CORONADO’S STAN ABELE

“I remember looking at my watch at 5 p.m. and thinking it would be dark soon and we would be goners once the sharks found us.”

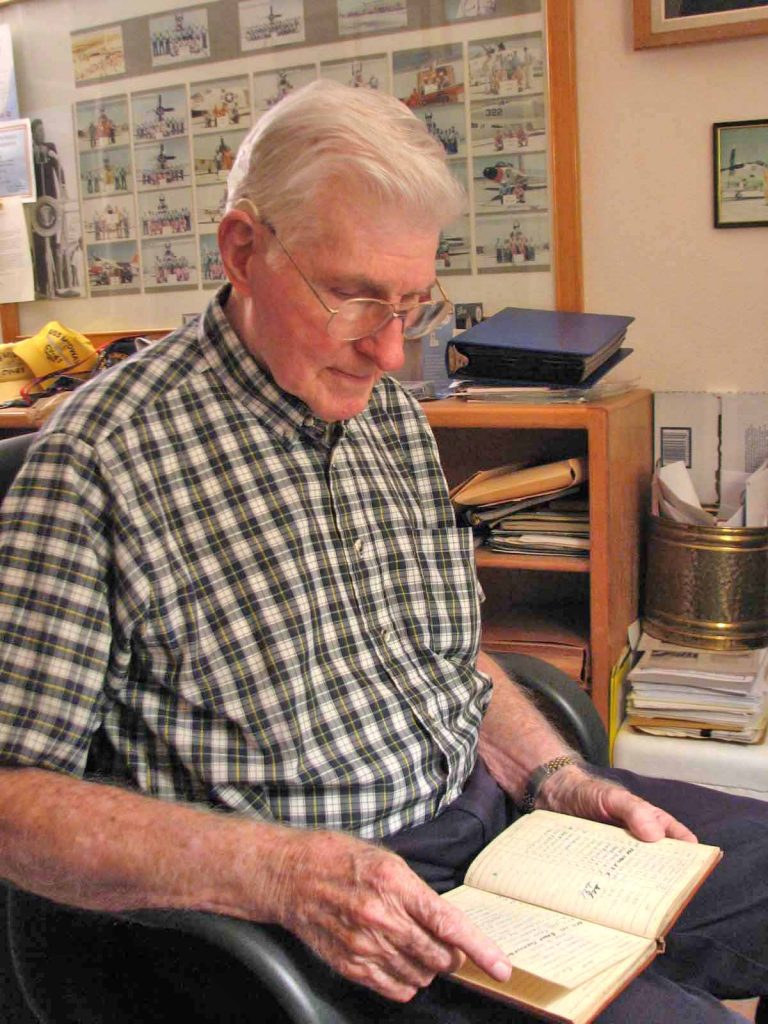

Longtime Coronado resident Stanley Abele passed away October 21 following a brief illness. He was a celebrated World War II pilot and survivor of Kamikaze attacks on the USS Bunker Hill that left him adrift in the Pacific Ocean. He lived between Alpine and Coronado in his final years, and volunteered on the USS Midway Aircraft Carrier Museum right up until his death. He was 97.

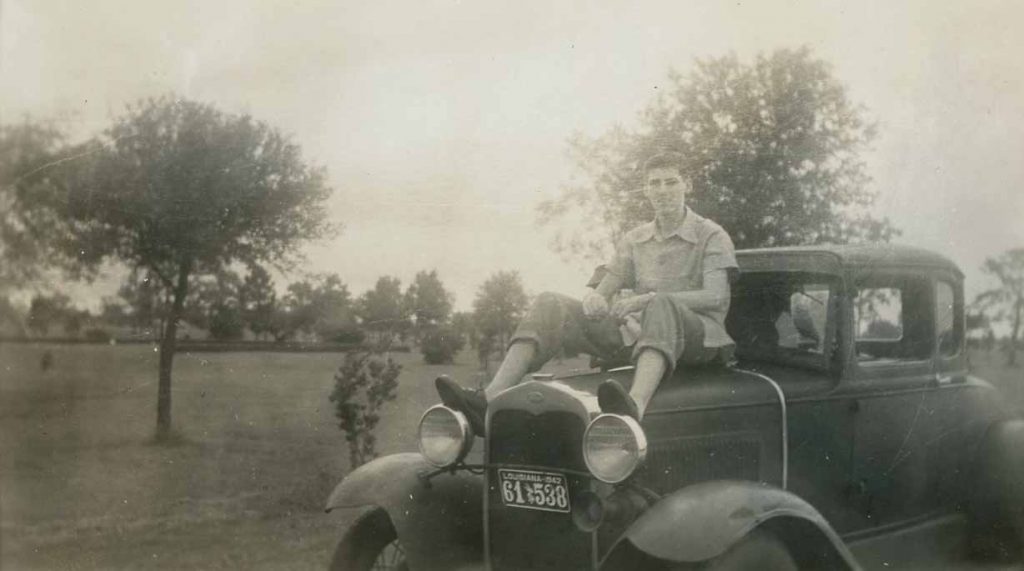

Stanley Frederick Abele was born in New Orleans June 28, 1922 as the younger of two brothers to John Andrew Abele and Elizabeth Bentel. His maternal and paternal grandparents were German immigrants.

Stan graduated from Samuel J. Peters Boys’ Commercial High School in New Orleans, and attended five semesters at Tulane University. He was a veteran of 24 years in the US Navy and recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, three Air Medals, Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Unit Commendation, Asiatic/Pacific and Vietnam Unit Citations, a Korean Service Medal, and others. He was also honored along Coronado’s Avenue of Heroes in 2017.

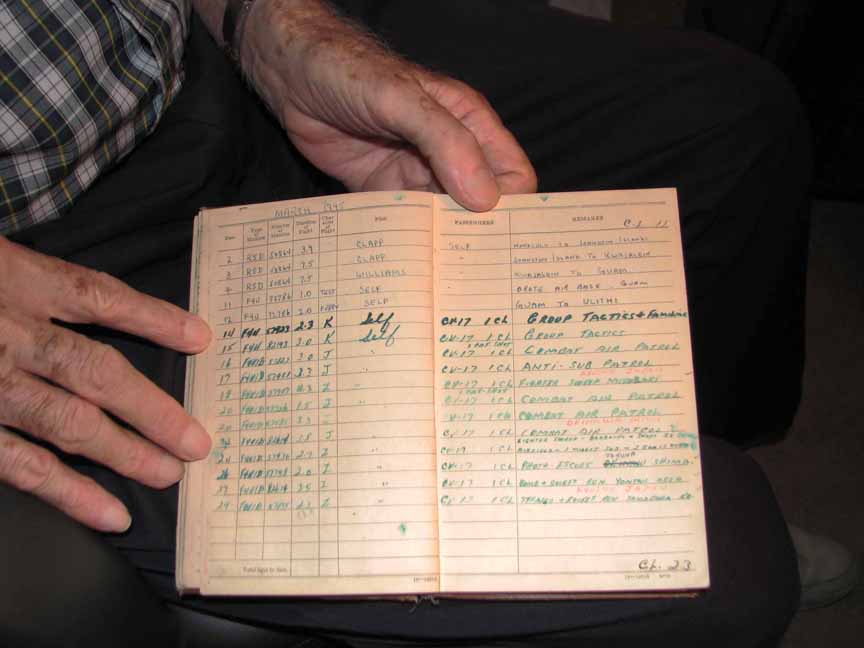

Stan Abele performed more than 60 combat missions but records exist for only 20 because most of his paperwork was destroyed when the Bunker Hill was attacked.

In addition to his Kamikaze kill, Stan sank a miniature Japanese submarine. He also destroyed several enemy airfields and dozens of planes on the ground. He destroyed enemy barracks and shops, industrial complexes, boats, photo escort planes, provided air cover for our troops on dangerous beachheads and anything else that his orders dictated, in an effort to bring that war to a close. Typically, Stan’s missions ran two-to-six hours each.

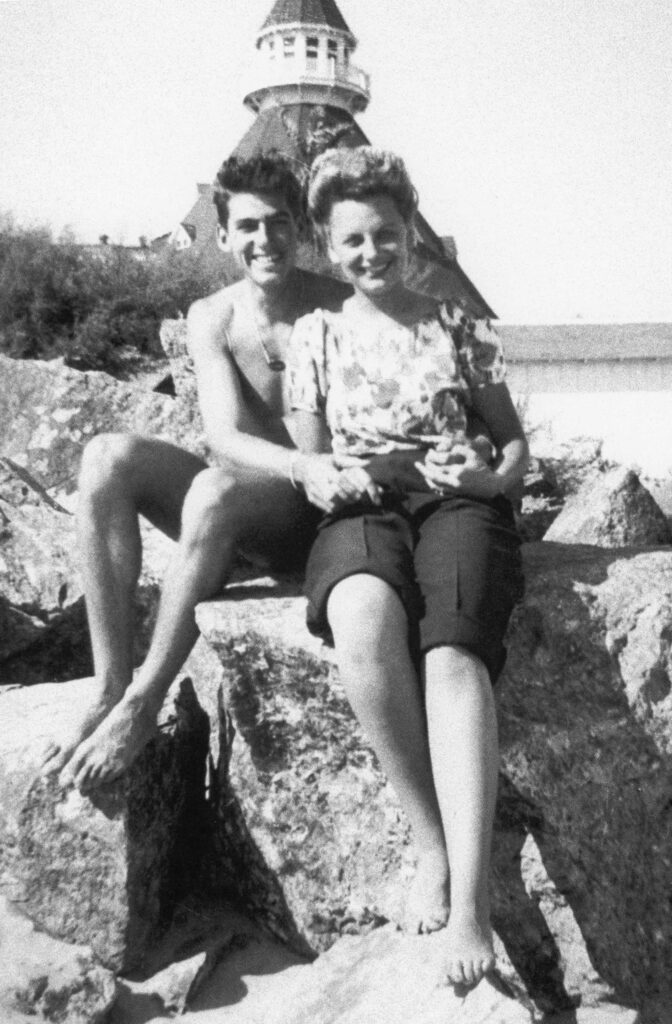

Stan’s story began on New Year’s Eve, 1944, three years after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Then-Ensign Stan Abele was billeted at the Hotel del Coronado with his Navy buddies for six months of flight training.

Obviously, the living arrangements were off the charts in elegance and décor. At that time the Del was also the place to be for single women looking to catch a young pilot – a popular pursuit in the early years of World War II. Old black & white photos are all that survive those days.

The photographs capture them in their pressed uniforms standing in the hotel’s courtyard or at a dining table surrounded by women and a spacious dance floor. Those were the good times. Within a year, however, Stan would be one of the only survivors from those small and rumpled images.

Stan and his ensign buddies were shipped off to Hawaii to fight the war in the Pacific. They had been training for what seemed like forever in stateside duties. As a child all Stan ever wanted to do was fly. There wasn’t a military aircraft he didn’t know how to fly. Still, they waited for weeks and months in slow-moving pilot pools for their names to be called for assignment to the front lines.

Finally, Stan and his team were called on to deliver five new Corsairs to the island airstrip of Ulithi – a place that measured but a mile long and a half-mile wide on the map. After they had delivered the planes, the impatient young pilots found a landing craft tied to a pier. They got it started and headed out into the anchorage where about 100 ships were sitting in the lagoon.

“We were working without orders at that point, and on our own initiative,” said Stan, falling just short of admitting to being AWOL (absent without leave), “but we were getting closer to the war.”

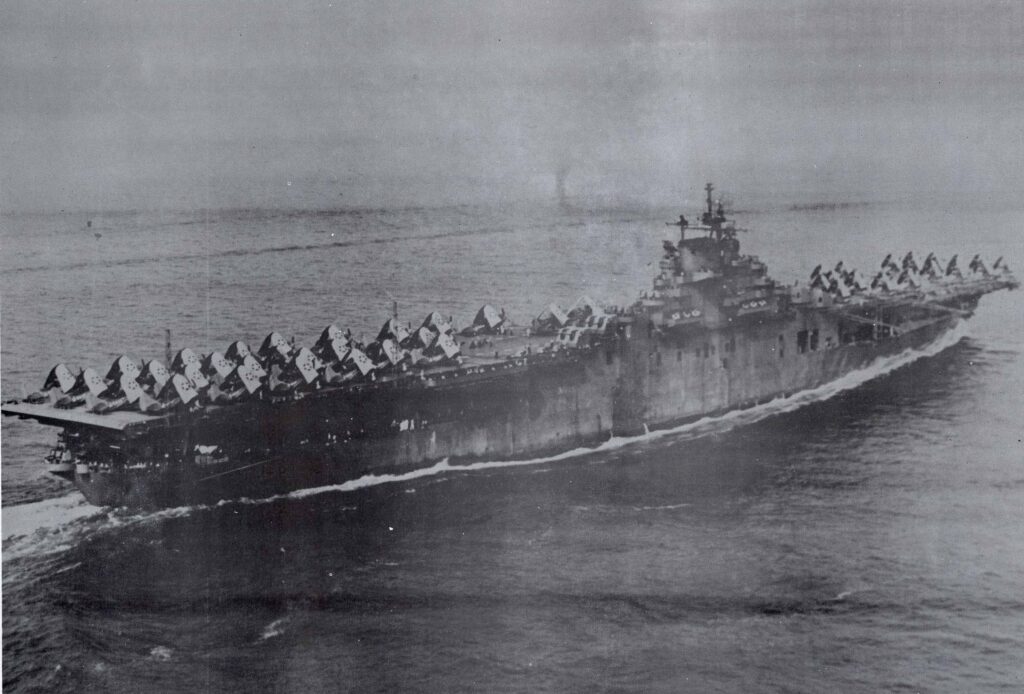

They went from ship to ship until they found the aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill, flagship of the fleet. They went up the accommodation ladder and set their stolen landing craft adrift. When asked where their orders were, they just shook their heads and said, “They are coming.”

After some serious questioning from Admiral Mitscher about a mysterious landing craft found adrift in the lagoon, the five were mustered into the flight crews of the Bunker Hill. And that was how Stan Abele got into the war in January 1945.

Stan flew numerous missions under Admiral Mitscher’s command during the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Although he did shoot down one Japanese Kamikaze plane, most of his work involved offering support to landing troops on the many nearby islands and flying combat air patrol for the destroyer picket groups spread out over a 150-mile radius. At that stage of the war aerial dogfights in the Pacific were coming to a close as Japan focused their efforts on the one-way ticketed Kamikaze attacks.

Four months later, however, the young American pilots would be caught up in one of the greatest US Naval catastrophes of the war – the Kamikaze attack of the aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill, underway with her task force between Okinawa and Japan.

Stan survived, his friends did not.

On May 11 Stan and other pilots had just had an exciting briefing where their shipmates described how they had shot down two Kamikaze planes and sank several ships. Many of the pilots lingered drinking coffee in the ready room. Stan, who didn’t drink coffee, headed topsides in readiness for his flight. He was on the flight deck of the Bunker Hill putting on his parachute when he heard an airplane flying in close.

“At first I thought it was one of ours and I was worried he would get shot down,” said Stan. “Then I realized it wasn’t and yelled, ‘IT’S A JAP!’ but it was too late. He clipped the upraised wings of my plane and crashed into the four other planes next to me on the fantail, destroying every one of them and killing the pilots inside. The entire flight deck of the USS Bunker Hill was filled with bombers, fighter planes and torpedo planes, all loaded and ready for takeoff into battle.

A second Kamikaze hit 30 seconds later and its bomb blew up killing everyone in the ready room amidships (where Stan had just left). Everywhere planes were exploding. Rockets and munitions on the surprised American planes were detonating and the entire flight deck and island (command center) of the carrier were on fire. It was a raging inferno, a flaming holocaust. Worse, the stench of burning fuel and human flesh filled the air.

In an effort to get away from the fires and exploding munitions, Stan and his mechanic went out onto the catwalk of the ship that extended from the fantail along the side. Soon, 15 or 20 other survivors joined them. Every hatchway they attempted to open accosted them with toxic fire and billowing smoke.

Most of the dead, it was later determined, died from smoke inhalation.

“We kept thinking someone was going to rescue us, but it didn’t happen,” recalled Stan. The attack took place about 10 a.m. and by noon they could no longer breathe on the catwalk. Some of the men took to urinating on their neck scarves, covering their faces with the wet fabric, but even that didn’t help.

Out of desperation the stranded pilots and mechanics jumped overboard, landing 60 feet below in the cold Pacific Ocean only to watch as their battered and burning ship steamed on.

“Funny what you remember at times like that,” said Stan. “I remember losing a shoe when I hit the water. I remember being angry at being left out there in the ocean. And I remember looking at my watch at 5 p.m. and thinking it would be dark soon and we would be goners once the sharks found us. The task force was nowhere to be seen. The Bunker Hill kept steaming on at 20 knots and now we could barely see her smoke on the horizon.”

All he could do was engage his bright yellow shark repellent and hope that it worked. The yellow dye filled the water around them like a giant oil slick.

After five hours in the water shock began to set in. Then, when all hope seemed lost, the men rose to the crest of a swell and sighted the mast of a destroyer. It had been working its way back along the carrier’s wake and picking up survivors. Just as darkness set in, sailors from the destroyer, hanging from a large cargo net draped over the side, pulled Stan and the others from the ocean.

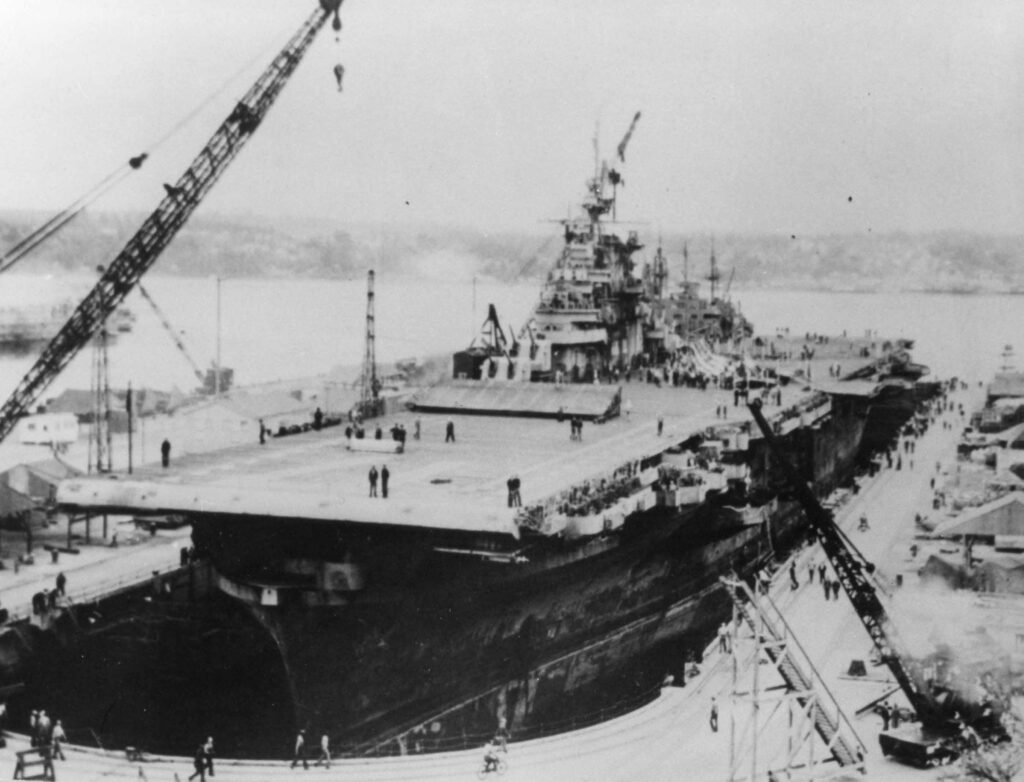

The next day Stan and the other men were conveyed by hi-line to the badly damaged Bunker Hill, as a multitude of wounded were transferred the other direction for medical aid.

Amazingly, within 24 hours, all fires had been extinguished on the carrier. At one point the water had built up on the hanger deck to such an extent that it threatened the stability of the ship. The captain got on the horn and told everyone to hang on as he put the ship hard over to starboard and all the water went over the port side – an unorthodox maneuver, but one that probably saved the ship.

“When I came back on board, I wasn’t prepared for what I saw,” remembered Stan. “The hanger deck had hundreds of dead bodies on it covered with canvas tarps. They were being readied for burial at sea. A tractor was pushing wrecked airplanes over the side.”

Greeting the returning pilots and sailors was a mass of charred and twisted wreckage. The wooden flight deck was unrecognizable. “I tried to find my best friend, Gene Powell, and went from body to body before I just couldn’t take it anymore,” said Stan. “I lifted up one tarp and the poor fellow was so badly burned that his arm fell off.

“Gene had been in the ready room during the attack. He was on the previous flight and shot down a Kamikaze. I remember saying to him, ‘I’m going to get one too, you hear?’” That was the last time Stan saw his best friend. He never found Gene’s body but his name is listed among the casualties from that tragic day when 392 died (or went missing) and another 264 were wounded.

The attack on the Bunker Hill became one of the greatest US Naval disasters a ship was ever to survive. And yet, during her brief WWII Pacific campaign, the USS Bunker Hill and her pilots were responsible for shooting down 475 Japanese planes.

Stan joined other survivors in collecting personal effects of their fallen comrades, sorting through them, and writing letters to loved ones – many of whom Stan knew quite well. From his flooded and charred quarters, he sat down and put pen to paper in that most painful of tasks.

The days that followed were a blur for most of the survivors of the May 11, 1945 attack. The fire had destroyed most of the food on board the Bunker Hill, but Stan remembered clearly the menu during those tough days:

“For breakfast we had powdered eggs and Spam. For lunch we had a Spam sandwich. For dinner we had Spam steak. Fortunately, I like Spam, but I still can’t stand coffee.”

Somehow the Bunker Hill reached Pearl Harbor under her own power. Stan’s recollections of his long life and WWII were precise in every way. Even more so when he recalled the food they received when reaching Pearl Harbor:

“We got to Pearl and they gave us fresh milk. Oh boy! Ice cream. Wow! Fruit. Oh Boy! Eggs. Phew! We gorged on food for a couple of days while the ship re-provisioned. Then we headed for Bremerton, WA, for major repairs.”

The Bunker Hill was repaired in four months and went on to help evacuate troops and equipment after the war (in the 1960s, the ship was tied up at North Island Naval Air Station). For Stan it meant shore duty and a transfer to Landing Signal Officers’ School in Jacksonville, Florida, where he continued to fly everything and anything he could. In 1948 he decided to settle down. He married Ethel Combs and they moved to the West Coast.

During the Korean Conflict Stan worked as assistant communications officer encoding and decoding thousands of wartime messages for the top brass. He had one of the highest security clearances available and was invaluable to his command. As a child he learned to type quickly and correctly. This one talent served him throughout his long military career.

In 1966, during the Vietnam War, Stan served on the aircraft carriers USS Kitty Hawk and USS Ranger. It was during this time he received word his wife had lost their baby in childbirth. He put in for immediate retirement and after 24 years in the Navy retired as a commander. Stan and his wife bought a 26-foot trailer and toured the country for months on a belated honeymoon, towing their trailer everywhere they went. The love of his life died in 1986 after a long fight with colon cancer. They had no children.

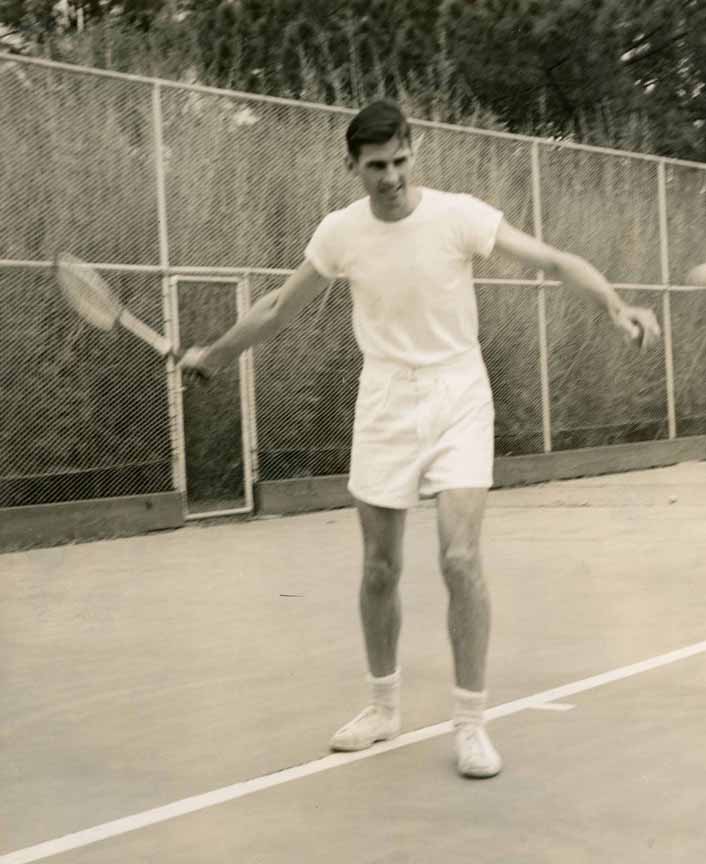

Like most American kids, Stan had banged a few tennis balls around during the Great Depression. Over the years he began to perfect his gangly movement and his self-taught strokes. Now, as a young adult, he had turned himself into quite a tennis player, playing (and winning) many singles and doubles tournaments in his off time. The United States Professional Tennis Association ranked Stan and his doubles partner as the second-best team in the Southeastern United States.

In his later years, Stan played in highly competitive pick-up matches at the Hotel del Coronado. Often, he would exchange shots with players like former champion Pam Shriver, and local doubles strategists Dale Curtis, Bob Brady, Gil Roesch and Ed Fury. It was always a lively match, held on Court 4 (the stadium court) where an audience would frequently gather to applaud the highly competitive tennis.

Throughout his long life, Stan Abele had been involved with and supported such groups as the Disabled American Veterans (he lost much of his hearing as a combat pilot), American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Tailhook Association, and the USO (United Service Organizations).

Stan’s experiences in World War II made him an authority on aircraft carriers and WWII. He put in time every week at the Midway Aircraft Carrier Museum as a volunteer docent. He thrilled his audiences with first-hand accounts of the tragic attack on the USS Bunker Hill, sharing with visitors his vivid descriptions of life on an aircraft carrier in time of war.

Stanley Frederick Abele is survived by his longtime and loving companion of 32 years, Sue Steel of Coronado, and his nephew Rodney John Abele (Linda) of New Orleans. Great nephews Rodney Abele III of Washington, DC and Andrew Abele of New Orleans also survive him.

Memorial services and a funeral mass took place at North Island Chapel October 24. Internment will take place at Miramar in November, the exact date has yet to be announced.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made “In Memory of Stanley Abele,” to the Midway Museum Foundation, c/o the Midway Museum, 910 N. Harbor Drive, San Diego, CA 92101.

–Joe Ditler

[Author’s Note: Stan Abele’s days at the Hotel Del were documented Oct. 29 in Diane Bell’s column in the San Diego Union-Tribune. That piece can be seen at: https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/columnists/story/2019-10-29/coronado-war-hero-leaves-a-romantic-legacy?fbclid=IwAR2k8d6l3AHz0WQSASAfdO428ruI1Fwo5ilTm9MDd0gG3phcKT2g6GE-3ow]

[Second Author’s Note: Footage of the Kamikaze attack on Bunker Hill (at 5-minute mark) can be seen at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3Ryyek9GEQ]

Joe Ditler, who interviewed Stan Abele and wrote this tribute, owns and operates “Coronado Storyteller.” Ditler is a published writer and author, publicist and historian. He offers his services in writing these “living obituaries” so as to capture stories like Stan Abele’s, both for history and posterity, while they can still tell their story; and to relieve that burden from families at the time of death. Ditler has done dozens and dozens of them on Coronado’s heralded members of the Greatest Generation.

For more information, contact him directly at: [email protected]