated by Mexico. The project is expected to go out to bid this fall, and will take about two years to complete once construction begins.

“I want the public to know that this is steady progress that we’re making,” said Maria Elena Giner, Commissioner of the IWBC. “We do get a lot of questions from the public as to, ‘When, when, when, will we see results?’ And you are seeing results; you are seeing progress that’s incremental. Our goal is to open beaches. Our goal is to have that public amenity available to tourists and residents, and we do take that very seriously.”

Beach closures resulting from sewage leaks have become part of life along southern San Diego County shorelines. The issue arises when the Tijuana River experiences transboundary flow – water from Mexico is pushed from Tijuana across the border and into coastal waters. Most days, this movement is nonexistent, but with rain comes river flow. Major storm events, like those experienced this winter, exacerbate it.

The U.S. and Mexico in 2022 agreed on a cost-sharing agreement for sanitation at the border under Treaty Minute 328, an implementing agreement to the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

But the funding that has already been secured does not cover the full scope of solving the problem, though it does tackle some major contributors.

“A comprehensive solution is, unfortunately, going to far outstrip the funding that is available through the $300 million,” said Lily Lee, manager for the water infrastructure section of the EPA. “(During the 2021 planning phase), we expected it would probably take at least double that to fully address the problem of sewage flow. However, we heard very strongly from all of you in the public and stakeholders that we should plan ahead as if we were going to achieve the funding for this comprehensive solution.”

Part of the federal budget that allocated money toward these projects also included language allowing the EPA to transfer funds to the IWBC when needed to facilitate solutions, Lee said. But the law does not allow contributions of additional sources of funding toward the projects without Congressional approval, causing bureaucratic clog.

In an attempt to fix this, representatives introduced Assembly Bill 1597, which, if passed, would provide $50 million in state funding to the North American Development Bank’s general fund for cross-border water pollution projects.

Rehabilitation is long overdue, officials said, and while they have been aware of this for years, funding has been holding work back.

“Our construction budget is $25 million to $50 million annually, and we operate two of the nation’s largest dams,” Giner said, noting that the IWBC had never before received a direct appropriation for capital improvements. “We also have two wastewater treatment plants, 100 miles of levies, power plants, and ports of entry and monuments we’re trying to manage.”

In the design phase, officials are considering future deterioration of sewage treatment facilities in a more comprehensive way by appropriating operational and maintenance expenses into the plan. The EPA is using flood modeling to ensure new and rehabilitated facilities can withstand future rain and flooding events.

“The question is, ‘How do we get in front of these (issues with infrastructure) before they deteriorate?’” Giner said. To avoid this in the future, a chief part of the design/build contracts for remediation includes an asset management plan that appropriates money needed to operate.

“We are trying to do things correctly in the future,” Giner said.

Editor’s Note: updated 5/11/23 with the addition of a schematic map of the Tijuana wastewater and river flow

RELATED, 2022:

EPA Update on Tijuana Sewage Proposed Solutions – Public Comments Accepted Through August 1