Editor’s Note: Buzz Adams is the author of this letter and has given permission for it to be shared on The Coronado Times.

Yesterday was an anniversary of sorts. The 42nd year since the last US servicemen died in Vietnam. One of the last was a Coronado guy, Marine Capt. Bill Nystul.

The Last To Die

There are over 58 thousand stories on the black granite wall of the Vietnam memorial, none of them with a happy ending.

Just before midnight, April 29 of 1975:

“Pull Up, Pull Up, Pull up!”

Blared the loudspeaker on the aircraft carrier.

Then a flash of light in the dark murky water, as the CH46 Marine helicopter slammed into the South China Sea just off the coast of South Vietnam.

Most Americans had put the War behind them. I had been back over six years. I was doing okay, better than okay really. I lived in an apartment on the beach in Venice, California. I worked in Century City, for the worlds best known accounting firm, was a CPA and had graduated UCLA a couple years before. I’d traded my tattered Marine Corps cammies and scuffed up combat boots for Pierre Cardin suits and tasseled loafers. I carried a Monte Blanc now, not the automatic shotgun. Post Traumatic Stress seemed to have missed me. Sure there were the little things, a startling sound, a moment alone when a face would flash in my mind, along with that heavy sad feeling, and then be gone as quick as it came. The fact my eyes picked up little movements, instantly locking on them, capturing some animal’s movement in the bushes, seemed humorous. The agitation and need for movement was no big deal, I ran seven miles on the beach, each morning. I was fine, those memories, pushed far back in my mind with the door nailed shut, were less and less potent with the passage of time.

The American troops were out of Vietnam in 1972, only a small handful of advisors and embassy guards remained. We’d abandoned the Vietnamese, no two ways about it. We’d negotiated an end to our participation and then reneged on the promises we made them, and let the communists take over. Millions of people would die in the next few years. But we were out of there. The North Vietnamese knew they could move on the south, even though they’d agreed not to in Paris. And move they did, taking one province after another. As their forces neared Saigon, the American Ambassador had detailed plans for the evacuation of Americans and important allies, those Vietnamese who had been most helpful and would likely be killed quickly by the communists. There were prearranged landing strips in the Saigon and a special signal to be played on a local radio station when the evacuation would happen, the signal, Bing Crosby singing White Christmas. The Ambassador had his orders, but he would not comply. He didn’t issue instructions or implement the plans. He sat in his office and did nothing as the North Vietnamese forces surrounded the city. He helped insure the coming chaos.

As the situation got more dire, both Americans and Vietnamese converged on the Embassy. The American admiral, in charge of the flotilla of warships waiting off the coast, had had enough and ordered his forces to begin the evacuation. Bing Crosby sang, but no one came to the waiting helicopters with their Marine guards. Everyone was at the Embassy, where landing space was limited. Marine helicopters began making run, after run, taking people from the embassy grounds out to the waiting ships. Other transport barges began loading people at the shore and moving them to safety. It was slow and people began to panic. Anyone with a plane or helicopter, which included all the South Vietnamese pilots, military brass and their families, loaded up and took off heading for the American ships. Those in the flotilla described the hundreds of coming aircraft as a swarm of locust heading in their direction.

My high school years were split between Fitch High School in Groton CT, and Coronado High in California. I’d transferred to Coronado for senior year. Bill Nystul and his brothers, were wrestlers, on the Coronado team. I tried it, but balancing upside down on my head and heels, to strengthen my neck, convinced me, it wasn’t my sport, but it was theirs, and they were great at it. Coronado is an island. Half is a pretty beach community and the other half is a Navy base. Forget Kitty Hawk, real flying, military flying, began there.

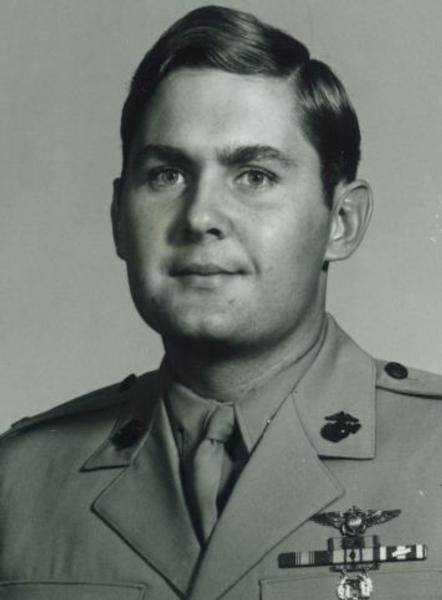

Years before, a Navy jet, coming low over the Coronado beach, had problems and crashed in the sand. A young Bill Nystul jumped barefoot, up on the wings, of the burning plane, and tried in vain to help the pilot get out. Bill’s house was a block away. He had grown up on the beach, surfing and watching the planes passing over the red roof of the Hotel Del Coronado, coming down the beach and landing on the airstrip just beyond the chain link fence. He would become a Marine pilot, after graduating San Diego State. By April 1975, Bill was a Captain, had taught flying to other Marines, in Pensacola, was married, and had a two-year old son. He’d just been transferred to Okinawa, Japan and was being reacquainted with flying the CH-46 Marine helicopter when it happened.

Bill, his copilot and crew, flew rescue missions for hours that day. When the swarm of planes and helicopters came out from South Vietnam, many crashed in the sea and US helicopters worked all day and into the night attempting to pluck people from the water before they went under. The situation was intense with planes just missing the rescue helicopters. On one carrier Vietnamese helicopters were allowed to land, let off their passengers and then were ordered at gunpoint to ditch in the sea, and be picked up by boats crews. There wasn’t enough space on board the ships for all the aircraft. Many people were dying as inexperienced pilots crashed in the sea or onto the ships.

As night came, the lights of the many ships were visible, but the water and sky were black. Inside the rescue helicopters it was disorienting as the lights in their cabins made the outside even darker. Bill’s helicopter was running low on fuel and was headed back to the ship, when the crew chief yelled to turn right to avoid another Vietnamese plane. They swerved just in time, and Nystul commented, “Someone is going to die out here tonight.” As they headed back around to land for more fuel, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. The crew chief, a machine gunner, was watching out of the window when he noticed the Hard Landing light come on, then the booming loudspeaker from the nearby aircraft carrier, ” Pull Up, Pull Up, Pull Up “. The next thing he knew, he was under water and in great pain. The helicopter had hit the water so hard, his left leg was shattered above the knee and the bone stuck through his flight-suit, his other leg was dislocated at the hip. The chopper sank immediately. The crew chief credited his underwater crash training with saving his life. He inflated his life vest and made it to the surface, along with the other machine gunner. Both pilots were missing. Their crash was witnessed by hundreds of sailors and Marines on board the ships. Rescue helicopters were there within minutes. Neither, Bill Nystul nor his copilot were ever recovered. They were the last to die in the Vietnam War. A burial at sea was held the following day, with some of their gear serving as the bodies.

It’s comforting to think that those we knew, who have passed, are watching down over us. It’s less comforting to think about the ones who died way to early, serving their country, then watching loved ones enduring their loss, and finally moving on with their lives without them.

Editor’s Note: Buzz Adams is the author of this letter and has given permission for it to be shared on The Coronado Times.

—

Related: Copter pilot one of last killed in Vietnam