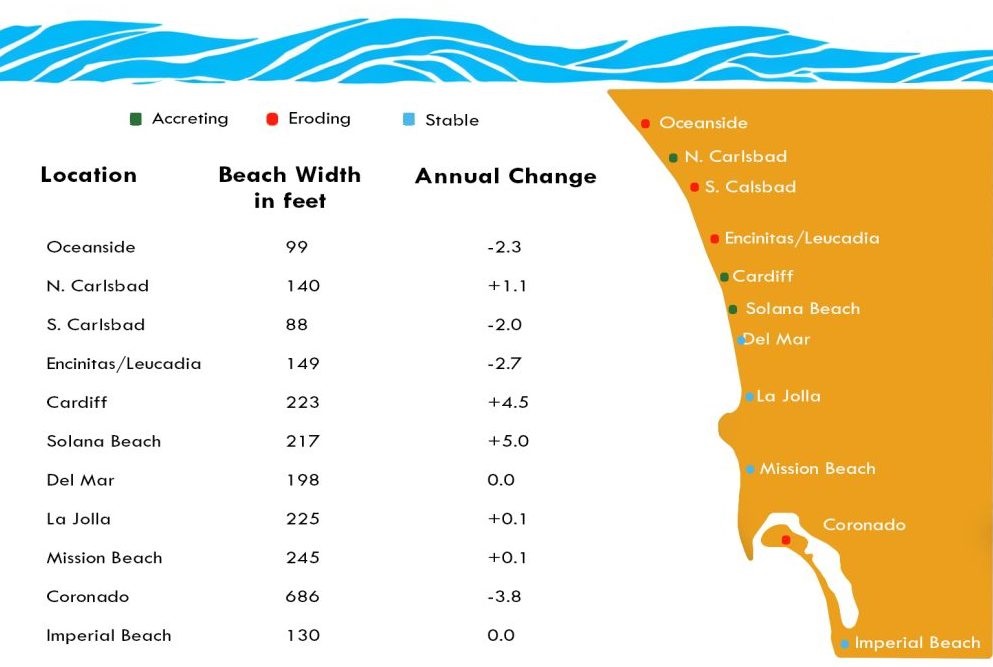

Coronado has lost about 81 feet of beach over the last 22 years, and it’s eroding at the fastest rate in San Diego County, according to a report released by the San Diego Association of Governments.

But it’s also the county’s widest beach, stretching 686 feet and dwarfing the rest, whose average width sits at 218 feet. Both Oceanside and South Carlsbad have beach widths of fewer than 100 feet.

The numbers are not cause for concern, at least not yet, said Coronado City Council member Mike Donovan, who also sits on SANDAG’s Shoreline Preservation Working Group. The county is currently planning a feasibility study for its third round of sand replenishment projects to slow coastal erosion.

Two similar beach replenishment projects have been undertaken since 2000, although neither of them provided sand to Coronado specifically. The first, in 2001, cost $18 million, and the second, in 2011, cost $26 million. Both were funded largely by federal and state grants.

Coronado has contributed about $15,000 to SANDAG for the feasibility study for San Diego County’s next nourishment project, Donovan said, and a contractor is expected to be selected by the end of the year.

“An area which is more worrisome is beach erosion along our bay-side coastline,” Donovan said. “In particular, Grand Caribe Isle in the Coronado Cays and along First Street in the Village.”

At Donovan’s request, bayside beaches – a feature unique to Coronado’s geography – will be included in the upcoming feasibility study.

Shoreline erosion is a concern for all coastal communities. It’s a natural part of beaches’ sand cycles, in which winter weather erodes sand that is later deposited elsewhere in the summer, that is exacerbated by human development and rising sea levels.

A problem arises when erosion meets coastal structures. In effort to preserve buildings and infrastructure, shoreline armoring, such as seawalls and jetties, can slow coastal erosion in their immediate areas. But they ultimately speed erosion on other beaches by disrupting the natural cycle of sand migration that allows beaches to ebb and flow, effectively pushing the problem further and further along the coast.

Armoring also prevents the natural erosion of coastal cliffs and rocks that creates new sand, and jetties can trap sand, causing further beach loss, but the need to protect coastal communities yields a series of temporary solutions that may compound the problem.

A third of Southern California’s coastline is armored, according to a 2015 Stanford University report. About 80 percent of California’s shoreline is actively eroding, the report finds.

The California Coastal Commission allows armoring where coastal development needs protection, but otherwise discourages their installation in effort to slow erosion. This is not unique to California, and many states turn to sand replenishment projects to save their beaches.

Just as shoreline armoring carries unintended consequences, sand replenishment can as well. But for now, it’s the preferred solution.

“Until we find an alternate solution for maintaining beaches along the coastline of our cities, I support some type of beach sand replenishment,” Donovan said. “Our entire county benefits from our great beaches, not only from the recreational standpoint, but also from the economic benefits of tourism.”

To replace eroded sand, boats dredge sand offshore and move it to the coast to nourish beaches. It works – after a seawall rendered Miami Beach virtually nonexistent in the 1970s, nourishment replenished the wide, white-sand beach.

The sand must be replaced every two to eight years as erosion continues. In the SANDAG report, which does not account for the exceptionally stormy 2022-2023 winter season, only the beaches that received sand nourishment were stable or accreting.

The United Nations in September warned that the six billion tons of sand extracted from the sea annually is threatening marine life, contributing to the salinization of aquifers, and disrupting the habitats on both the ocean floor and on beaches receiving sand nourishment.

Additionally, there is some debate about whether dredging for sand exacerbates erosion by further disrupting the natural cycle of ocean sediment redistribution.

But, it’s effective at restoring beaches, and there are seemingly no alternate solutions.

Coronado is one of only three beaches in the SANDAG report that experienced a 2022 decrease in its width. Four others are considered stable, and three are accreting.

“Sand nourishment is the only option we can see going forward,” said Coronado City Council Member Carrie Downey. “And this study did show that it was effective for 22 years, which is not bad.”