LOCAL ENTREPRENEUR AND SURF LEGEND DIES

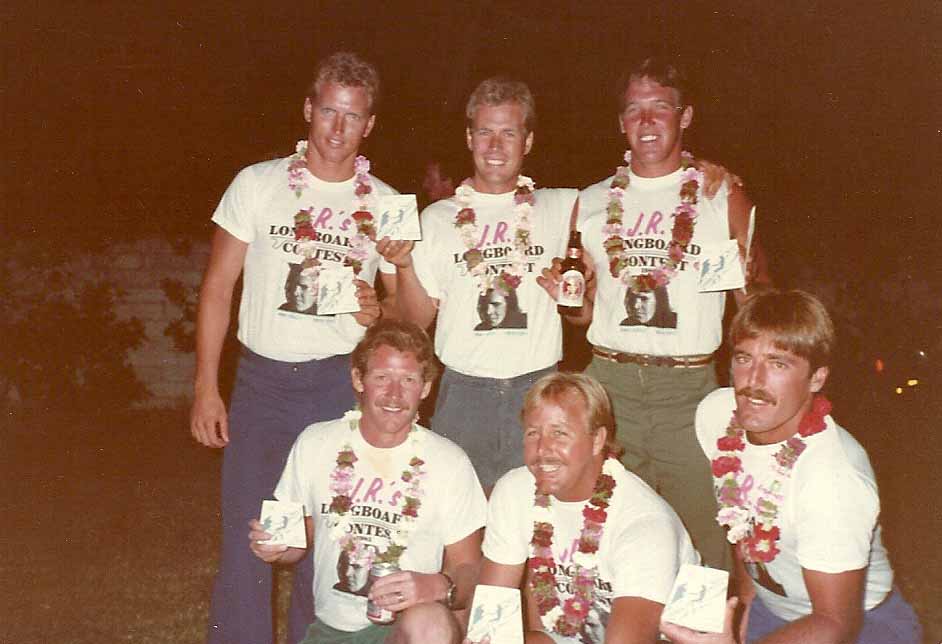

Over his lifetime, Pete Johnson had created thousands of surfboards and rode tens of thousands of waves, all over the world. He managed the Rusty Surfboard company for ten years and specialized in the food industry, opening or managing ten Chart House restaurants.

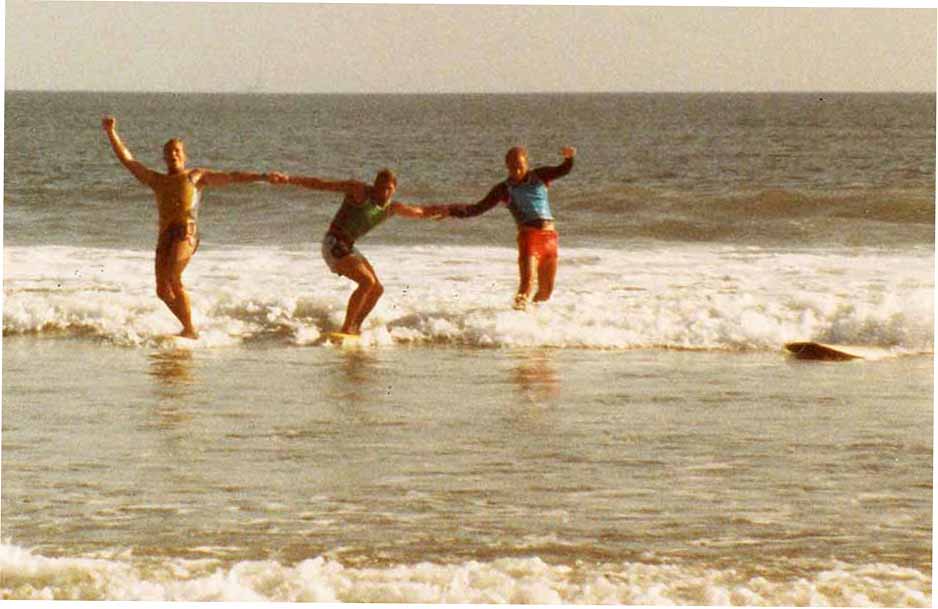

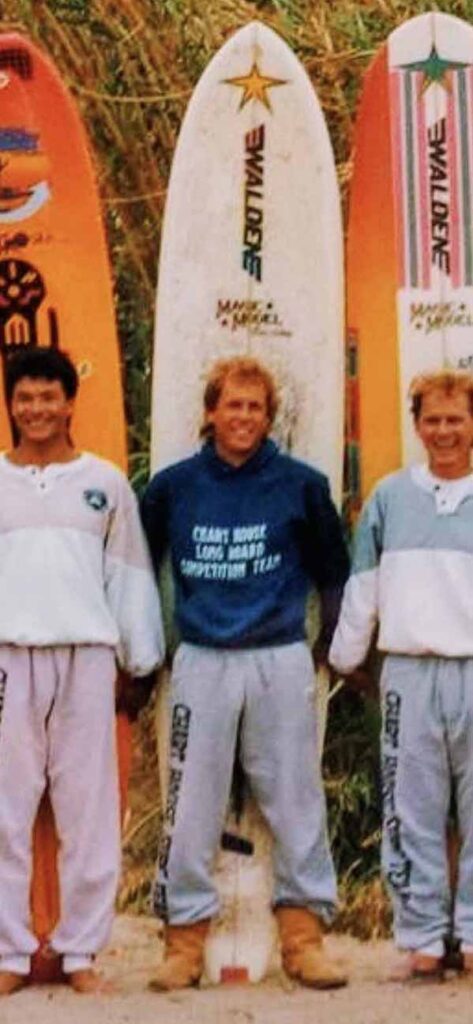

He surfed for 50 years, eight of those as a professional surfer. He had three major tournament wins and surfed on the Chart House Professional Longboard Team.

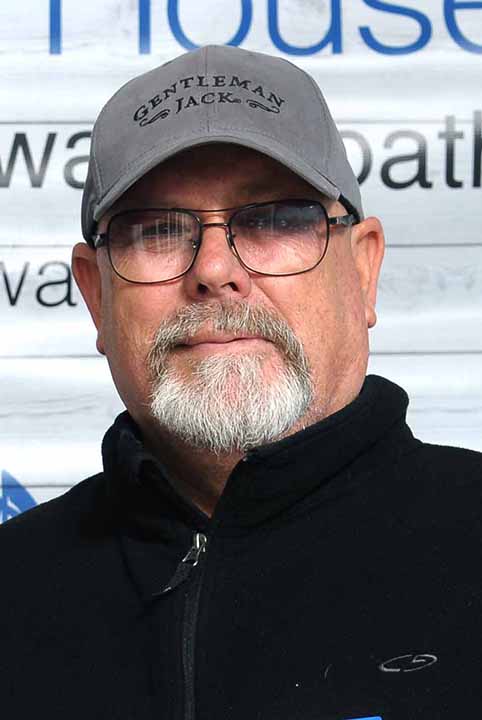

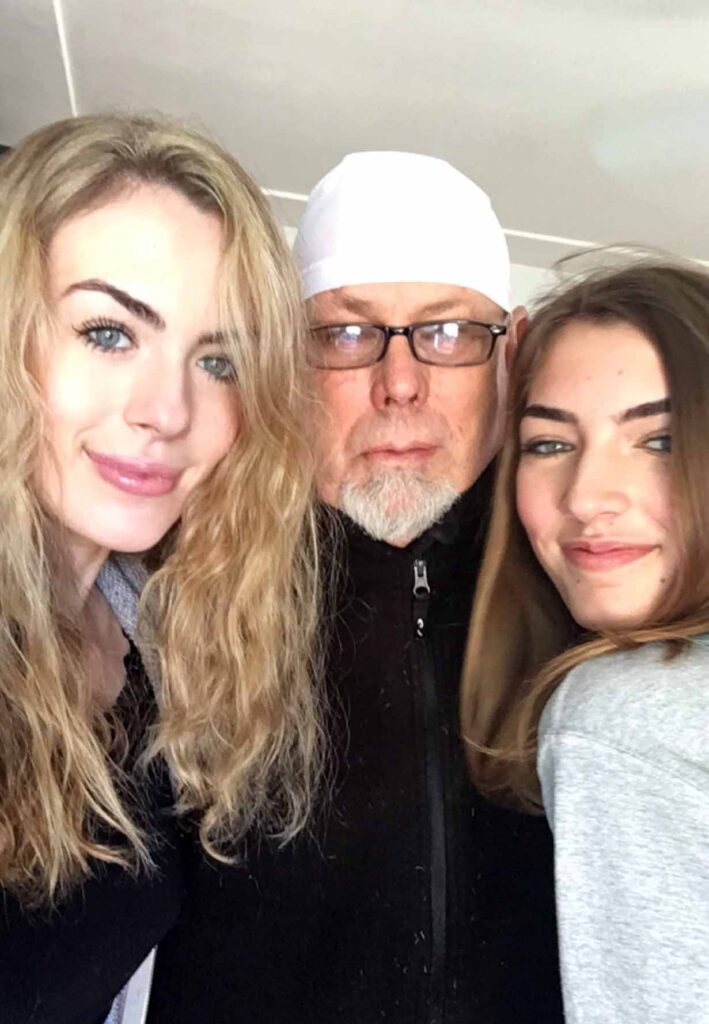

And yet, Pete’s proudest moments were rising to the challenge of caring for his two young daughters in the wake of their mother’s sudden death. Pete died June 20 from an aggressive brain tumor, in his Coronado home, with his daughters and sister Margaret by his side. He was 66 years old.

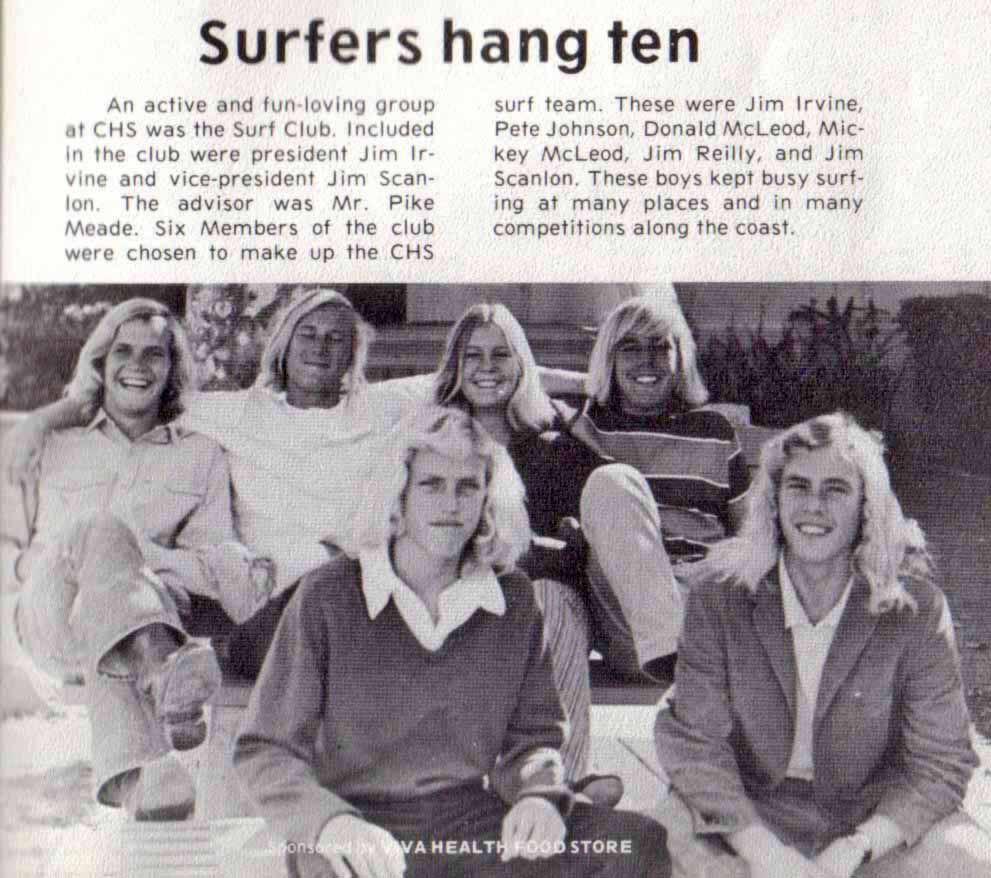

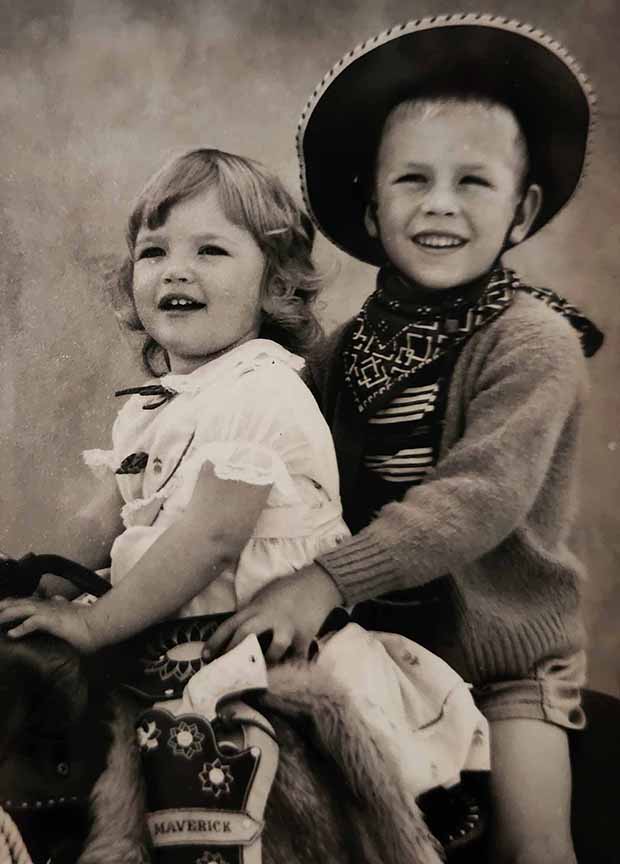

Peter Christopher Johnson was born April 12, 1956 as one of 13 children known on Coronado Island as, “The Johnson-Sweeney Clan.” He was a 1974 graduate of Coronado High School.

Growing up in Coronado in the 1960s and ‘70s, everyone knew “The Johnsons and Sweeneys.” They were one family, after a fashion, and resided in a large home at 575 ‘A’ Avenue.

Pete’s parents were Johnny Johnson and Margaret Anne Johnson. She died in 1959 in childbirth. He remarried in 1961, to Beebe Sweeney. When they married, his father had seven children from the prior marriage and Pete’s new stepmother had five of her own. Together they had another child, Tiger Johnson. “They wanted to have one last child, together,” said Pete, “to help bond our two very large and very different families. It worked. We all loved Tiger.”

His father, “Johnny” Johnson, was a WWII fighter pilot and highly decorated hero in the Pacific Theatre. He was put on an island with nothing more than a knife, a radio and orders to “spy on the Japanese.” He survived for eight months, living on what food he could steal from the enemy. At war’s end, he had received the Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Meritorious Service Medal, Air Medal, Navy Commendation Medal and more than 50 others.

If nothing else, that experience helped prepare him to raise 13 children in Coronado during the rebellious ‘60s, and his children loved and admired him dearly.

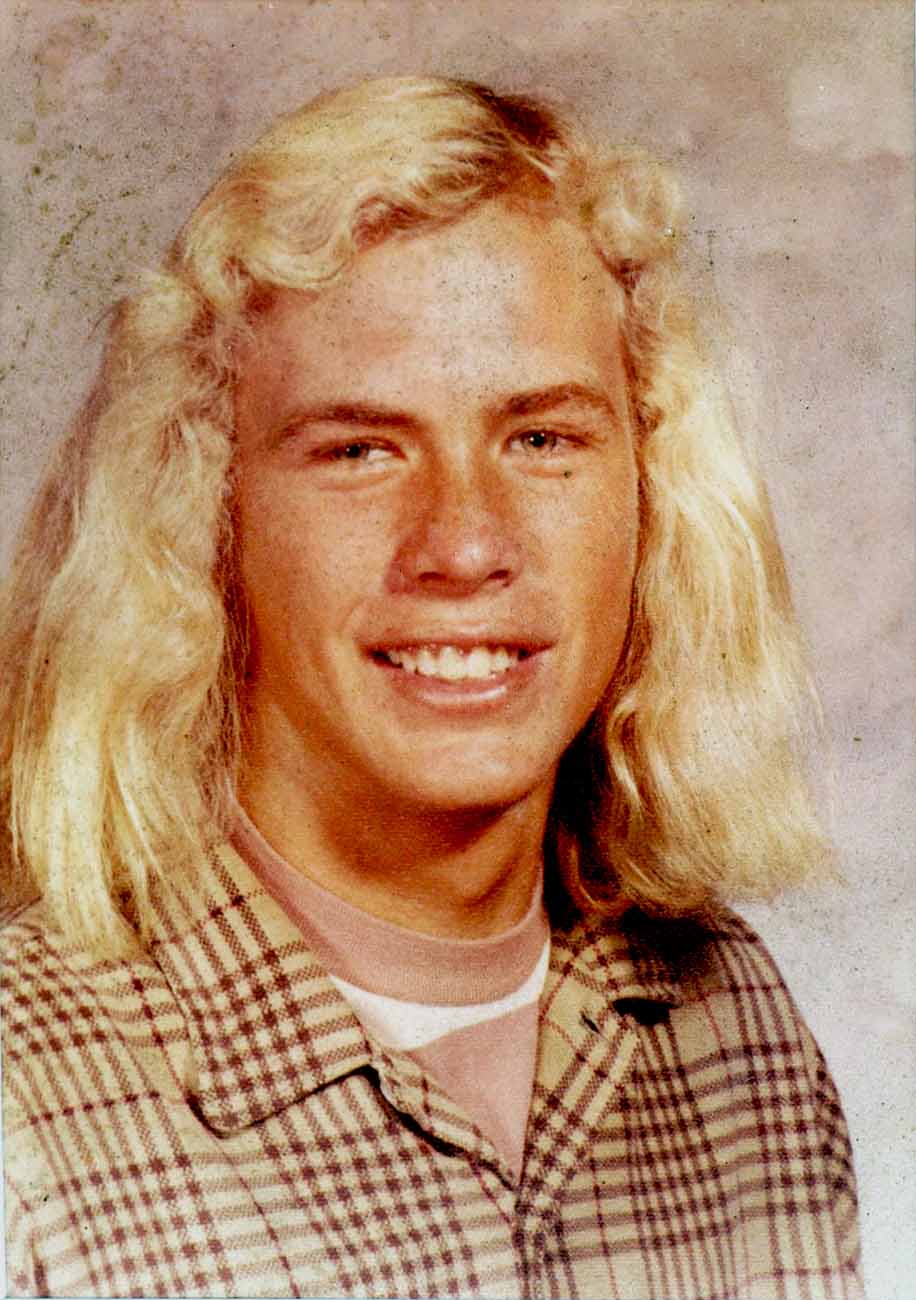

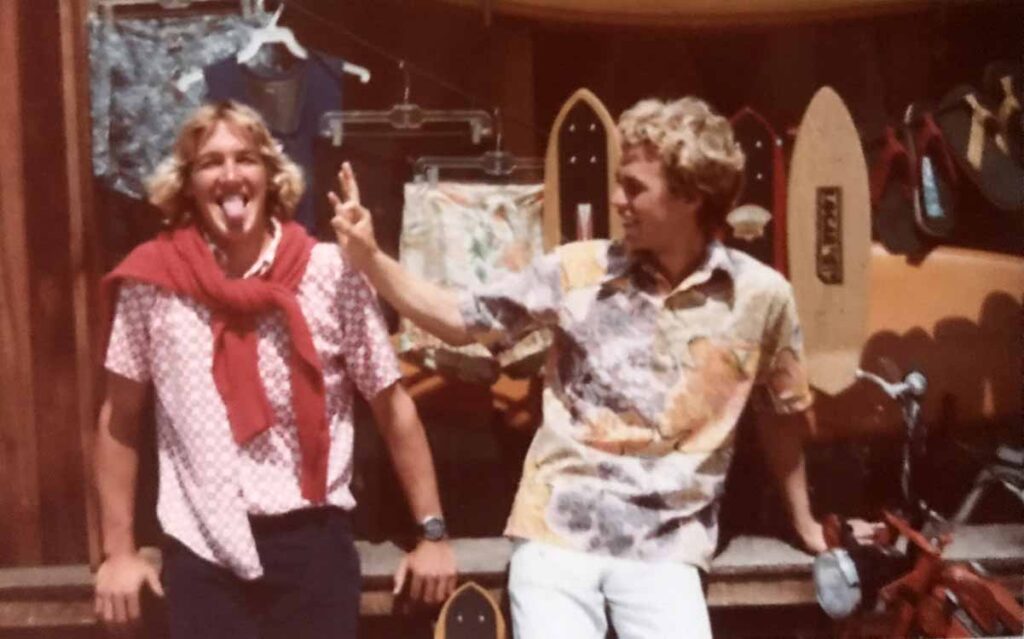

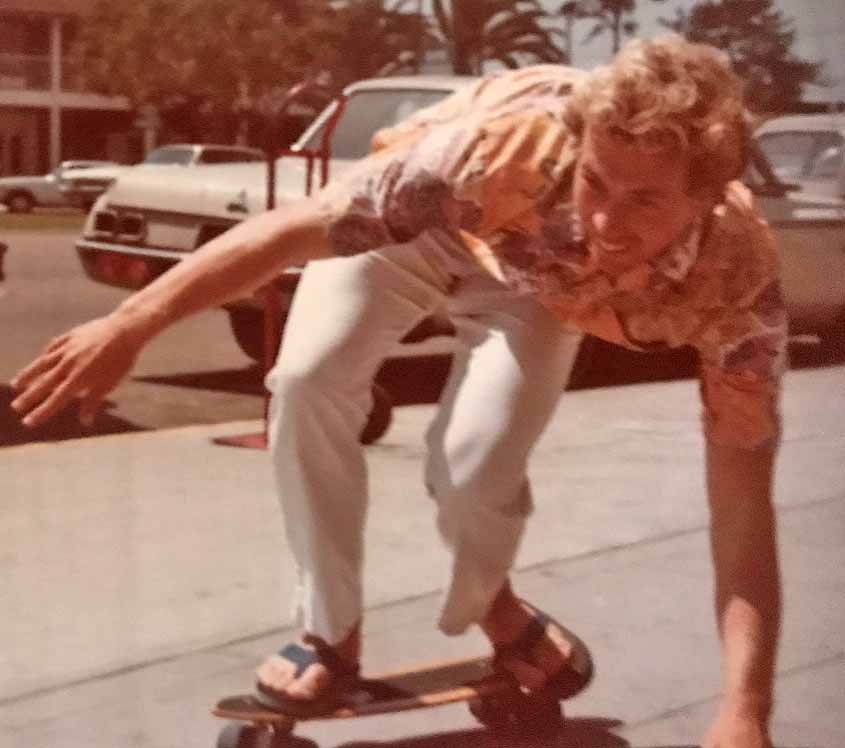

These Coronado High School yearbook photos capture a young Petey Johnson. The year before, CHS abolished men’s hair regulations, and suddenly every young man in the school had long hair. It was definitely a sign of the times:

In Coronado, Pete was part of a generational pack of young surfers nicknamed affectionately, “The Rats,” by the generation just ahead of them, who were known as, “The Cats.”

Together they were fearless in their surfing styles, dominating the large south swells of summer that pounded annually on both sides of the fence at North Beach, a break known as “Outlet.” These southern August swells, and the adventures of the Rats and the Cats are well-known in Coronado lore.

The surf was always just that much better on the military side of the fence. Pete and his friends were perpetually defying the rules, the laws, and sneaking around, over or through that fence.

Military and civilian police tried, but failed to stop the boys from surfing those waters. In the end, policing efforts only fueled their desire to catch the “off-limits” waves. Like the forbidden fruit, they couldn’t resist the danger involved in seeking out the perfect wave.

The battles for a little stretch of beach called “Outlet” remain a favorite memory of Coronado surfers from that era. The photos of surfer and professional photographer, Steve Ogles, captured much of this era, as you can see in this story.

When the shortboard revolution came in 1967, everyone began to cut their longboards in half. Pete and his pals began to strip back the glass and reshape the longer boards, giving them pintails and a fin box. They were the rage, as suddenly “shorter” was better in the massive waves of Outlet, and the burgeoning surfboard industry. These shortboards fit nicely in the tight and unforgiving barrels at Outlet.

Pete worked at Coronado’s first surf shop, Du-Ray’s, on Orange Avenue. Owner Bob Duryea taught him to repair dings on surfboards and then sand blanks. “I think I sanded every board that went through that shop in 1973-74,” Pete said.

Before long, Pete was surfing with, and working in surfboard shops alongside surfboard making giants, Richard Jolie and Denny Bessell. Most of the surfboards Pete either sanded, or reshaped down from 10 feet to six feet. That was what the era demanded, and Pete had a distinct head start on that process.

He landed a job washing dishes at the old Chowder House (now Chez Loma Restaurant). When the restaurant changed hands (and names), Pete was kept on as their first busboy. He saved money like crazy and headed to Hawaii. For young Coronado boys at that time, Hawaii was Mecca for surfing. It was the destination to beat all destinations.

While there, Pete began to surf with a local surf legend and shaper named Billy Hamilton. Before long, Billy had hired Pete to work in his surf shop, and moonlight at night babysitting his children (one of those children, Laird Hamilton, is now arguably the most famous surfer on the planet).

At this time, Pete had long blonde hair. Hamilton’s wife pulled him aside and informed him that the Hawaiian locals would be rough on him with that hair, so he cut it short. Then, while working at the Rice Mill on Kauai, the cooks, all local Hawaiian boys, took a liking to him, and he was invited to surf with them at breaks no “haole” boy would otherwise have been allowed to surf. Pete was a very good surfer by now, but suddenly his ability in large waves soared.

Whenever possible, Pete pulled double shifts at island restaurants, either washing dishes or bussing tables. Somehow, he kept money enough coming in to extend his island experience.

While in Kauai, Pete ran into two other Coronado High School pals, Frank Nicholls and Clancy Greff. They had a very successful business catering to tourists – Captain Zodiac Raft Expeditions – that explored the island coastlines of Kauai and Maui.

Frank left for Mermaid Beach, Australia to start a suntan lotion business. Pete soon followed. “I’ll never forget the sight of Frank walking along Australia’s beaches, selling suntan lotion,” said Pete. “He had a tank of lotion strapped to his back, with a spray nozzle.

“As Frank walked the beaches, naked women would stand and pay him a quarter to spray their bodies with suntan lotion. Hahaha. I had never seen such a thing.”

Frank put Pete to work, and before long, he was making money again, and exploring the many surf spots Australia had to offer. “I’ll never forget Pete,” said Frank Nicholls in a phone call from Australia. “He was a great friend and a great surfer.”

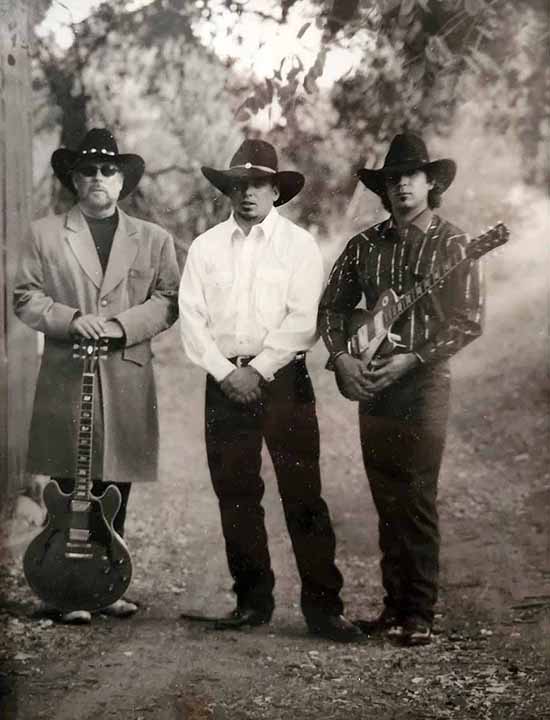

Meanwhile, Pete continued to hone his skills on the guitar. He loved to play and write songs. Music had always been a part of his life. In the early 1960s, while in the 7th and 8th grade, he performed duets (guitars and vocals) with childhood friend Jeannie York.

Later he performed in the Johnny Cook Band with Joey Harris, and played jazz with the Hanalei Band as songwriter, producer and arranger.

He continued to play with numerous bands in the islands and on the mainland. In his own band, Southern Tide, he co-wrote a song, “Slow Burning Flame,” which became number one on the Billboard Chart, under “New Country.” It made him a lot of money, he recalled.

“I never wanted a straight job,” Pete said. “I never wanted to be in an office all day long. That’s the way surfers are. So everywhere I went I worked by instinct and experience, and made my way surfing, playing my music, and working restaurants to keep meals on the table and the rent paid.”

Pete’s father called in a promise Pete had made him years before to go to college. He sent Pete an airplane ticket, and the entrepreneurial young surfer left Australia and enrolled at San Diego’s Mesa College, even though, in the long run, Pete’s education proved to be the world.

While going to college, Pete met his first wife Dodi. He took a job at the La Jolla Chart House to bring in spending money (1978). With his people skills and restaurant experience, Pete worked his way up to head waiter in no time.

Then the Chart House offered him a management position. “I had worked my way from dishwasher to manager,” said Pete. “Then I became general manager at the Oceanside Chart House (1986-87). I had a great time.”

All in all, Pete estimates he worked at ten Chart Houses, opening a handful in exotic places in both the Islands and on the Mainland.

One night he was at the hostess stand at the La Jolla Chart House and a regular customer, Rusty Preisendorfer, asked him if he was interested in coming to work for him. Rusty was fast becoming a hot commodity in the surfing industry for his surfboards and clothing lines.

“Of course, I said yes,” Pete recalled years later. “We had breakfast the next morning and he made me an offer. We came to an agreement quickly, that I’d be general manager of his surfboard factory and two of his surf shops.

“At the time it was a big, unorganized mess. I was able to use all my Chart House management experience and my people skills to turn everything around. I made sure customer service was a priority. I’m very proud of the work I did there.”

Pete was at Rusty for ten years. He often said it was the perfect combination of running a business, building surfboards and designing to his heart’s content.

Pete designed a line of wakeboards that sold out faster than they could produce them. He took concepts of cutting-edge surfboard design and applied things like v-tail and concave into wakeboard design. He suddenly found himself studying fluid dynamics.

Today, when looking at the Rusty website, many of the ideas and concepts Pete introduced are still a priority – swallowtail shortboards, wakeboards, customer service.

In 2001, Pete started his own surfboard company, Kane Garden (KG Surfboards). Then, in 2006, he sold the rights to KG and started Delray Surfboard Designs. He named the company after his daughters.

Pete had enormous success with the two companies, making and selling thousands of custom-made surfboards and stand up paddle boards. He is known for his Orca Board, a speed egg, as well as his splash resin works and bright color designs.

His daughters continue Pete’s legacy by maintaining Delray Surfboards, following in the family surfing tradition, which pleased their father enormously in his final days.

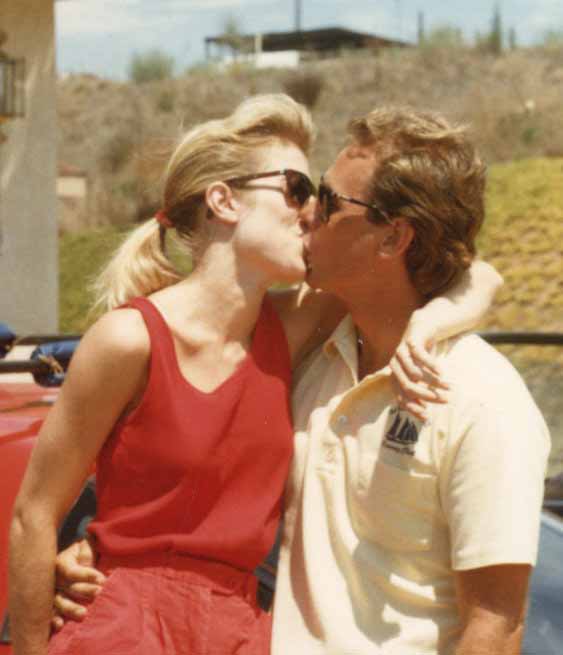

Pete met his second wife Cindy Sauers, in 1985. He described it as, “love at first sight.” They were married in 1988 and their first daughter, Delaney, was born in 1999. Daughter Audrey was born in 2002, and named after the actress, Audrey Hepburn.

Cindy was the picture of health and was studying to be a nutritionist when she was diagnosed with cancer. She died in 2009. The girls were ten and seven at the time.

“It was a chaotic time,” remembered Pete. “The girls wouldn’t allow me out of their sight.”

When this interview was done, Pete was partially paralyzed, bed-ridden, and his now-grown daughters were caring for him in their home.

“You can imagine how my current situation is difficult for them,” he said. “I just don’t have a lot more time. But I tell them every day how much I love them, and how their mother and I will be looking down on them, together, one day soon.”

Peter Christopher Johnson is survived by his daughters Delaney and Audrey (Coronado); siblings Georgia (Bellingham, WA), Bruce (Coronado), Patricia (Bellingham), Elizabeth (Callaway, MD), Virginia (Orange County) and Margaret (Port Orchard, WA). He is also survived by John Sweeney (Reno, NV) and Emma Sweeney (Millbrook, NY).

A paddle out will be scheduled and posted in the local media. Pete has requested donations in his name be made to the Dean Randazzo Cancer Foundation (https://www.thedrcf.org/).

“I want to thank all my friends and family who walked beside me down this path,” he said. “Hopefully we’ll see each other again, with God’s will. Until then, please support my daughters, as they work to keep our legacy alive at Delray Surf Designs. I love you all so very, very much.”