He served his country proudly in Korea and Vietnam as a pilot in the US Navy. In 1967, at the age of 38, Captain Mel Moore was shot down over Vietnam. He spent 2,185 days in confinement at the notorious Hanoi Hilton — one week shy of six years. He served with other POWs who would later live out their lives in Coronado, men like Jim Stockdale, John McCain, Harry Jenkins and Ed Martin.

As a prisoner, he suffered extreme torture at the hands of his captives. And yet, he not only survived, but found a way to help those around him, despite personal risk. Mel Moore died this week at the age of 91 years, in Coronado, with his wife Chloe beside him.

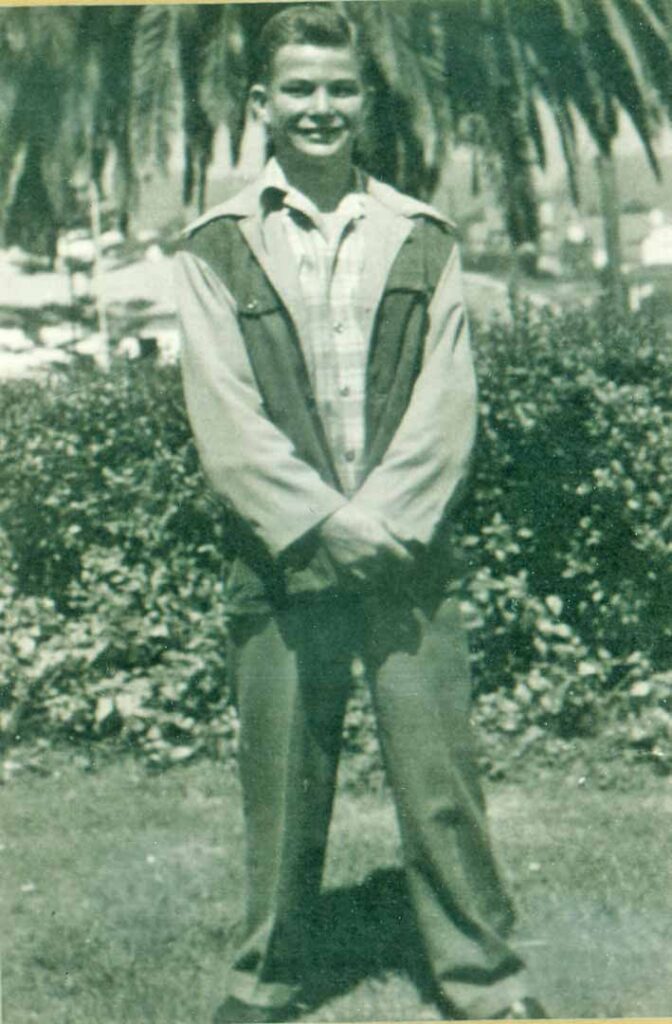

The oldest of two boys, Mel was born June 2, 1929. He lived in the Bay Area (Oakland & Berkeley) most of his youth. His younger brother Terry and he were nearly four years apart. The family enjoyed many camping/fishing trips together.

Their parents were Lydia Burr (Robbins) and Ernest Melvin Moore Sr. She was a couture seamstress and he was a banker. It was enough to get them through the Great Depression without too much sacrifice, recalled Mel. “I was born the year the Stock Market crashed, but I had a very happy childhood. From the age of eight, my brother and I would walk ten blocks to the movie houses in town every Saturday. I always loved the cowboy movies. Actor Tom Mix was my favorite.

“My childhood was a lot of fun. I had lots of friends. Terry and I didn’t pal together at all, but there were always lots of friends around. I played sandlot football up until high school. I wasn’t a big kid but I was fast.”

Mel’s family dates back to the first European colonists in America. Other ancestors came from Ireland and Germany in the early 19th century. Aaron Burr was a distant relative, but not one they talked about. Burr was this country’s third Vice President and renown in history for killing his political opponent, Alexander Hamilton, in a pistol duel.

During the Depression, Mel’s father’s parents moved to Waterford, in the San Joaquin Valley. Mel would often go there and pick fruit during his teen years – something he always looked forward to.

From an early age, Mel desired to fly. In order to get into the navy flight training program, he had to have two years of college, so, after high school, Mel attended the University of San Francisco. After a year and a half his grades were just average. As he put it, “my grades weren’t very special.” He felt he was not getting the education he was mentally capable of. Meanwhile, his father decided he wasn’t going to pay for his college education any longer if all he was going to achieve was a ‘C’ average.

Mel’s desire to fly was not diminished. He worked hard to make his own money, and he attended the last semester required for flight training through an extension program at Cal Berkeley.

Mel’s love of reading contributed to his life far more than education and homework seemed to do. Those were things that traditional schools demanded, but it was Mel’s insatiable appetite for books that made the difference in him as he grew into adulthood and became a pilot.

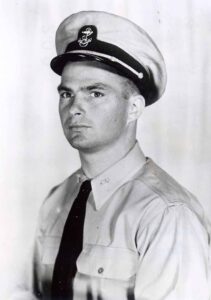

Mel signed up for flight training the day the Korean War started but had to wait a year before they called him up for active duty. “I knew nothing about war and glory, I just thought it would be glamorous to fly airplanes.” Many of Mel’s ancestors have seen war: the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Civil War, WWII and the Vietnam Conflict. Mel was commissioned as an Ensign in May 1952.

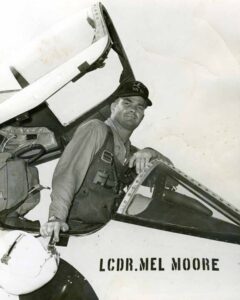

He was in carrier squadrons for both wars. Some of those earlier flattops were from WWII and had straight decks, which made landings difficult at times. But he adjusted, and became one of the best pilots on his carrier in Vietnam. He was executive officer of his squadron on the USS Ticonderoga.

In Korea, as a young ensign, he recalled being shot at, but said it didn’t bother him much. Then, in Vietnam, as he became older and his rank grew to that of commander, things like “chances and odds” were more a part of his thinking and preparation.

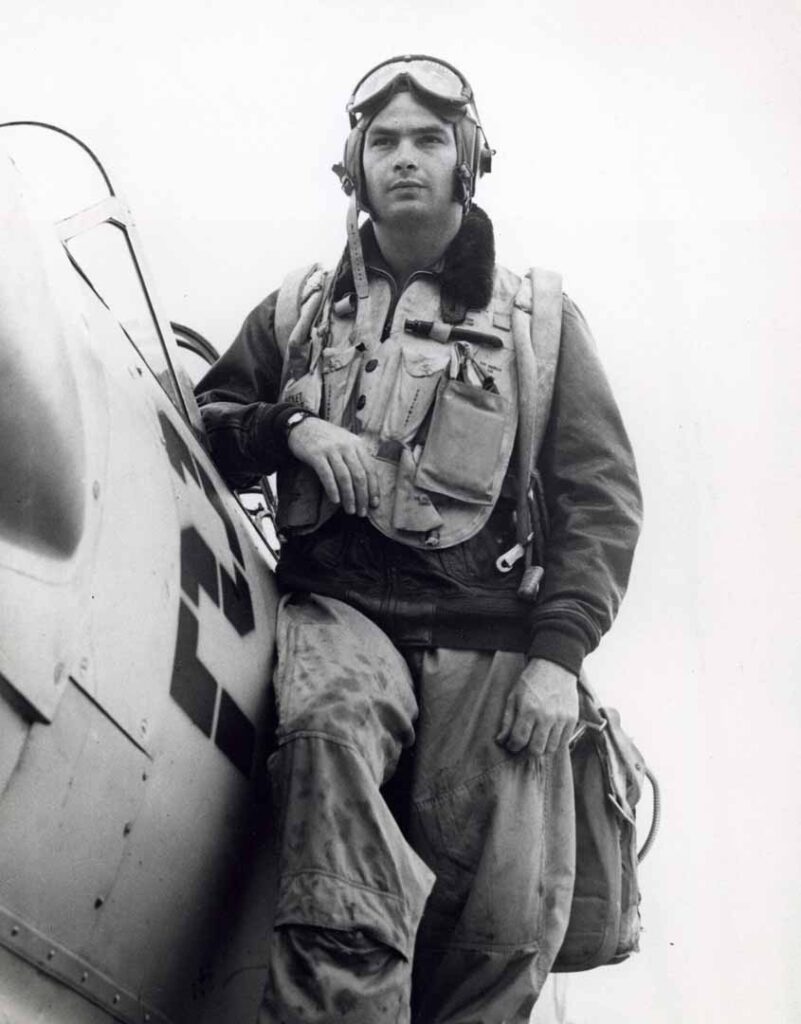

Over his career in the navy, Mel flew everything from the propeller-driven SNJ training aircraft to the jet-powered A-4E Skyhawk (in which he was shot down in). Others included the F-80, Corsair, the Grumman series (F-9), and many more.

“We always tested the limits and we knew what those limits were”

“Flying was my education,” Mel often said. “It was a skill to be learned, and it also had limits of what the aircraft was capable of doing and what I could do in an aircraft. That experience taught me the lessons of what is extreme in life – again, what you can do, what you can’t do, and what you can get away with. In that sense, it was an educational experience for me. I learned not only what mechanical things are capable of, but also what human beings can do. Of course, we always tested the limits and we knew what those limits were. But there was nothing to achieve by going beyond those limits.

“To me, you learned and worked hard to achieve the right to be in that seat, flying that jet. It was wonderful up there, of course. It’s been likened to being above the clouds and shaking the hand of God. That’s the way many describe it.”

Mel easily broke into the poem at that moment, “High Flight,” by John Gillespie MaGee, Jr., that ended with, “… reached out my hand and touched the face of God.”

On March 11, 1967, Mel was flying a seek and destroy mission designed to take out fixed and mobile missile launchers in North Vietnam, a notorious area known as the Iron Triangle. He was literally using himself and his airplane as bait to lure ground fire from the North Vietnamese.

Mel’s Silver Star Citation touches on this mission as it describes how Mel demonstrated, “…resolute courage and outstanding airmanship enabling him to personally evade eight surface-to-air missiles directed at his aircraft, and then to execute determined and deliberate attacks, which neutralized two separate missile sites threatening the strike group.”

In other words, Mel’s job was to be the target, to take the heat, and free the other pilots on their mission. These were risky missions – only the best pilots would take them on.

The Citation, after the fact, continued to say, “The successful execution of this mission attests to Captain Moore’s superb professionalism and leadership, his inspiring courage in the face of grave personal danger, and his selfless dedication to duty. His actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

On this day, however, as Mel approached his target, the air around him became filled with “telephone poles,” as he described them – land-based missiles that looked like telephone poles flying at you from multiple directions.

Out-flying them wasn’t a problem if you saw them coming. But, if you didn’t see them, even though you knew they were coming, they could go off within 50 feet of you, and that’s what happened on this particular mission.

“All of a sudden my plane exploded”

“I lined up to take out a missile site. I had dodged so many telephone poles previously, and it was rare they made contact with you. But I had my weapons honed in on the radar of that missile site to be sure my weapon hit it. I saw the missile in front of me but not the one behind me.”

Mel had his finger on the trigger, needing just a moment longer to take out his target. “All of a sudden my plane exploded. Instantly, my aircraft was a sieve. All my gasoline streamed out within a minute. If another missile came, I couldn’t dodge it and I couldn’t make it back to the water. So after about 45 seconds, which was probably too long to stay in that plane, I ejected.”

Mel’s canopy blew away and a seat rocket shot him and his seat out of the disintegrating airplane. He separated from his seat and his parachute slowly began to drop into a flooded rice paddy below. He could see people running towards his parachute. Once on the ground, he surrendered to a 17-year-old peasant girl with a handheld sickle.

In that regard he was lucky. Some pilots were attacked, beaten, their clothes ripped off and dragged mercilessly to a prison, where the beatings continued in the extreme. Sometimes those people on the ground were filled with rage from earlier airstrikes that killed family and friends. Those beatings were much worse than what Mel experienced when he hit the ground.

Mel was blindfolded, stripped to his underwear and force-marched barefooted for four hours through the rough terrain. While in their village, little old ladies would come up and beat him. He ended up at what became known as “the Hanoi Hilton,” a former French prison built to house Vietnamese. The cells were extremely small, cold and suffocating.

His experience began sitting in front of three Vietnamese officers behind a table. They asked him for information about his squadron and mission. “Name, rank, service number and date of birth were all we were required to give our captors,” Mel resolutely explained.

“So, I answered that twice. That’s when they tortured me the first time. It was sheer physical pain as they tied my hands behind my back, shackled my ankles, and hoisted me by my arms to the ceiling. No one could withstand the torture, try as we might. I was there three weeks before I saw another American. I was tortured Saturday, Monday and Wednesday, as they sought different information from me each time.”

“They broke us again and again”

Torture included cuffing his hands behind his back. U-bolts were secured to his ankles with a six-foot metal rod. Ropes were tied tightly around his upper arms, and then his captives pulled his head to his ankles, or lifted him by his secured wrists and forearms, causing extreme pain.

“They broke us again and again,” said Mel. “No words can describe that torture, or the pain we endured or succumbed to. They forced us to talk, to write. Torture was designed to break us, and then to convert us to Communism. They neglected to accept that we were, as pilots, all educated men, and the Communist Doctrine was ridiculous to the educated man.”

When asked if resistance was an option. Mel said resistance was a learned conduct to save honor. But when they applied torture and pain, nobody got away with just name, rank, service number and date of birth. “Nobody did get away with it, much as we tried.”

The irony of training versus reality while in captivity was not lost on Mel in hindsight. “They taught you at survival school stateside to only give minimal information, but nobody got away with that in actual captivity. Everyone can be broken. All of us were broken in one sense or another. You resist, then you give them something. Then, to salvage yourself, you go back to resistance mode.”

That year was 1967. Mel was 38, married, with three young daughters at home. He was flying in the most technically advanced aircraft known to man and he was loving it. Suddenly, and without warning, Mel was forced to the ground, where he served 2,185 days, 312 weeks – one week shy of six years. He would later sum that up as, “I served longer than most, but not as long as some.”

How he dealt with torture and solitary confinement could be a study in the human spirit; how man finds strength even when there appears to be none.

“I was in solitary for two years, but not all at the same time. I was in solitary for 17 months, then put with someone else, then back into solitary. Probably 22 months total in solitary confinement.” How Mel dealt with solitary is another story altogether. “It didn’t bother me to be alone, because I had enough education to go back and remember in detail all the things I learned in college.

“It has never, ever bothered me to be alone. Even in Vietnam, solitary confinement was not the punishment the Vietnamese thought it would be, to make me change. It didn’t bother me to be alone at all. I had just gotten out of the Baccalaureate program in Monterrey, and in solitary I forced my mind to rethink every one of those courses. I literally rehashed all the schooling I had while I was in solitary.”

“…hatred served no purpose”

Of course, to hear Mel tell about solitary confinement today, he makes it sound like solving a mathematical problem. It was certainly more than that. He was a particularly strong young man, highly educated and fully aware of his situation and the players in this horrid game – his captors and fellow prisoners.

Most notably, he refused to allow hatred to influence his attitude. While a lot of other pilots harbored extreme anger and hate for their captors, Mel made a conscious decision that hatred served no purpose.

The cells in which prisoners were held were built by the French, to house the Vietnamese, a much smaller people. “You couldn’t even walk in the smallest cells,” said Mel. “Therefore, our everything was small. Some were designed as punishment cells. Many of the bunks had leg irons at the bottom, which served as extra punishment – usually for not doing something the Vietnamese wanted. It was a painful option without having to torture you again.”

Next to Mel’s cell was a prisoner named Ben Pollard. They couldn’t see him, but could hear him screaming all night long in pain, hallucinating and yelling for his wife Joan.

Mel didn’t know Pollard, but decided he had to do something or that prisoner would be dead. At great personal risk, Mel called for his guard. Depending on the mood of his captor, he could have received a vicious beating just for talking. Mel bowed to his interrogating officer and uttered, “Bao Cao,” the greeting prisoners had been taught when in the presence of their jailers. Mel asked if he could move in with the dying prisoner in the next cell.

“Well, they didn’t want the other prisoner screaming either, and I knew it wasn’t unusual for someone to take care of someone else who was wounded – prisoners helping prisoners. When I went into Ben’s cell he was black from the waist down from internal bleeding, covered in his own feces. I made him get up. I told him he either got up or died. He took me literally.

“I cleaned him up and stayed with Ben for three or four weeks, until he could take care of himself. We survived the Hilton, but Ben’s dead now. He always said I saved his life. I probably did.”

Mel went on to describe the conditions and climate during captivity. “The leaders of our American prisoners had already been thrown into the Hanoi Hilton when I arrived in March of 1967. When I was finally moved in with other people, they were all there, many who would live out their days in Coronado – Jim Stockdale, John McCain, Harry Jenkins, Ed Martin, etc.

“The senior officers were thrown into different cells, the Vietnamese knew they were the ringleaders because of the codes and communication created between the prisoners. We were all together for about a month, and then they were moved into a place known as Alcatraz, to separate them from the other prisoners.”

The Alcatraz Gang was a group of 11 POWs considered a threat by their captors for their resistance efforts. The name “Alcatraz” was coined by ranking prisoner, Jim Stockdale. These prisoners were shackled at their ankles nightly, in 3×9-foot, windowless concrete cells. The room lights were kept on around the clock.

No matter what your rank, or what part of the prison you were held captive in, you had to bow to the guards when they passed, as Mel referred to previously. Everyone did that, at one point. But it was common to see how little of a bow you could get away with, Mel said. “It was different when they took you ‘downtown,’ and foreigners were around, to show you off. You either didn’t bow, or did a partial bow to see what you could get away with, but not in front of outsiders, only in front of the prison command.”

“If [we] could only come home with one thing other than [our] lives, it was honor”

Many memories survive from those six years in captivity. Mel remembered getting to know Stockdale when they roomed together for a couple of weeks, something he is most grateful for today. He remembered dates, times, numbers. Those little facts and details have never left his mind.

Pilots share a certain esprit de corps, as they have since man first took to the air – a feeling of pride and fellowship. In captivity this fellowship was enhanced. They were a well-schooled, highly intelligent lot, and did their best to take care of their own. If they could only come home with one thing other than their lives, it was honor.

“There were a few guys that just gave up,” Mel recalled. “Nine prisoners out of 484 of us died in jail. Then, when they brought up enlisted men from South Vietnam, it was totally different. Most of these men had little formal education, some had failed to even graduate from high school. Most were drafted. There was a marked difference between those men and the officers who came from the sky. This affected their conduct and the mood of the prison greatly.”

“All those dreams I had in prison about my family and my countrymen have actualized far beyond my dreams.”

Once home, Mel continued to examine and analyze his thoughts, memories and experiences – both good and bad. “It is very important that those six years of my life leave no feelings of bitterness within me,” he said in his naval biography. “I have worked hard to make those bleak years contribute something of value to me as a man – as a human being. I have succeeded to some degree.

“The simple process of mental exercise, especially in solitary confinement, has helped me arrive at some simple basic truths about life and my place in this structure of human interaction. I know what freedom is because men attempted to deprive me of it. I have found freedom to be a mental attitude: you can be free even though confined in a cell if you set your mind to that task. Then, you learn that freedom of speech is as much an obligation as it is a right.

“Life is very beautiful for me now. All those dreams I had in prison about my family and my countrymen have actualized far beyond my dreams. I have dealt with destruction and know deeply the tragedy of war.”

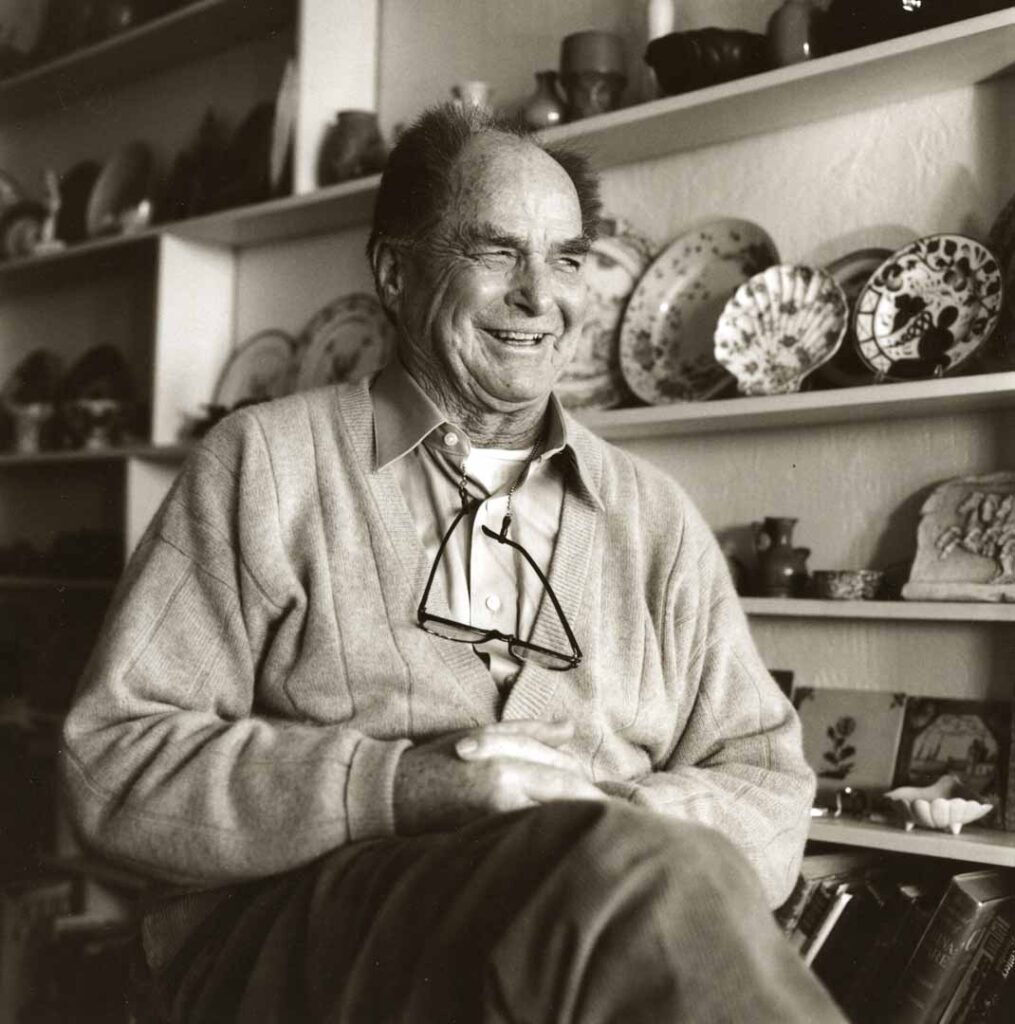

Captain Moore was released with the second wave of POWs on March 4, 1973. Once home, he had some catching up to do. He had to rediscover his family and his life. He continued to read everything he could get his hands on, and worked with a number of groups and institutions lecturing and teaching. He and Chloe separated for a time, and Mel took up an isolated way of life in the Bay Area. It, in hindsight, may have been part of the healing for a man who had been through six years of captivity, torture and solitary.

He gave up alcohol. “I stopped drinking in 1987,” he said proudly. He and Chloe got back together and lived out their days in Coronado. Mel continued to emphasize education until the very end, whether in civilian life or through the military. He believed strongly that education made all the difference in the world at how you looked at things and reacted to them.

Mel served as commanding officer of the attack transport USS Paul Revere and then as commanding officer of the amphibious assault ship USS New Orleans until his retirement from the Navy Dec. 31, 1978.

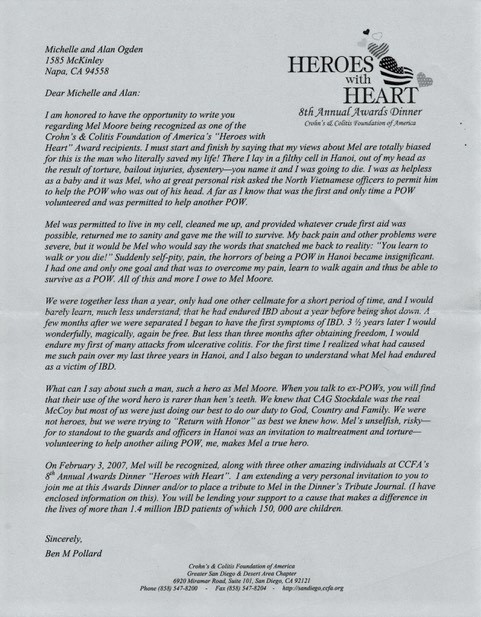

In retirement, Mel entertained his fascination for collectibles. He collected cameos, rare pearls, Asian porcelain, antique marbles and Chinese snuff bottles. He painstakingly catalogued his collections. He was on a lifelong quest for knowledge and proudly reaped the rewards of that quest until the very end.

“I’ve never told anyone this before …”

Before his death, Mel Moore made the decision to capture his life on paper. During the lengthy interviews about his childhood, military service, family and years of captivity in Vietnam, one couldn’t help but make certain assumptions about him. Today, some might call him “a man’s man.”

Mel wasn’t afraid to show emotion. As he spoke, he could cry or laugh at a story he was telling. At times his eyes held the pain of the stories being remembered. Other times, he developed a marvelous glint in his eyes as he smiled. His posture and complete being seemed to grow younger by the moment as his unbelievable tales of survival unfolded. And then, he uttered the words, “I’ve never told anyone this before …”

Mel Moore is survived by his wife Claudette “Chloe” Moore and three children, Michelle Moore (Alan Ogden) of Napa, CA; Melissa Moore of San Diego; and Leslie Phillips (Robert), also of San Diego. He is also survived by six grandchildren and one great grandson.

In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made “In Memory of Mel Moore,” to the Coronado Community Church, 639 H Ave, Coronado, CA 92118.

— Joe Ditler

Editor’s Note: Joe Ditler is an author, historian and frequent contributor to The Coronado Times. One of the services he provides is the capturing of one’s story, before it’s too late. In this case, he sat down with Mel Moore a year and a half ago, research at hand. For two hours, he recorded Mel sharing his life story, prompted by questions they had prepared with Mel’s family ahead of time. What this did, was to create a visual and oral legacy that will be appreciated for generations of his family to come. On the digital recording they hear his own voice, telling his very special story. They hear him laugh. They hear him cry. In Ditler’s words, “He left his family the most special gift in the world.” For more information, write [email protected].