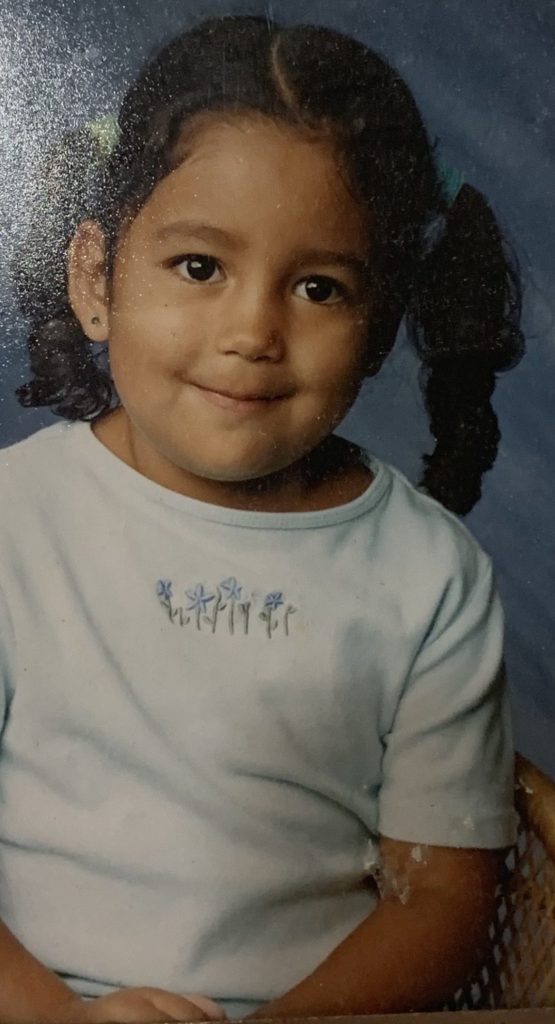

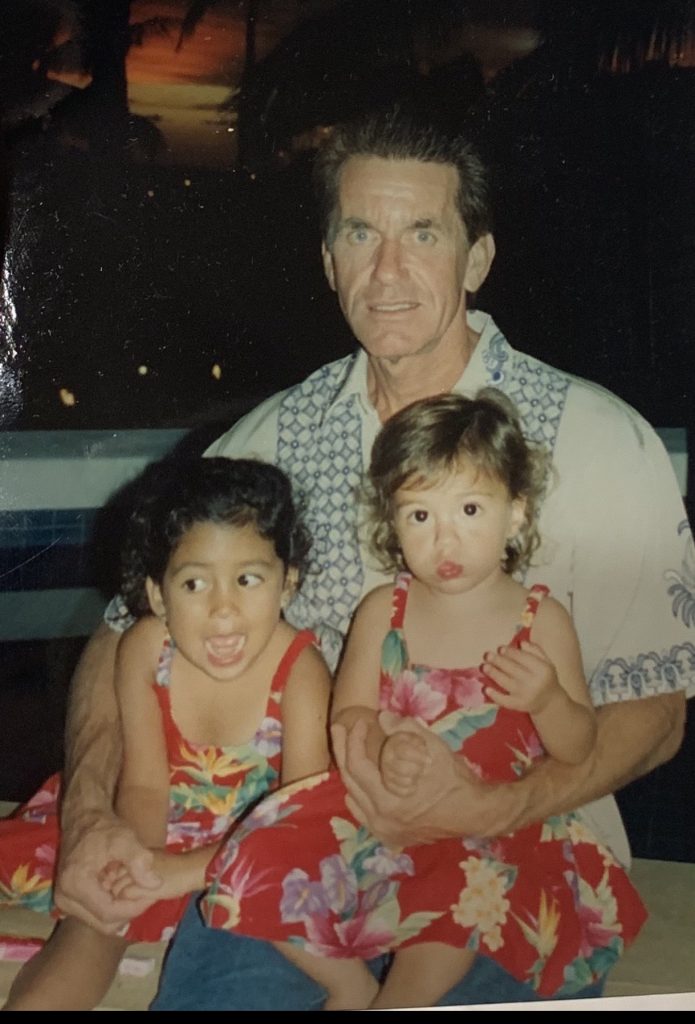

Esme Ronis knew that she was different from the rest of her family. Born in La Paz, Mexico, and adopted by a white family, she grew up in Coronado for her entire life, and attended Coronado schools. Although she enjoyed cozy family get-togethers with her five siblings, and felt loved and supported at home, things got hard when she entered middle school.

“Being a minority in Coronado used to make me feel proud,” she says. “My parents raised me to be proud of my differences, to embrace my dark skin and dark hair. However, once I went to Coronado Middle School, I was made to feel ashamed for the things about me that my parents said made me special.”

Esme recalls some peers asking her why she did not look like her parents. When she told them she was adopted, the conversation turned ugly.

“I explained that my parents chose me, all the things my parents had taught me,” says Esme. “But the girls gave me a disgusted look, and said, ‘Why would we want to hang out with you when your own parents didn’t want you?’”

She said she felt ashamed. It was a new feeling for her.

“Ashamed to look different, and ashamed to be different than everyone around me: teachers, students, faculty included,” said Esme. “The Coronado community at large feels very ‘color-blind,’ but not in a good way. People pretend that race doesn’t matter, which means they ignore when people like me are treated differently because of their race.”

Esme said she was compelled to share her story because she truly believes in the Coronado community, and the goodness of the people who live here.

“I wouldn’t be sharing my experiences if I didn’t think this was a community that would be open, receptive, and supporting,” says Esme. “I believe in the people of Coronado, and truly feel like we can make this community more accepting and inclusive.”

Esme says she would love to see Coronado and Coronado schools set the example for other communities as a leader when it comes to inclusivity.

“People want to pretend that racism doesn’t happen in Coronado, but it does,” says Esme. “I am here to tell you my story because it did affect me and affected my education and my ability to go to school every day.”

Esme says that in addition to racist comments from peers, she experienced self esteem-crushing encounters with a school faculty member which left a lasting impression.

She recalls when this faculty member made all of the girls in her grade play a game called “Over the Line.”

“If they said something that applied to you, you had to cross over the line,” said Esme. “I remember [the adult] said to cross the line if you were Mexican, and only three girls crossed the line. Then [the adult] looked directly at me and said ‘cross the line if you are adopted.’”

Esme remembers crossing the line alone.

“I have never felt so ashamed of who I was,” says Esme. Later in school, Esme says this same faculty member accused her of stealing, and even told her that she needed therapy because she was “different.”

“[The adult] made me feel like I was nothing; made me feel worthless,” shares Esme.

Esme recalls other racist comments at school. She remembers hearing the “N” word used, along with a student who would hang the Confederate flag off the back of his truck. Esme said teachers laughed it off.

“Experiences like these are why I felt unwelcomed in Coronado,” says Esme. “I began dying my hair blonde, and wearing lighter makeup in hopes of fitting into the mostly white population of my high school.”

But the racism continued.

She endured verbal assaults like, “are your real parents drug dealers?” and “So you belong in an orphanage?” and “You are a fake Mexican.”

After graduation, moving to New York City proved to be a breath of fresh air.

“Getting out of Coronado, and moving to New York City, I was finally able to meet people who accepted me and liked the different, unique things about me,” says Esme. “Nobody made fun of me, and nobody bullied me with racist comments like they did in Coronado schools. For a while in Coronado, I couldn’t tell someone I was adopted without crying.”

Esme says she has felt like she was racially profiled by law enforcement officers in Coronado on at least one occasion. Once, was pulled over after curfew with a friend who was black. Both Esme and her friend were asked to get out of the car. She said it was scary, and she felt very intimidated. The officer let them go when Esme explained that they went to Coronado High and she lived only a block away.

Another time, she was pulled over with a boyfriend who was white. This time, things went differently.

“This officer did nothing to make us feel intimidated…he was almost nice,” says Esme. “I couldn’t help but think if I had been with my black friend again, things would have been extremely different.”

Esme says she is disgusted by George Floyd’s death, but not surprised.

“I have always known that systemic racism permeates our criminal justice system, especially our police force,” says Esme. “This instance was not surprising to me, as I have always been acquainted with the reality that is police brutality. I know this by virtue of being a minority and by growing up with criminal defense attorneys as parents.”

Despite the horror of Floyd’s murder, Esme says she is grateful to see the consequent flood of information and expositions of the horror of police brutality.

“I’m learning more every day, and I am glad to see that people are finally opening up their ears to listen to the experiences of the black community,” says Esme.

What does Esme want white people in Coronado to know about racism?

“I know that many people in Coronado might consider themselves colorblind, or think that because they don’t hate other races, they are not racist,” says Esme. “That is not the case. Racism exists right here in the Coronado community. White people first need to recognize this. Secondly, they need to understand that racism isn’t a minority issue they need to empathize with. It’s caused and upheld by white people, whether or not they believe themselves to be racist. That is why it’s not enough to be ‘not racist,’ you must be anti-racist.”

Furthermore, there are several things people can do to be better allies to non-white friends.

“First of all, white people can start by listening to people of color and what they are going through,” says Esme. “When someone exposes racism within your community or within your own actions, don’t get defensive and don’t invalidate those who came forward. Our experiences are real, they are hurtful, and they are valid. Listen with open minds and open hearts.”

Esme says she can’t count how many times she has come forward with racist encounters that she has experienced, and the authority figures who were supposed to help her, instead belittled her.

“They say, ‘it wasn’t a big deal,’ or ‘it wasn’t meant like that,’” says Esme. “By reaching out to people of color to listen to their experiences, it shows that you are open to learn. We appreciate the chance to be heard.”

Esme says it’s OK to have made mistakes in the past. No one is perfect.

“What matters is how you move forward, acknowledge your history and past ignorance, and take action to make your community a more accepting place for those who look like me,” says Esme. “Even as a person of color, I have made ignorant statements without grasping or truly understanding how what I said, or did, was hurtful. I improve by listening to black voices and doing better by them.”

Esme says she has big hopes for ending racism in our country. She says we need to openly condemn the systemic racism within our institutions.

“By acknowledging that it exists and educating ourselves on the way racism presents itself, we can spot it in our politicians and politics,” says Esme. “I would like to see the many openly racist politicians we have in office voted out, and I would like to see anti-black and anti-POC policies voted against. I would like to see representation in my elected officials, meaning more people in Congress and political offices that look like me.”

These days, Esme is back in Coronado, studying fashion business at Mesa College after two years of fashion design school in New York City. She hopes to get her associates degree and go back to NYC to study more fashion. Ultimately, she would like to be a fashion buyer at a high-end fashion brand.

Although she loves New York, a piece of her heart will always remain in Coronado. She says she looks back on her graduation from Coronado High as one of the best moments of her life.

“It really was one of the best days of my life so far,” says Esme. “I got to do something I never thought was possible, and attend college.”

When she’s not studying, she’s jet skiing on the San Diego Bay with her family. Before the COVID quarantine, she loved dining at Tartine’s and The Henry. Now, she spends lots of time with her boyfriend, relaxing and watching movies.

“I don’t want people to think, reading this article, that I hate Coronado,” says Esme. “Because I don’t. It’s where I grew up, it’s where my family is. But I believe we can be the example of how communities can be better and more inclusive. I believe sharing students’ stories is a good place to start.”

Esme shares that her little cousin has started 6th grade at CMS. Like her, she is Mexican, with dark, curly hair and darker skin. Every day, Esme worries she will face the same injustices she suffered.

“That’s why I am doing this interview; I want to make sure that my cousin and many other kids younger than me do not feel how I felt going to Coronado schools,” said Esme. “I want things to change now.”

Esme says sharing her experiences is helping her close a hard chapter in her life. Coronado has given her a lot, but it’s also taken a lot from her as well. Most importantly, Esme doesn’t want racist experiences to damage any young person’s self esteem.

“By sharing my thoughts and what happened to me, hopefully I can tell one other person of color in Coronado schools that it is not acceptable to be treated differently because of the color of their skin. If I can do that, then sharing this very personal time in my life is worth it.”