“They say there’s an underground river

That none of us can see

And it flows through winding tunnels

On its way to a tideless sea.”

–Sting

As one rain storm after another bashes little Coronado, one can’t help but wonder where all that water goes. Certainly much of it finds its way into the bay and ocean. Street drains eagerly gulp down what they can, and you can almost hear the soil slurping it up in the wake of our recent dry spells.

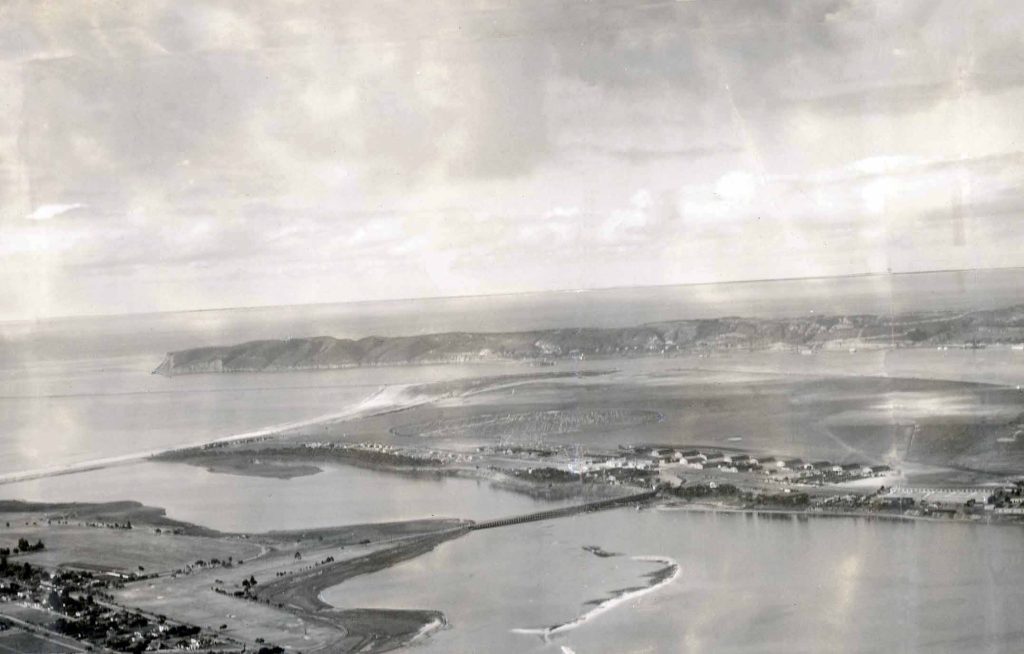

At times the Silver Strand closes, as bay and ocean temporarily connect, giving us the title of “island” for a while, and that’s just what we can see with our own eyes. What takes place under the surface of Coronado is an entirely different story, and might be interesting fodder for the likes of a modern day science fiction writer; a modern day Jules Verne.

Since the dawn of time man has drawn water from the ground. In Coronado that water flows from an underground source dating back to prehistoric times.

Richard Henry Dana, in his book “Two Years Before the Mast,” wrote of rowing across the channel in 1835, and into Whaler’s Bight, an inlet on North Coronado Island, to get drinking water.

Coastal Kumeyaay Indians hunted on Coronado seasonally, relying on potable water from the ground. Kumeyaay were reported at that same well, as late as 1914.

While all but forgotten in this day and age, that fresh water well still exists at what is now the intersection of runways 29 and 36 on Coronado’s North Island.

The late Joe Jessop, who spent his youth in Coronado (1900-1928) often spoke of his hunting for rabbits and drawing water from that well. Early pilots planted shrubbery and trees there to make the hole in the ground visible to other fliers in limited visibility conditions, said Jessop.

The trees proved to be a flight hazard as well, however, and were eventually removed. Today concrete riprap marks the well, and only an old painting of Jessop’s survives to show what the oasis looked like. Whaler’s Bight was long ago filled in, but can be seen on early maps of North Island.

Another fresh water well existed where the Coronado Cays is built today. Whaling ships anchored off the Silver Strand and watered from this well as early as the 1780s.

In the early 1800s a young Russian girl was found shipwrecked there. The well has been known ever since as Russian Springs to those familiar with Coronado history. Today several homes are built over it. Residents complain their yards and foundations are perpetually wet. Plumbers just shake their heads.

The late Colonel Richard Kenney recalled the property on Third Street between F and G Avenue had a constant stream of water seeping from the ground.

“There was a car repair garage at the top of the hill back then,” said Kenney. “As kids, we would play in that neighborhood. Fresh water came right out of the ground and trickled down the street in a steady flow,” he said.

This is known as the high ground of Coronado. It was also a place where Kumeyaay built their camps. Records indicate as many as six Kumeyaay families still lived in brush dwellings along this street in 1904, when the local merchants forcibly relocated them to Mesa Grande. As a sign of the times, Coronado businessmen campaigned that Indians were bad for Coronado tourism.

Through the years legend and lore have mixed with history and fact to create a loosely woven romantic tale of things like an underground river, buried treasure, a subterranean cavern, Indian burial grounds and even a fountain of youth.

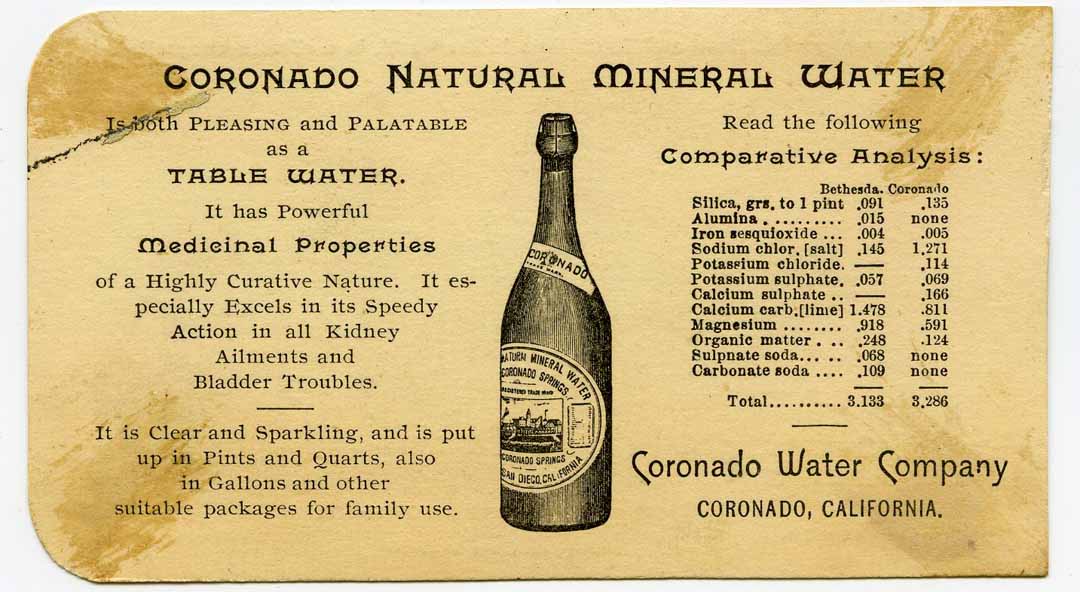

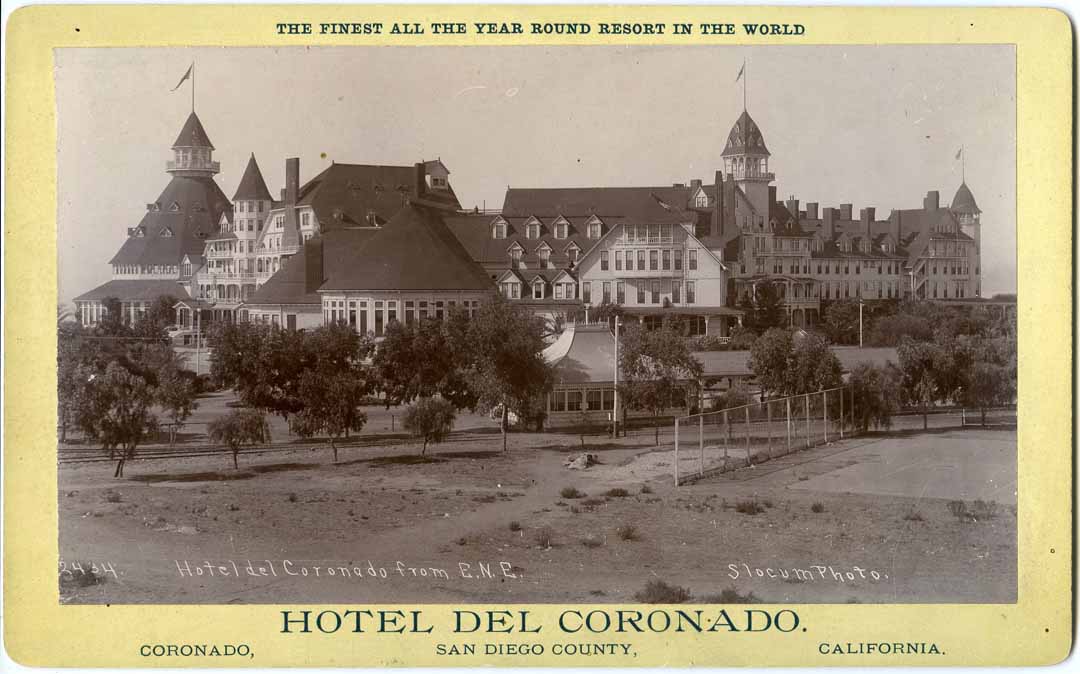

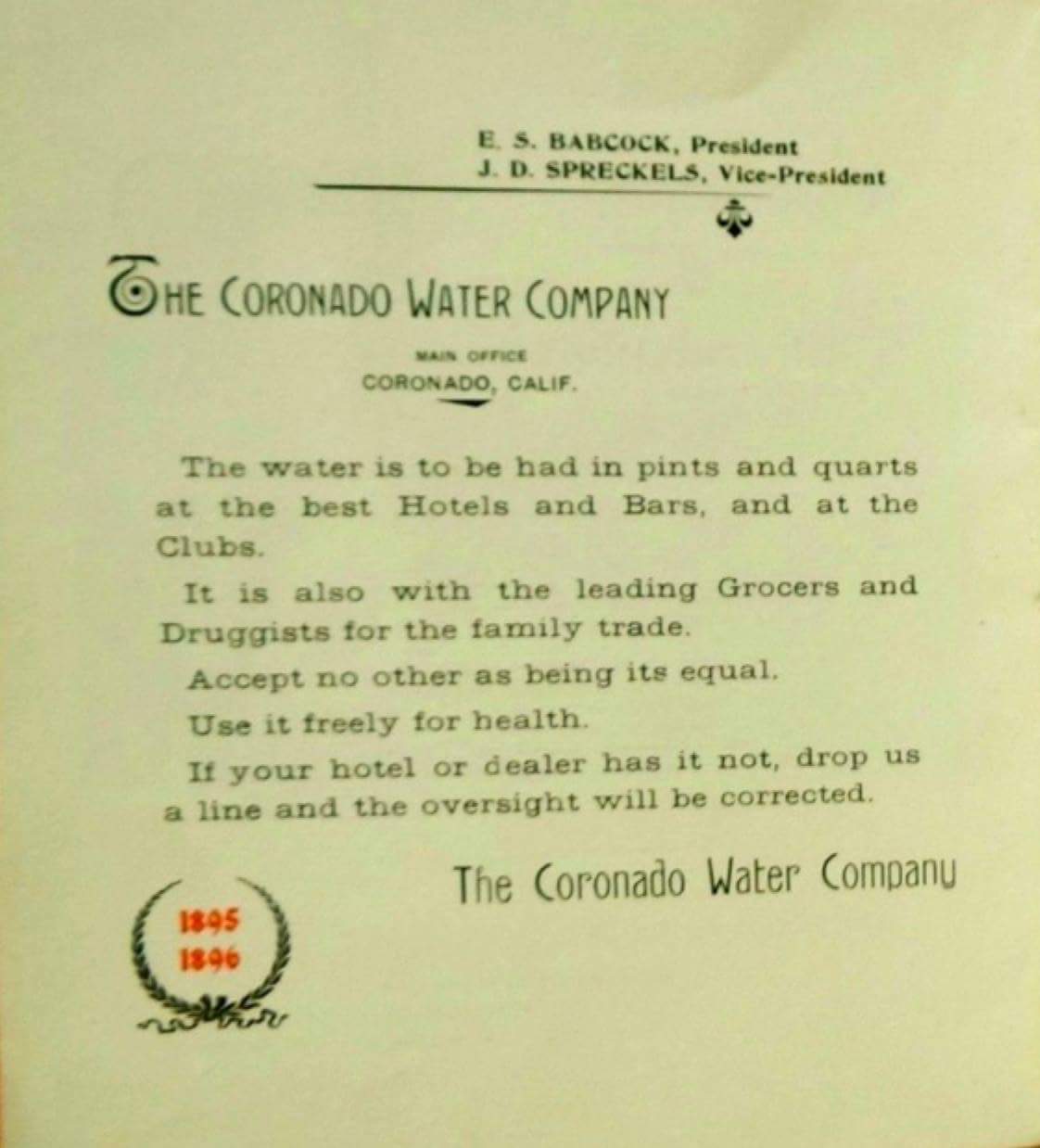

The Hotel del Coronado was quick to market Coronado water. The advertisement from the 1880s read:

“The Famous Coronado Water, Which has established such an excellent reputation for its amazingly quick and curative action on the kidneys and bladder, is the only water used at the hotel.”

The late Richard Pourade of San Diego, a writer and historian, wrote, “The Fountain of Youth that had eluded Ponce de Leon in Florida perhaps was in Southern California all the time!”

The Coronado river is actually an aquifer. Geologists refer to this large current of water as the San Diego Formation. It runs from the 805 Freeway in the east to just west (offshore) of Coronado. It runs to Old Town in the north and the Mexican border in the south.

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing rock, gravel, sand, silt or clay from which groundwater can be extracted through the use of wells and pumps.

“The water from the San Diego Formation has been tested and it is ancient,” said Mark Rogers, former operations director for the Sweetwater Authority that feeds most of San Diego its water.

“We’ve dated that water at 15,000-20,000 years old,” he said.

In Coronado dozens of residents pump groundwater and use it to water their yards with minimal saltwater intrusion. Most don’t wish to go on record, for fear the City will create a water tax. Meanwhile, new construction by at least some home builders on the island offer to sink a well for their clients, for a price.

Again, no one wants to be quoted or go on record for this. A homeowner on G Avenue was proud of his success pumping groundwater, but insisted on anonymity. He uses it to fill his swimming pool. He uses an additive to make sure the water is safe for swimming. In general, the groundwater is potable but not especially tasty. It’s bitter.

Another theory is that the water comes north along the Silver Strand via an ancient caldera – an elongated lava tube created by volcanic collapse centuries ago, suggesting the high ground at Third Street and F Avenue might have been a volcanic vent hole back then, or the result of a great bubble of lava rising to the surface.

Hundreds of wells have been dug in the San Diego area. Even the Coronado Golf Course did some test well boring, looking for fresh water. Hired geologists couldn’t find water clear enough to put on the golf course greens despite drilling several hundred feet.

While ground water seems to run deep in the Flats (the low-lying area surrounding the golf course), homes in the Country Club area were wet at or near the surface.

“When I crawl under these homes the soil is muddy and there is mildew under the structures,” said Glen Shirer, a former plumber on the island.

Jim Newhall, a longtime Coronado resident, ran into aggressive groundwater while building a foundation for his home in the 600 block of J Avenue.

“We needed to dig 10 feet for my basement,” said Newhall. “We hit water at eight feet, which required me to bring in a dewatering company to sink a well pump. We pumped out surrounding water for three months before we could continue construction.”

Newhall said that they eventually had to sink beams for his foundation 30 feet into the soil. Mud retrieved at that depth contained ancient clamshells. He speculates that maybe 500, or even 5,000 years ago, his property could have been beachfront, or a Kumeyaay site. Or, the shells could have just been passengers along the underground river.

Part of me admires the imaginative way some residents have benefitted from this free water source. But as the county continues to experience water shortage, no one should be too surprised if the city of Coronado looked into water reclamation options, or at least monitored underground water levels and kept a record of who is drawing from the aquifer.

We, as a species, continue to abuse our natural resources. In theory, abuse of the aquifer waters could create sink holes across the island. Currently, that is not the case.

It’s not illegal to drill a well on private property, but it’s extremely costly. Well history throughout San Diego seems to offer only one axiom, and that is that the underground water, whether fresh or saltwater, mingles, causing each well to suffer extreme variances in quantity and quality from year to year, month to month.

Old legends are hard to dispel. The Kumeyaay have no specific records concerning fresh water on Coronado, but in 1888 the San Diego Union ran an article entitled, “The Bowels of the Earth: Discovery of an Immense Subterranean Cavern in San Diego.”

One can imagine the hubbub this caused in the county. The 6,500-word article went on to describe how scientists had found “a prehistoric race entombed in coffins chiseled out of solid stone,” and “a cave of crystals under the bed of San Diego Bay.” Shades of Indiana Jones.

It wasn’t long before people began to ask questions. A retraction was soon printed in the paper and the reporter was never heard from again. The lore of a secret, underground river, however, continues to feed our imagination more than a century later; now, perhaps, more out of necessity than of curiosity.

For more Coronado history, visit the Coronado Historical Association.