The announcement of the selection of vendors to build the Trump administration’s border wall prototypes in the San Diego border sector was made a couple weeks ago. Once instructed to go ahead, those vendors have thirty days to build their prototypes and they will be evaluated for up to 60 days thereafter. Homeland Security has described the requirements for the wall as being made of either concrete or see-through material, between 18-30 feet high, and sunk at least 6 feet into the ground (so as to prevent tunneling). The goal of the wall would be to decrease illegal immigration and smuggling.

The San Diego sector of the border patrol currently has about sixty linear land miles of border with Mexico. All but 14 of those miles currently have barriers of various sorts. It made me wonder, what is the new wall meant to do that the current barriers don’t? To get a sense of this, I took a trip down to visit one spot on the border – International Friendship Park.

Friendship Park straddles the border just about 12 miles south of Coronado. According to the Friends of Friendship Park, this location has existed as a meeting place since the first meeting of the US-Mexico Boundary Commission at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1849. Today, it is neither freely accessible nor all that friendly, as I found when I visited last weekend.

Friendship Park straddles the border just about 12 miles south of Coronado. According to the Friends of Friendship Park, this location has existed as a meeting place since the first meeting of the US-Mexico Boundary Commission at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1849. Today, it is neither freely accessible nor all that friendly, as I found when I visited last weekend.

I drove out of sunny, prosperous, lovely Coronado, somewhat crowded along Orange Avenue on such a nice weekend day. It only took about 20 minutes to get to the turnoff from I-5 along Dairy Mart Road. And, while the change in atmosphere did not come suddenly, it was stark. The road went from paved to rock to, in some places, dirt. I drove across parts of the Tijuana River Estuary Open Space Preserve through scrub and other plant life that became increasingly fertile the lower I went. It was not hard to imagine that when rain came, much of the road might be closed or impassable. Eventually, the road rose up to a peak and a cement parking lot and park overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Look north, and you would see gorgeous beach with crashing waves; look south, and you would see a tall, dark wall extending out into the ocean to the west and turning into a metal fence structure for as far as you could see in the other direction.

I drove out of sunny, prosperous, lovely Coronado, somewhat crowded along Orange Avenue on such a nice weekend day. It only took about 20 minutes to get to the turnoff from I-5 along Dairy Mart Road. And, while the change in atmosphere did not come suddenly, it was stark. The road went from paved to rock to, in some places, dirt. I drove across parts of the Tijuana River Estuary Open Space Preserve through scrub and other plant life that became increasingly fertile the lower I went. It was not hard to imagine that when rain came, much of the road might be closed or impassable. Eventually, the road rose up to a peak and a cement parking lot and park overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Look north, and you would see gorgeous beach with crashing waves; look south, and you would see a tall, dark wall extending out into the ocean to the west and turning into a metal fence structure for as far as you could see in the other direction.

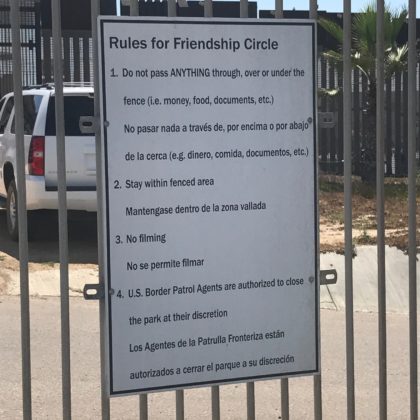

Visitors who want to meet up with friends or family on the other side, park their cars and walk through a gate into an area that is open between 10 am – 2 pm on weekends only and where only 25 people are allowed at a time. When I went through, the border agent was monitoring the area from inside his truck. He came out from time to time to talk with people and to tell us we were not allowed to go down to the beach here – we had to stay on the paved section between the fence behind us and the border in front.

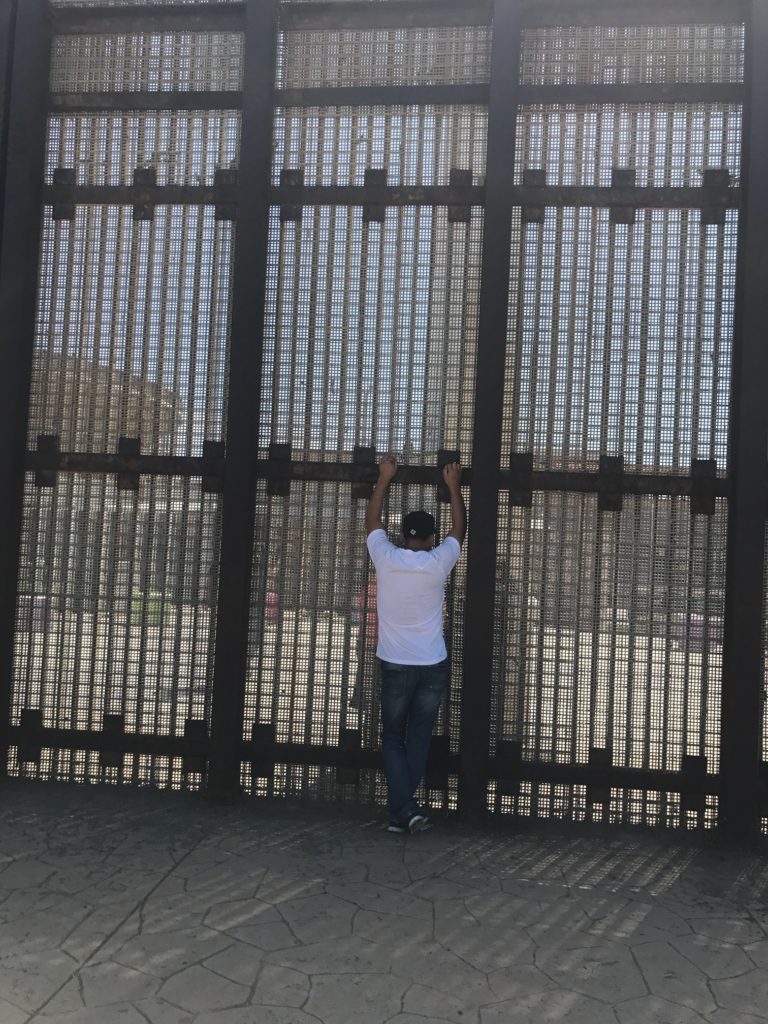

The border fence itself varies from a wall going down to the ocean to a thick metal fence with tiny holes through which people might touch fingertips (but not more). It becomes a more open iron fence with bars that have wide spaces where you can see people’s faces clearly and could touch one another, except for the strip of grass which is roped off, keeping people separated and almost out of hearing distance of one another, if trying to converse. It is hard to know if Friendship Park is meant to be a humanitarian gesture since it does allow separated families to meet, or a hideous reminder of that same separation.

The border fence itself varies from a wall going down to the ocean to a thick metal fence with tiny holes through which people might touch fingertips (but not more). It becomes a more open iron fence with bars that have wide spaces where you can see people’s faces clearly and could touch one another, except for the strip of grass which is roped off, keeping people separated and almost out of hearing distance of one another, if trying to converse. It is hard to know if Friendship Park is meant to be a humanitarian gesture since it does allow separated families to meet, or a hideous reminder of that same separation.

The Border Patrol agent told me that this was his regular duty, to monitor the park on weekends. He said that some people come regularly, not every week, but some come once a month. He took pains to point out that the barrier is not a wall, but a fence. He said that while the barrier had started out as a relatively small fence, it was increasingly strengthened over the years as the as the drug war and smuggling became focused on Tijuana. From his point of view, the wall wasn’t so much meant to keep families separated as much as it was to keep crime out.

The Border Patrol agent told me that this was his regular duty, to monitor the park on weekends. He said that some people come regularly, not every week, but some come once a month. He took pains to point out that the barrier is not a wall, but a fence. He said that while the barrier had started out as a relatively small fence, it was increasingly strengthened over the years as the as the drug war and smuggling became focused on Tijuana. From his point of view, the wall wasn’t so much meant to keep families separated as much as it was to keep crime out.

According to the California Border Patrol website, “illegal alien” traffic steadily increased throughout the 1970s in the sector, peaking in 1986 at just over 600,000. In the 1990s, following a series of measures to enhance border security, apprehensions dropped dramatically. And, in 2011, there were just under 43,000. So, maybe the border patrol agent was right. Maybe the current barrier was a successful deterrent to crime. But, then, why the need for a new wall? And, at what cost?

There are many critics of Trump’s wall, ranging from members of his own party who don’t want to foot the bill (estimated by Homeland Security to be expected to run to more than $20 billion), to environmentalists who don’t want to destroy natural habitats and migration routes, to individual landowners, particularly in Texas where some 95% of the land needed for the barrier wall is estimated to be in private hands. But, perhaps the most powerful critics with respect to the San Diego region are those who argue against it on primarily humanitarian grounds. If crime has already declined so dramatically over the years, then maybe the Gregory Z. Smith, Mayor pro-tem of Las Cruces, New Mexico, got it right when he wrote in July of this year: “No matter what leadership in Washington, DC may offer to justify this massive expenditure and no matter who actually pays for it, this wall says to our neighbor, ‘We fear you, and we have no respect for you.’”

Certainly, for the Friends of Friendship Park, the activity around building a new wall does not bode well for their goal of “creat[ing] a future where the public will have unrestricted access to this historic meeting place.”

But, for us, who are neighbors, it makes sense to know what is there now so we can better understand the implications of a new wall.