“Around the World in 36 Years: with Baines Haines”

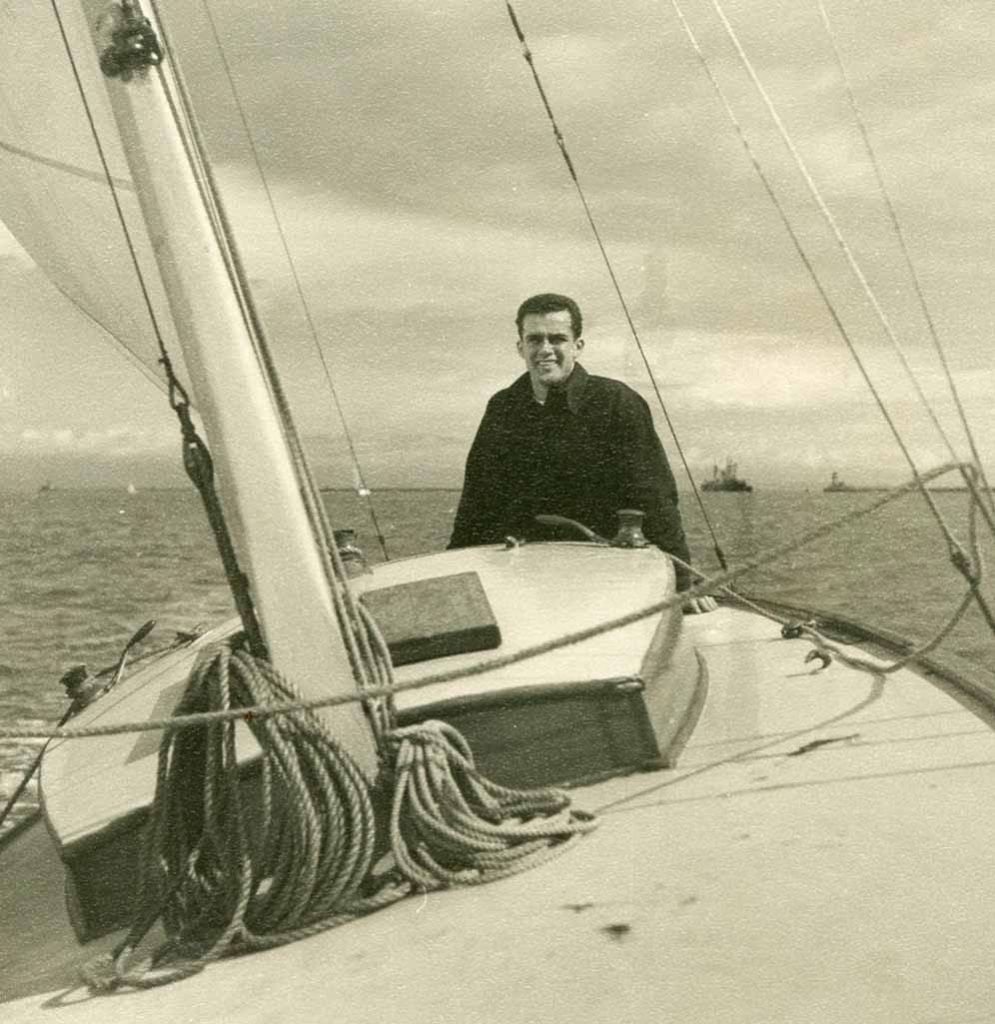

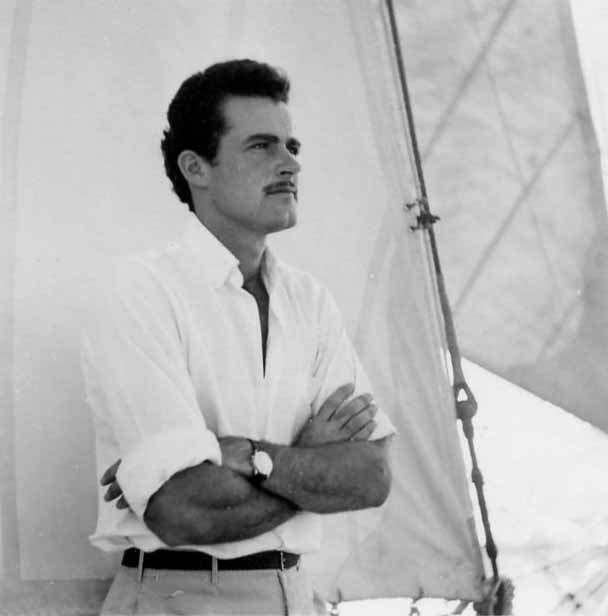

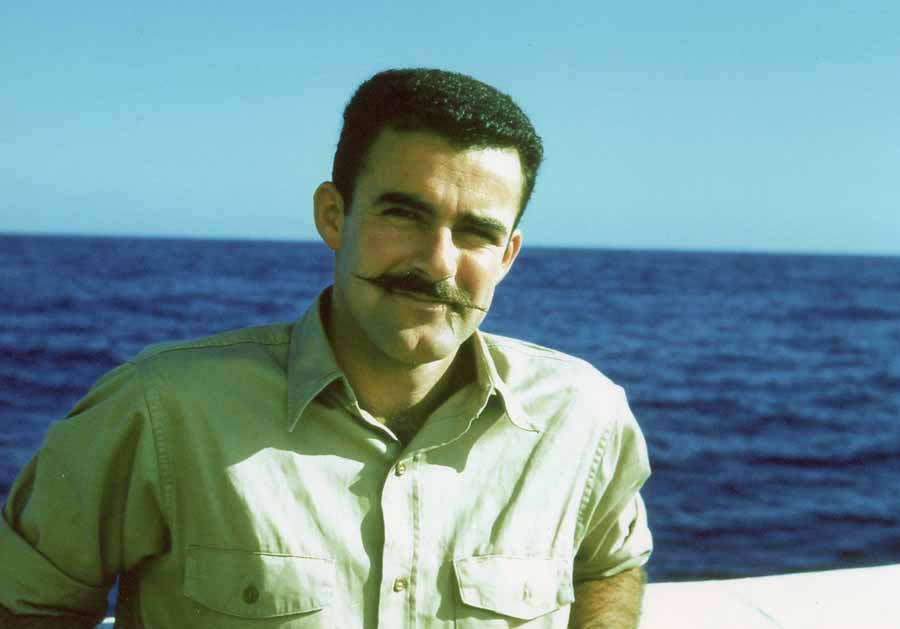

He has survived earthquakes, underwater volcanoes, and sailed through the eye of hurricanes at sea. He was a front-row witness to the closing of World War II; he surfed redwood planks in the Territory of Hawaii. “Baines,” as his friends and family knew him, spent most of his life at sea.

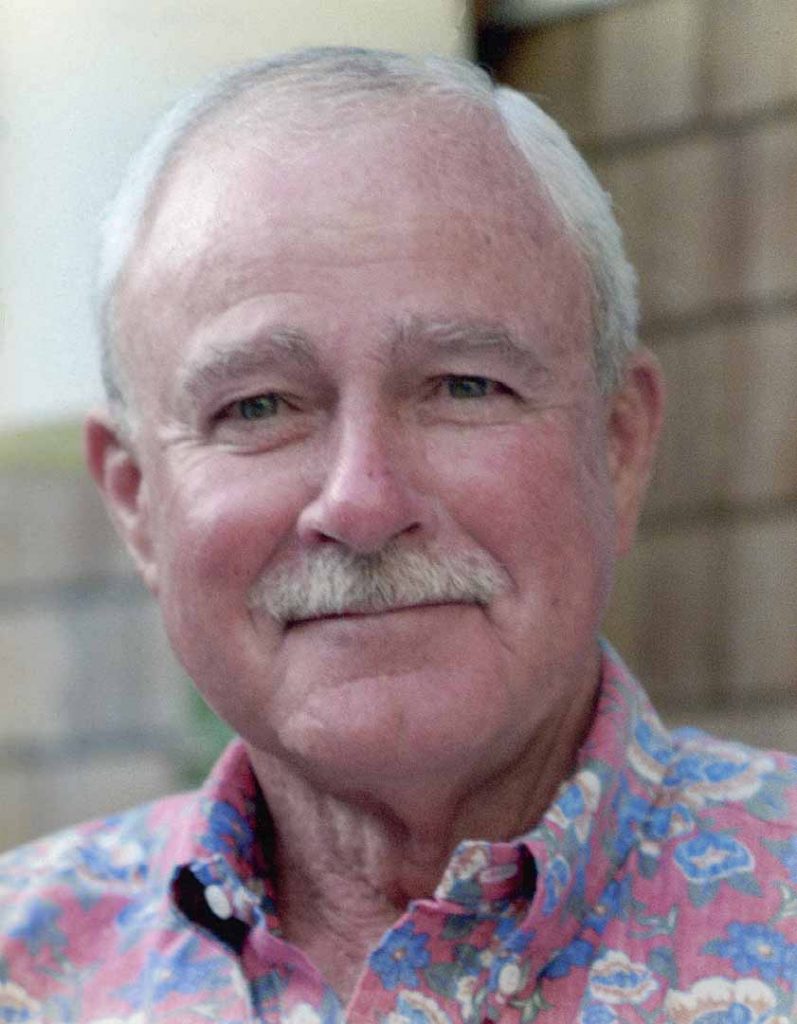

Captain Robert Haines passed away peacefully, January 26, at the age of 92, of complications from pneumonia and pulmonary fibrosis. He was surrounded by his loving family.

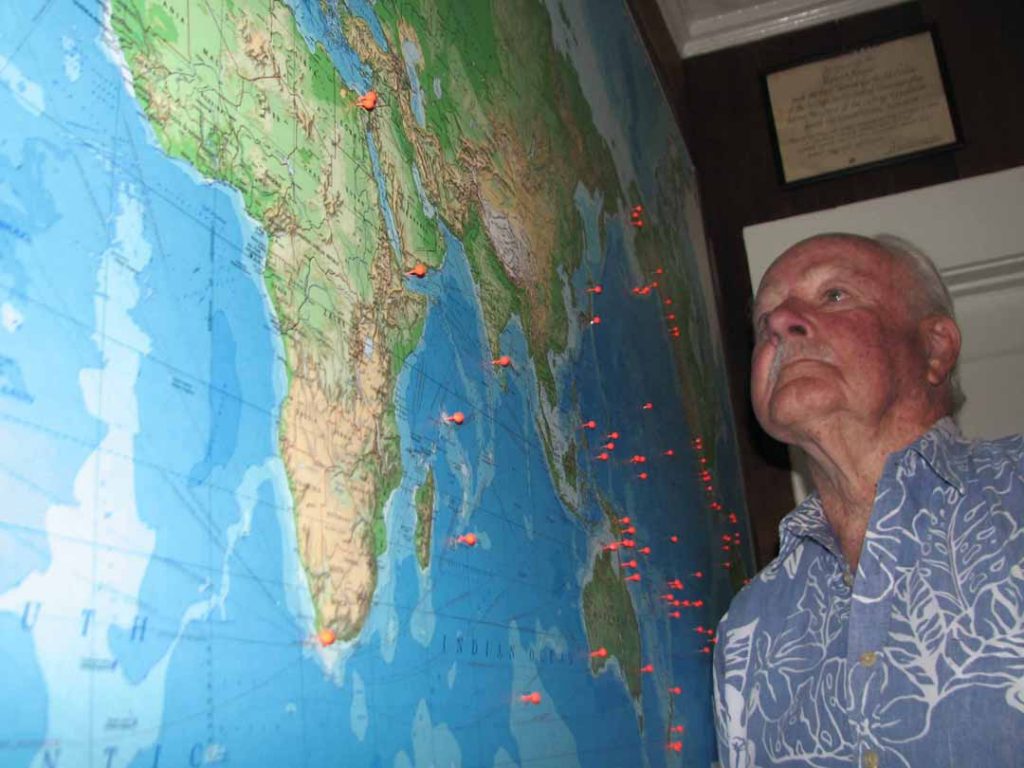

Like a Daniel Boone of the earth’s oceans, Baines helped chart the undiscovered country – the undersea regions of the world. For more than three decades he worked everything from deckhand to scientist-assistant to skipper on the great ships of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography fleet. And he did so in every weather condition known to man.

He is descended from a South African President; brother to a Poet Laureate; and sired an Olympic Gold Medalist son.

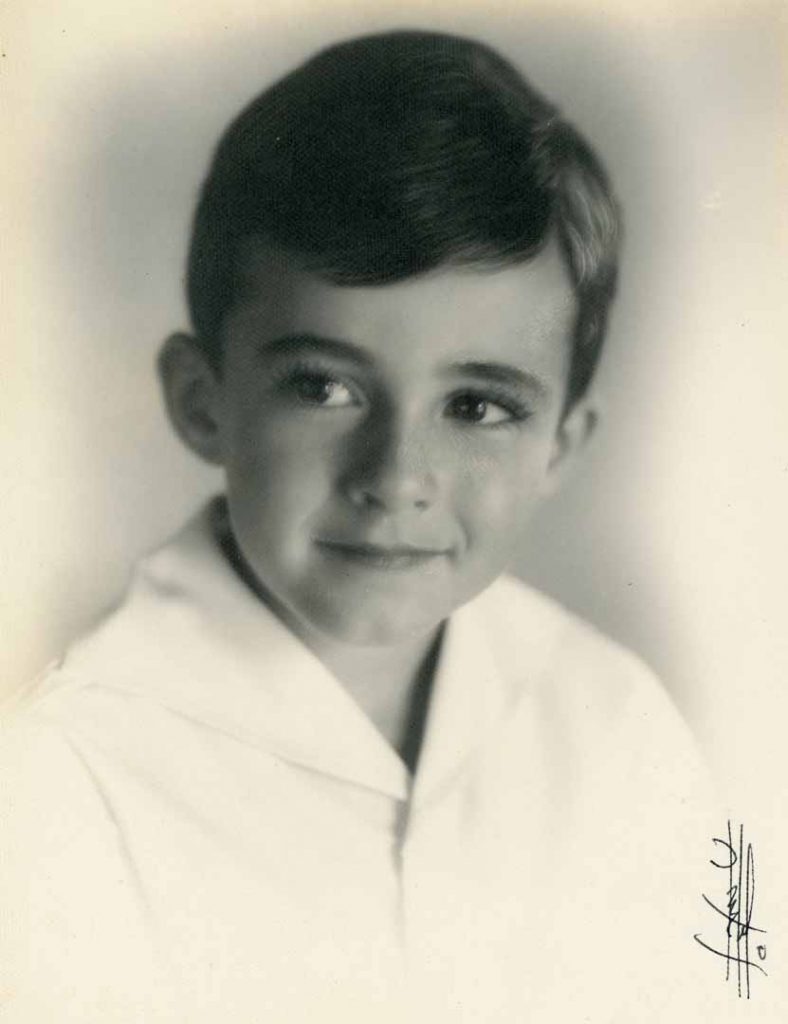

Born Robert Bentley Haines, he arrived on August 31, 1926, in Vallejo, California, to parents, Helen Donaldson Haines and John Meade Haines. His father was a Navy submarine officer and recipient of the Navy Cross for valor in combat during the raid on Makin Island (1942).

Baines lived a young life comfortable and sheltered from the Great Depression. His father’s mother was daughter of Thomas Francois Burgers – a Dutchman who was president of the South Africa Republic (1872-1877) and the last president of the Transvaal Republic.

He was the youngest of two sons. His older brother, John Meade Haines Jr., was an early homesteader in Alaska, eventually becoming that state’s Poet Laureate.

“I suppose my first memory of my family was when we lived in New London, Connecticut, about 1928 or 1929,” said Baines. My dad was stationed there, in the submarine service – the old S Boats, known as metal coffins.

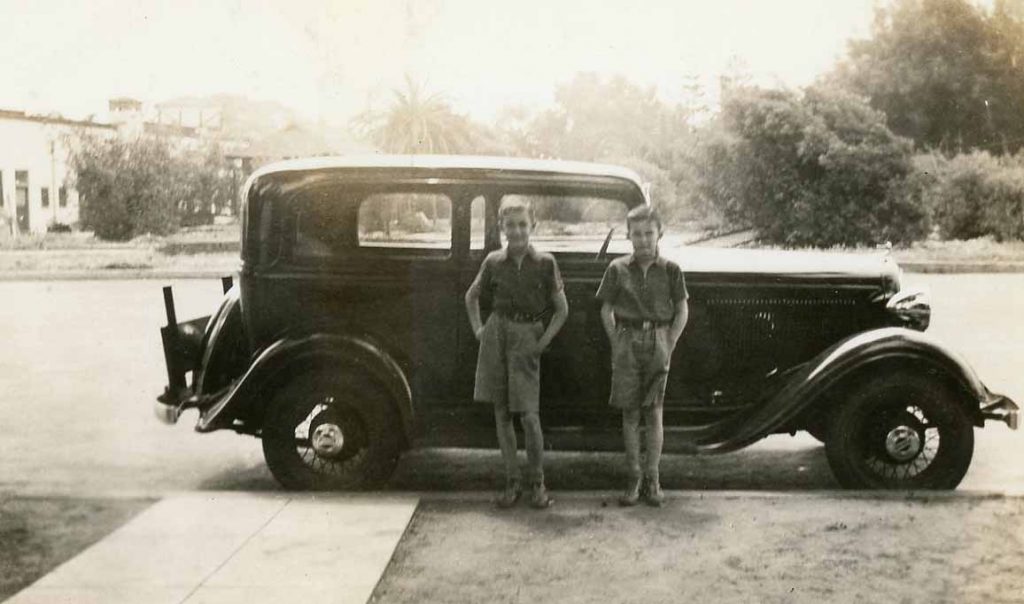

“I remember as kids we would put snowballs or little pieces of coal in the gas tanks of peoples cars as pranks,” he laughed. “They were old Model T and Model A cars back then. I remember we would also draw on the sidewalks and the neighbors called the police. I still remember the policeman coming and wagging his finger at us.”

Another early memory is of the 1933 earthquake in Long Beach. “My brother and I were in the back of the house. My mother and father were entertaining in the front. The house started to shake and the maid grabbed my brother and me, and we went out the back door. As we ran around the corner and headed for the street she reached out and grabbed me just as the chimney of the house next door collapsed and landed at my feet. She literally saved my life. Even though I was only seven or eight, I remember that vividly.”

His father at that time was gunnery officer on the USS Tennessee, a battleship. All the families were moved aboard ship because of the earthquake.

Baines’ father was Class of 1917 at the US Naval Academy. The Navy was his life. Of Dutch/English descent, his dad’s father was in the Marine Corps, as was his father before him. Both of the younger Haines brothers went into the service but broke family tradition by not making their lives military. They decided to spare their own families from moving to a new town and a new school every two years.

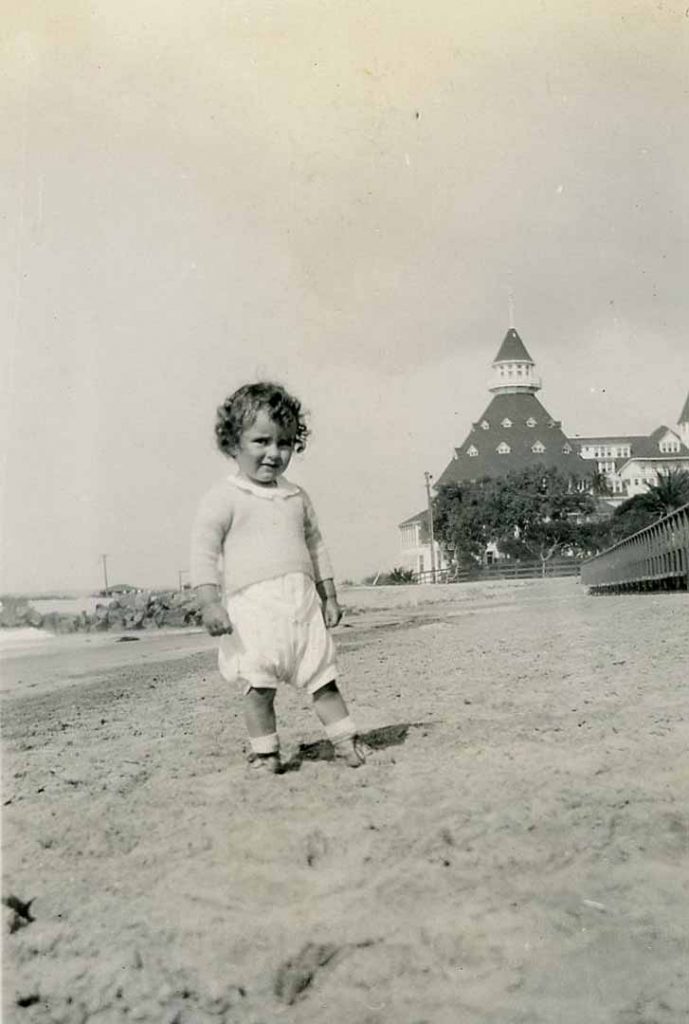

Baines’ introduction to Coronado came at two weeks of age, when his mother and older brother John moved here and rented a house on the 400 block of C Avenue. He attended schools in Coronado (CHS Class of ‘45), Bremerton, Washington, Honolulu, Vallejo and Washington DC.

His sailing and Jack London-esque lifestyle began in the 1930s while working for Sam Cobean, the dockmaster at the 1887 Boathouse in Coronado’s Glorietta Bay. He would sail the boats of the Rainbow Fleet for tourists and then clean boats, put up sails to dry, and do whatever was needed by the dock master.

High school was put on hold when Baines joined the Navy. He would return years later to finish and receive his degree.

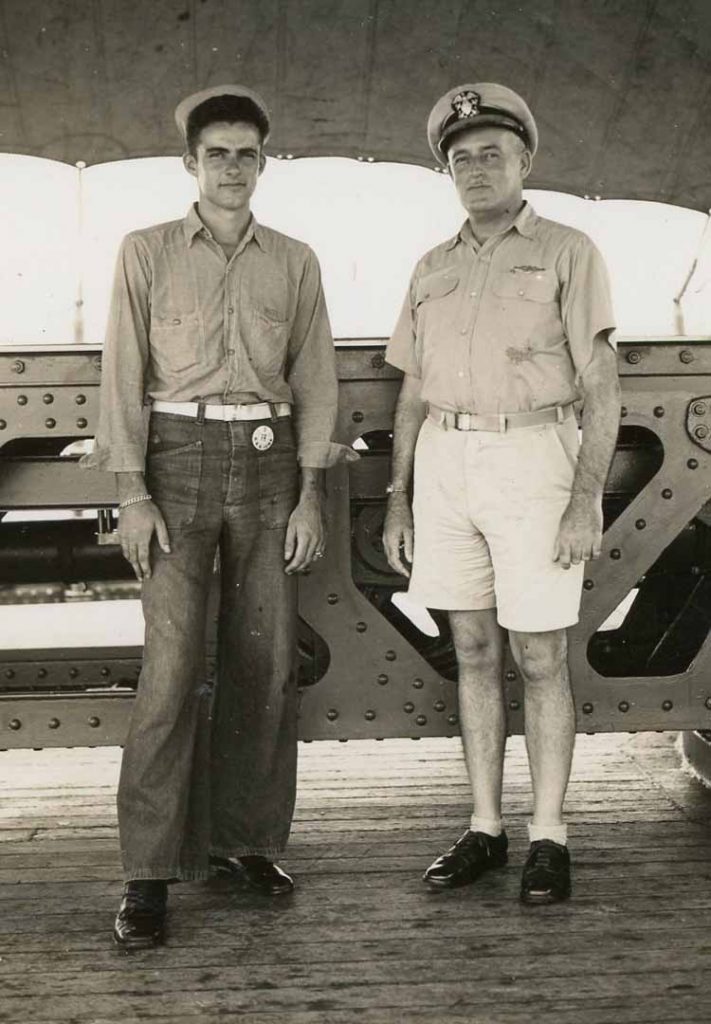

While his older brother became a sonar man on a Navy destroyer, Baines went through boot camp in San Diego before receiving orders to report aboard the battleship Iowa. During his two years in the Navy he was involved in the Battle of Leyte Gulf and bombardment of the mainland islands of Japan.

He witnessed the end of World War II from aboard the Iowa, which was anchored next to the battleship Missouri where the surrender took place.

“My battle station was a five-inch gun director that had a radar and range finder on it, with optical instruments for aiming the guns. So, I put that range finder right on the table where the signing took place, and didn’t think much about it at the time, but I saw the entire end of the war taking place before my very eyes – a ringside seat.”

After the war Baines left the Navy. He hung around with friends, took the ferryboat to San Diego to see Big Bands perform, and worked odd jobs at the El Cordova Hotel in San Diego and area gas stations.

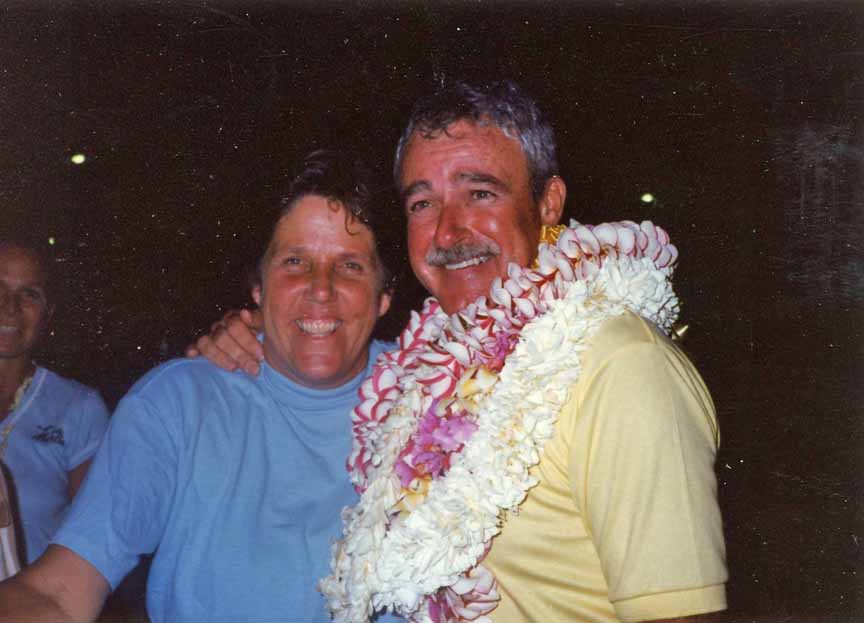

He joined Coronado Yacht Club in 1948 and began sailing in earnest. He crewed on the 64-foot yawl, Fair Weather in 1949, 1951 and 1955 for the hotly-contested TransPac race from Los Angeles to Honolulu. In 1974, he was navigator on Nick Frazee’s legendary 56-foot sloop Swiftsure.

During the 1975 TransPac he helped in an open-ocean rescue of a family aboard a sinking yacht that made headlines stateside. He navigated Merlin in 1981 and missed the TransPac speed record by 46 seconds. Baines owned Tabasco, a Cal-39, and for many years delighted in racing her in local races as well as cruises with family to Catalina.

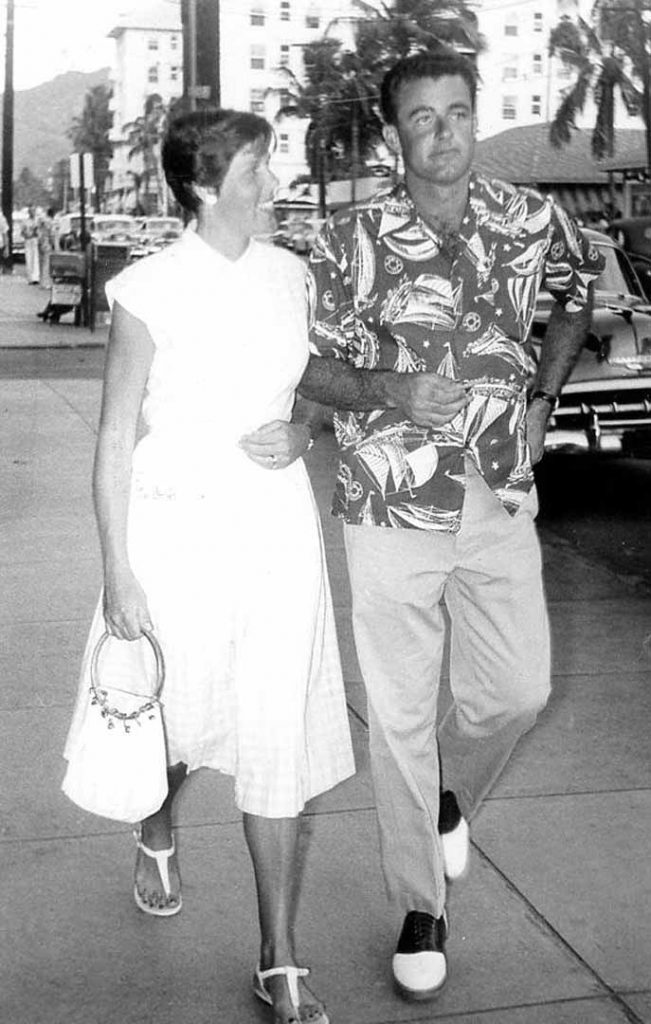

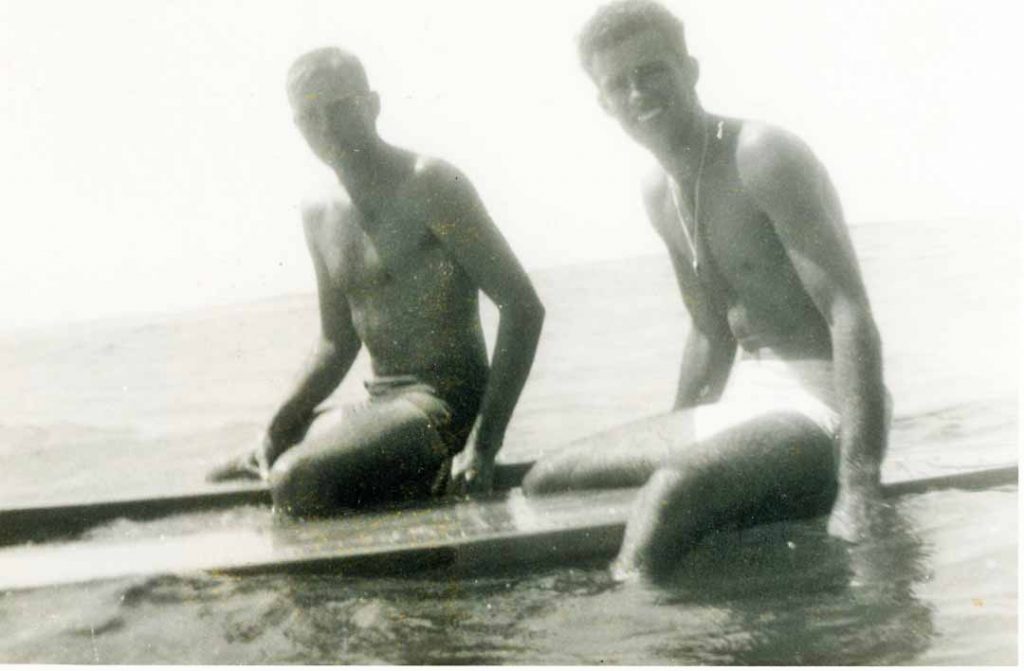

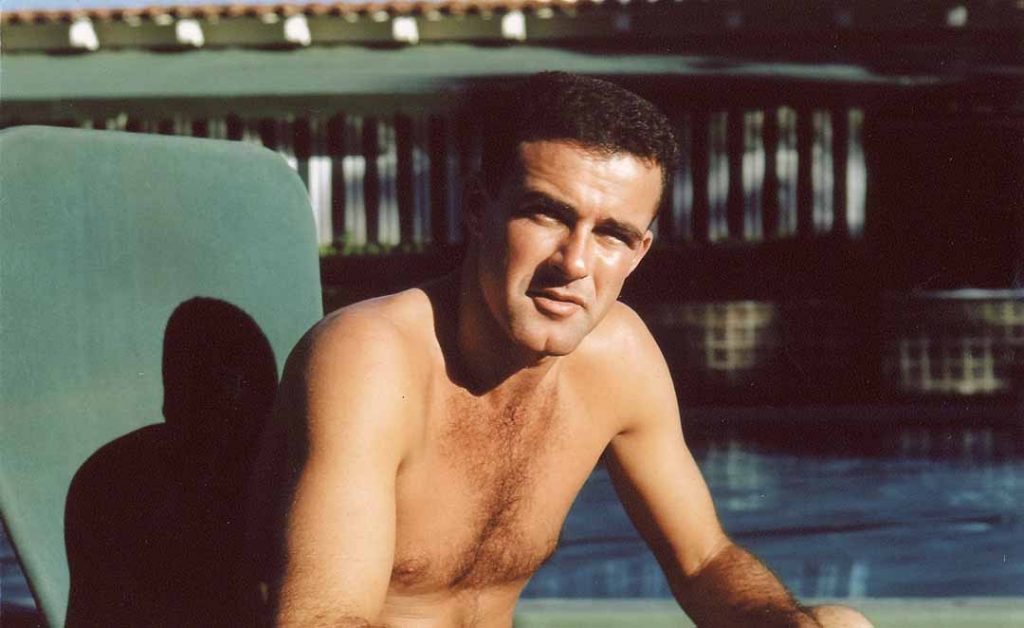

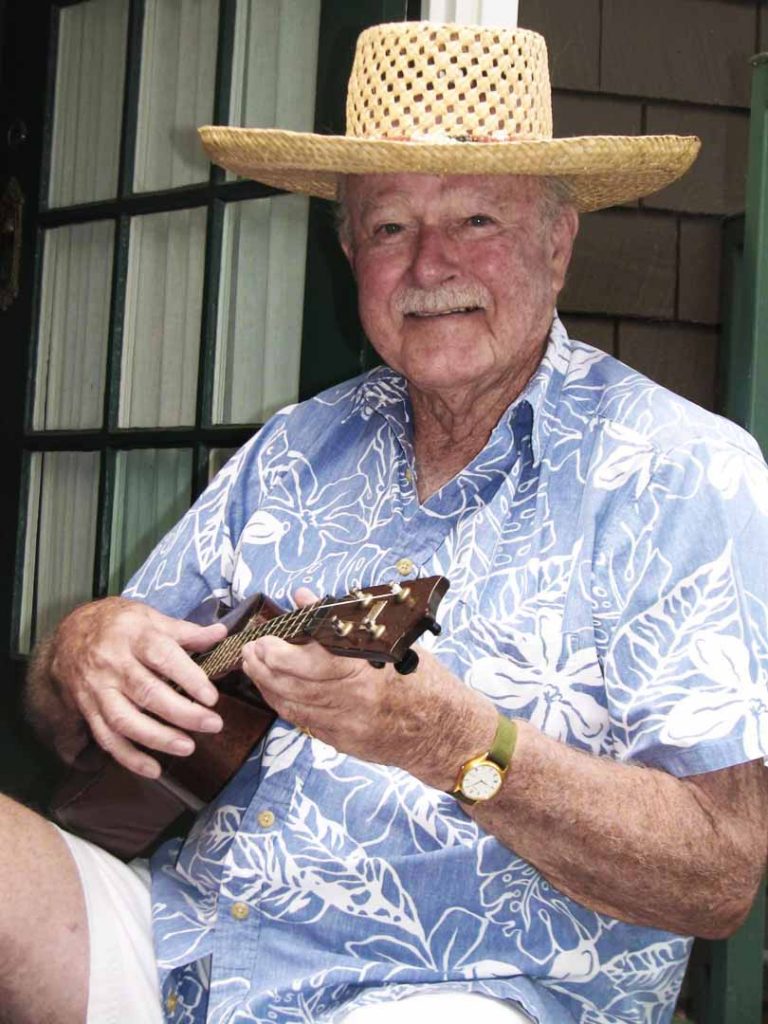

When they arrived in Hawaii after the 1949 TransPac, Baines decided to jump ship and stay in the islands. He had spent time there as a child, when it was the Territory of Hawaii. He accepted a position at the Moana Hotel, next to the Royal Hawaiian, where he and his pals could just roll out the door to the beach and the surf. While there he learned to play the ukulele.

“It was a great lifestyle,” he remembered. “But then the stevedore unions went on strike, and shipping was the only way the islands could survive. Suddenly they couldn’t get oil, food, and most of all, the tourists stopped coming. So I headed back to Coronado.”

In 1950 he heard that Scripps Institute of Oceanography was looking for deck hands. His life would never be the same. That was the beginning of a three-decade career and the perfect job for a young man looking for adventure on the sea. He worked his way up from seaman to mate, and then to captain. He was captain onboard several ships of the Scripps fleet but was often gone for months at a time.

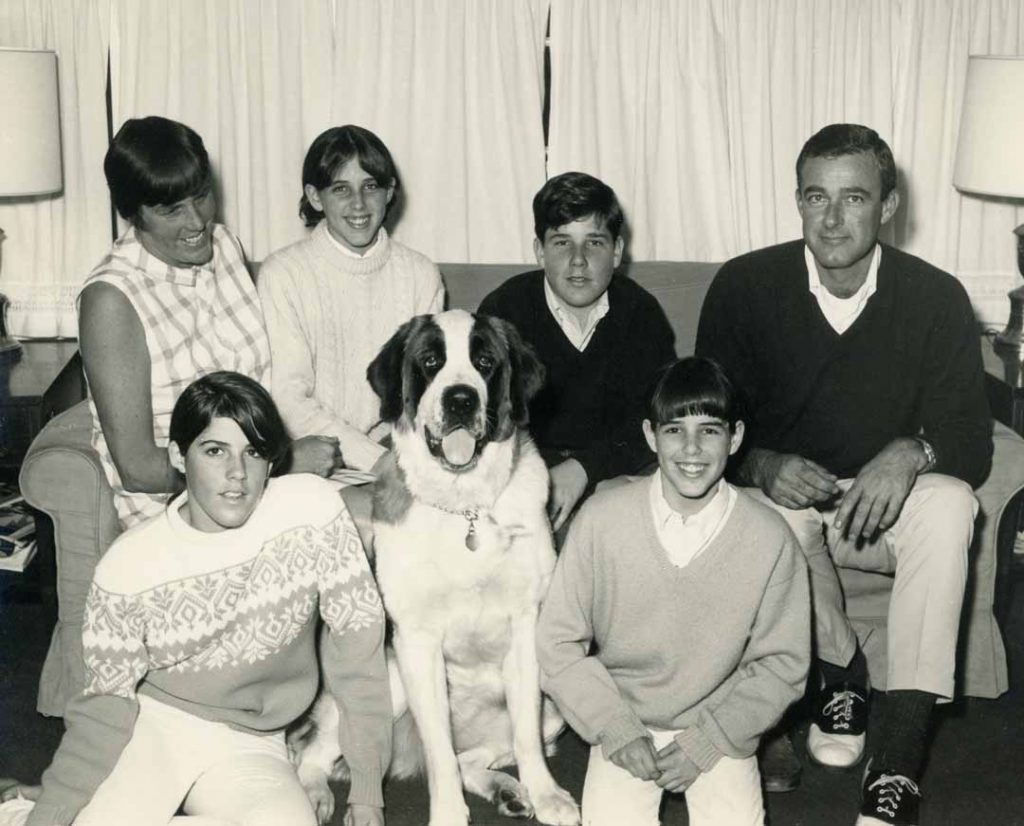

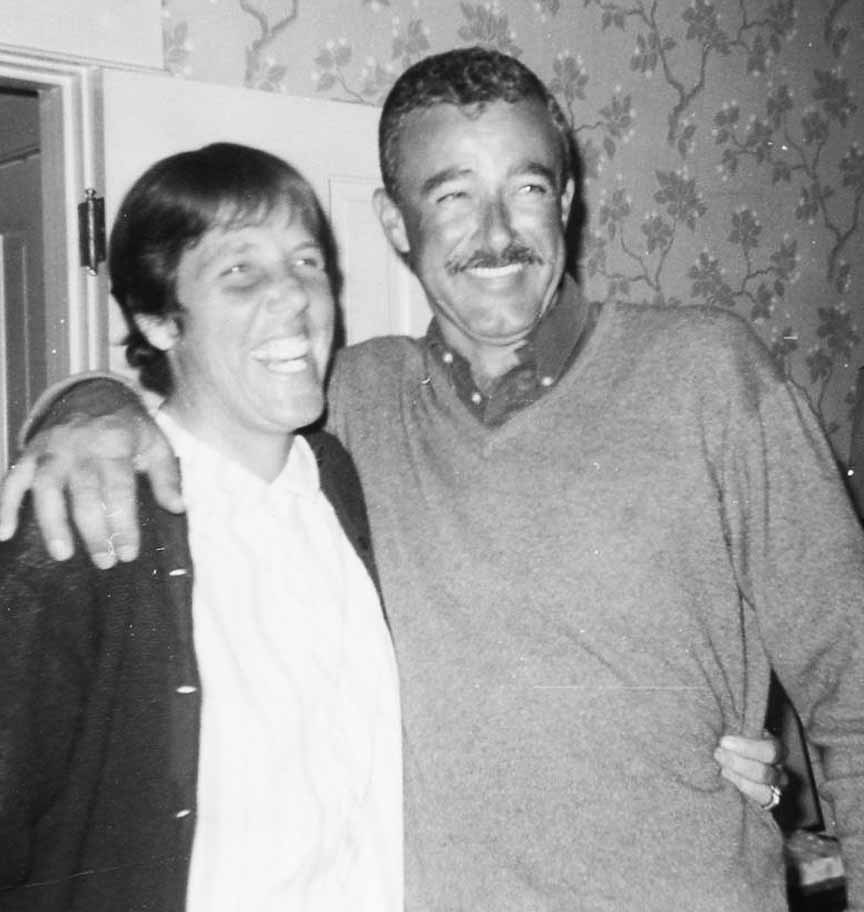

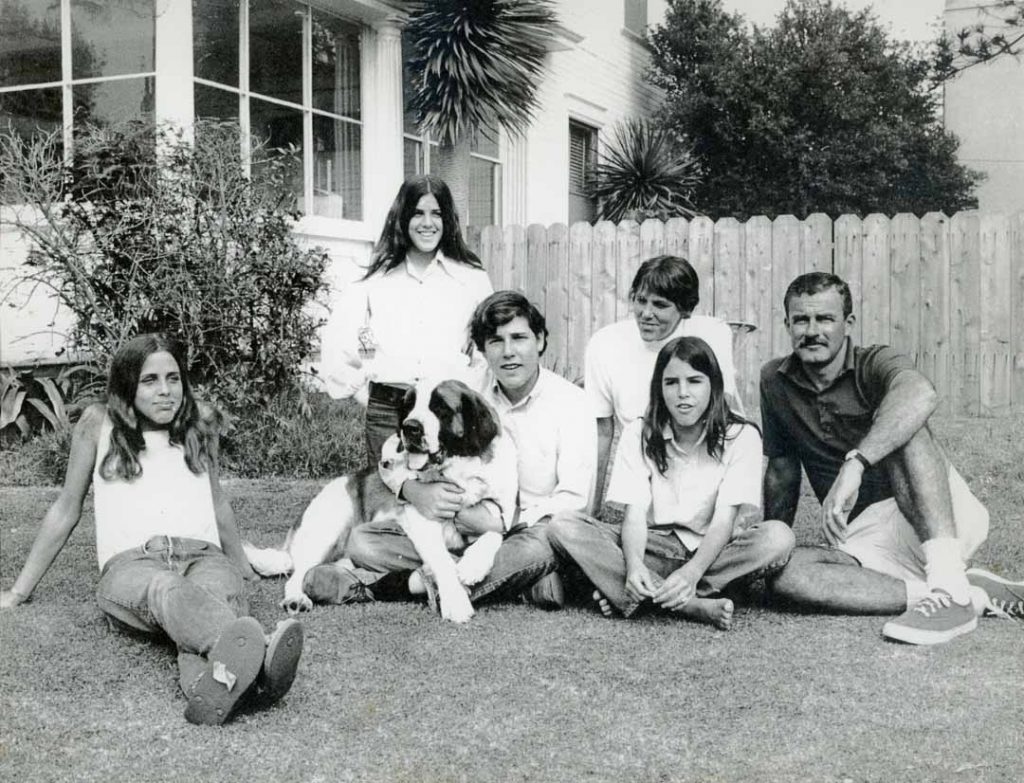

In 1952 Baines met his future wife, Barbara Reynolds. They married and had four children, living in Coronado while he spent sometimes as much as nine months at sea working for Scripps. They enjoyed 65 years together raising their family, traveling and sailing.

“Being at sea so much of the time was a hell of a burden on my wife Barbara,” he said. “So I decided to stop going to sea and try and do something on land.”

It was not a successful hiatus, and after a year he decided to return to the only thing he knew – the sea. Scripps was willing to take him back, but said he had to come back as a lowly seaman and start all over again. He did.

“That was a bit of a blow,” remembered Baines. “But I realized we had to eat, so back I went, and after four or five years I worked my way back to captain.” Many of his adventures at sea took place at the helm of the prominent research ship Alpha Helix.

Through his long 36 years at sea Baines had seen it all. He and his crews made rescues of distressed boaters at sea, conducted secret government work and mapped underwater disturbances that even included an explosive underwater volcano. In 1955 his ship was involved with Operation Wigwam – a government program designed to test the effects of a nuclear bomb on one of our submarines.

He has sailed through the eye of a hurricane, and survived numerous typhoons and tropical cyclones at sea. “There’s no wind in the eye of a hurricane,” he said. “The sun comes out and, while you still have big seas, there is no wind. As soon as the eye passes over you, you get hit again, and sometimes with winds close to 100 knots, and 50-foot waves.”

On one day distinguished newsman Walter Cronkite was his guest following a deep submersible dive; on another day uniformed South American Indians carrying automatic weapons, and having no grasp of the English language, would board his ship.

He was on the island of Mauritius, deep in the Indian Ocean, during the very tense Cuban Missile Crisis and nearly went mad worrying about his family back home, and not being able to communicate with them. He, like everyone else in the world, was certain the end was but a push of the button away.

He mapped ocean floors around the world and explored exotic and faraway islands such as Pitcairn, and even took his ship 1,500 miles up the Amazon River to provide electricity for a shore side laboratory. In the end, he contributed significantly to the research advancements at Scripps, and established an enviable record of having never lost a man at sea and executing his ships’ missions repeatedly and flawlessly over three and a half decades.

The Pitcairn trip came about from Baines being a HAM – an amateur radio operator. He had, over the years, shared numerous conversations with the great-great-great-grandson of mutineer Fletcher Christian, Tom Christian, who maintained a radio/communications station on Pitcairn Island. When the opportunity came to visit Pitcairn aboard one of the research vessels, Baines jumped at the chance, and spent time getting to know Tom Christian and the other descendants of the infamous mutiny of the Bounty.

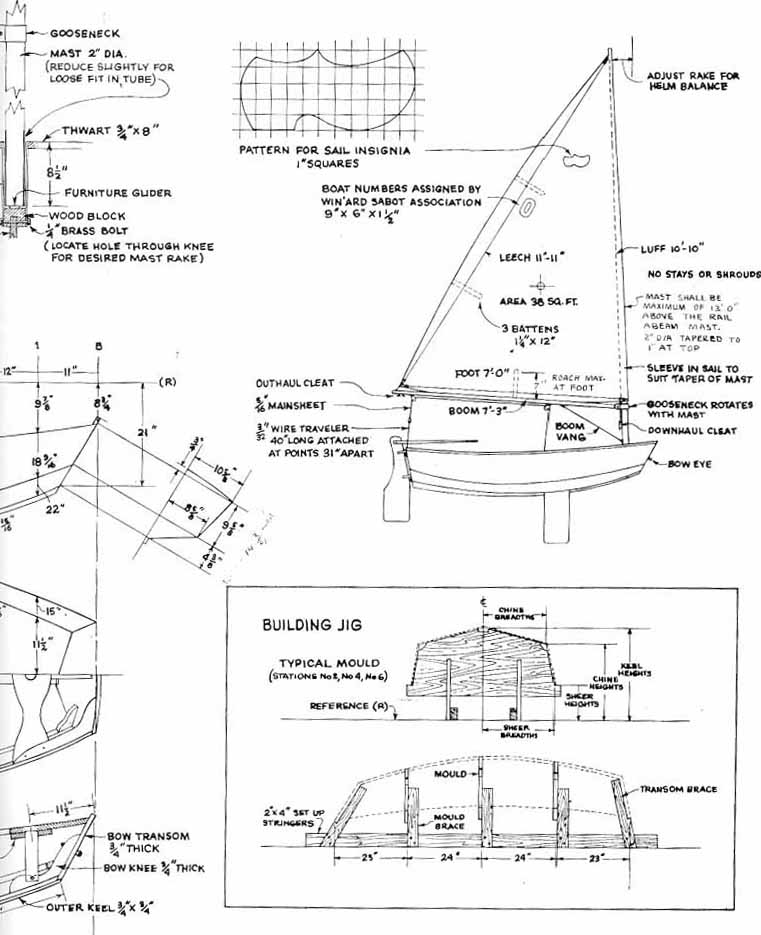

While on one of his lengthy Scripps trips, he took along hardware, materials and instructions on how to build a Sabot sailboat. He and another member of the crew built two of the small boats aboard ship. “It was a present for my young son Robbie,” he said.

“When I got back to San Diego I said, ‘Come on Robbie, we’re gonna go over and get your boat.’ I took him over to Scripps and introduced him to his new boat. We sailed it back to Coronado that day, and it was a very special sail. We named it Ropacabu,” Baines laughed. “Because that’s the first two initials of all my kids – Robbie, Pammy, Caroline and Bunnie.”

It wasn’t long before the 10-year-old Haines grew out of his Sabot. There were more boats, faster boats. In 1980 he, Rod Davis and Eddie Trevalyan, all from the Coronado Yacht Club, earned a berth on the Olympic sailing team aboard their Soling Class boat. That year America boycotted the Russian Olympics, but the boys sailed in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics and came home with a Gold Medal. And it all began in a little wooden Sabot, constructed in the hold of a research vessel at sea.

While missions varied from scientific to top secret aboard the ships of the Scripps fleet, one in particular made international headlines. In the mid-1980s, while transiting from Pitcairn Island to the island of Rapa Nui, scientists aboard the ship discovered an underwater volcano that was erupting.

Giant bubbles were rising four feet above the ocean surface and exploding – shooting out jets of gas and clusters of volcanic rocks too hot to handle. For a while the gaseous rocks would float. The crew on board the Melville, after a cautious approach, captured some of these hot, floating rocks and brought them back for study, gaining international attention throughout the scientific world.

In 1985 Baines retired for good. Modestly, he admitted to sailing at least half a million nautical miles in his lifetime, and probably much more. He made a dozen or more Equatorial crossings. In retirement he played golf, enjoyed his grown children, grandchildren and great grandchildren, but continually threatened to dust off the old ukulele one more time.

For the man who had spent more time at sea than ashore in his lifetime, Baines missed the sea right up until the very end. “It’s the solitude. The quiet,” he said. “The beauty of being at sea with no one around. It’s clean. It’s fresh. I’ve been a solitary man most of my life. I don’t know why. I don’t have that many close friends. But I have a wonderful family, and I enjoy their company very much.”

Would he go back to sea? “I would go back to sea in an instant,” he said, right up into his final years. “The sea has always been my home, and I suppose it always will be.”

Baines is survived by his wife, Barbara; children Robbie Haines (Amy) of Coronado, Pam Hardenbergh (Jamie) of Costa Mesa, Caroline Haines of Coronado, and Bunnie Hamilton (Jack) of Borrego Springs.

Also surviving him are grandchildren Brian Haines (Katie) of San Diego, Molly McKay (Bud) of Coronado, Clark Hardenbergh of Chile, Caroline Moghaddam (Zack) of Orange County, four great grandchildren and beloved friends Ryann Haines-Murray and Peter Huber.

Private family services are planned. Instructions for the disposal of his ashes he left on a yellow sticky note. At his request, his ashes will be spread half way between Coronado and the Coronado Islands.

On that yellow sticky note, he specified he wanted his son Robbie to place his ashes at a particular longitude and latitude, where an ocean eddy would keep him forever swirling in the waters he loved to sail, near the family he loved so deeply.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Coronado Maritime Foundation Junior Program, “In memory of Bob ‘Baines’ Haines,” 1631 Strand Way, Coronado, CA 92118.